Stylianos Kamperis, a BA student at the Institut Français de la Mode (IFM) in Paris, introduces his latest body of work, ‘Investigation, 2024’. Rejecting the pursuit of mere virality, Stylianos sees fashion as a medium for storytelling and emotional expression, aiming to provoke thought and connection through his art and hoping to spark a dialogue that transcends the conventional norms of the fashion industry.

hube: Could you share your experience of studying at the Institut Français de la Mode (IFM) in Paris? What motivated you to pursue the programme, and what are you most looking forward to gaining from your education there?

Stylianos Kamperis: When researching a BA course to further education in Fashion Design, I was drawn to taking a risk in moving away from home, leaving London, a city where I spent most of my life. IFM was an escape, a place in which students can learn together, but most importantly from one another, a place truly focused on preparing its students for the industry. The course places a strong emphasis on following prompts that allow for extensive experimentation with materials, forms and techniques, while also focusing on garment construction. I find IFM’s program unique due to its emphasis on pattern making and sewing, which is supported by tutors with years of experience in the fashion industry.

h: How does your approach to fashion design reflect an exploration of fundamental questions regarding the concept of life?

SK: To me, fashion, like all other art forms, is about communication. It’s a language. It’s a way of storytelling through the use of texture, form, colour and fit. When starting an investigation, philosophical and conceptual research take priority. I first look at what I want to say with my work, and then turn to philosophical concepts as my first concrete inspiration. My most recent investigation, for example, explores how we live in a time of extreme inequality, and although law creates a semblance of stability, the world is at war. While people die, others enjoy the luxuries of ‘lawful’ societies, fuelled by ideas of luxury and fulfilment. The investigation is supported by an Aristotelian concept regarding the pursuit of fulfilment in life through a metaphysical balance of law and chaos.

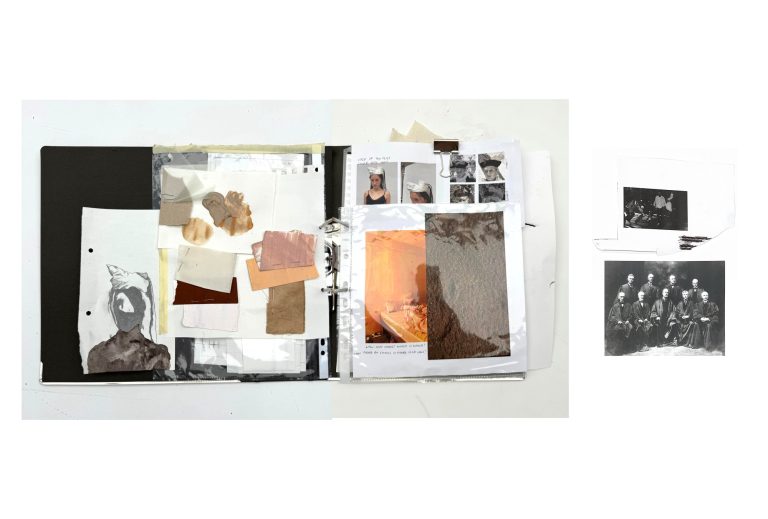

After identifying a concept that can support the overall message I wish to communicate, I turn to a wide approach for my research. Inspirational facets that connect to the main idea, often include cinematography, history and theatre. Research to me is the most important part of the process, it’s an endless exploration and interpretation of ideas. I refer to my bodies of work as investigations because to me that is what they are; I use fashion design as a medium to investigate different concepts and ideas that interest me, and that I hope my audience can relate and grow with. As investigations, my bodies of work never have an endpoint, they are open-ended questions that I hope to return to, reflect upon and evolve in the future.

h: How has your experience as a BA student at the Institut Français de la Mode influenced your creative process and the development of your artistic style?

SK: IFM has truly taught me the foundation necessary to create my own work and to construct garments. Learning how to pattern cut and sew has influenced my freedom of expression, which in turn has let me experiment with volumes, forms and restrictions. The school has enabled me to appreciate and recognise the importance of craftsmanship and meticulous work that goes into creating a garment. So much can be revealed from a garment by the way its patterns are drafted and by the way it is constructed. Through my most recent academic project, for example, I was pushed to work with the creation of a print, which in turn unlocked a new avenue of my artistic style that I am excited to develop further.

h: As a student, what challenges have you faced in balancing your academic responsibilities with your creative pursuits, and how have you overcome them?

SK: Being part of an intensive course at IFM, I initially struggled to balance the academic and creative standards I had set myself as a creative.

IFM has given me a deep understanding of the importance of craft and construction and the opportunity to push myself creatively through different design projects. Each project develops a new set of skills and requires students to follow a specified set of criteria. While this can at times feel limiting, it is a skill that ultimately needs to be mastered in order to work under a designer post-graduation.

That being said, I find that these years of education, especially art education, are the years to really go crazy and find your own creative identity. To do so, since the start of the course in September, I have constantly, and simultaneously my IFM projects, working on personal investigations. The duality between academic and personal creativity has been fulfilling, allowing me to grow as an artist and as a person. I have also, however, experienced some tough periods, where my drive has led to a sense of burnout, after many long days in the studio.