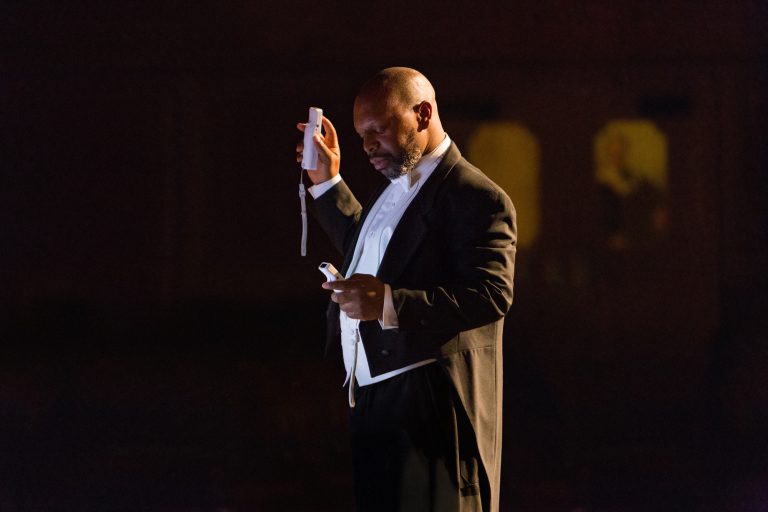

Photography by WHITNEY LEGGE courtesy of RASHAAD NEWSOME STUDIO

Being (the Digital Griot),artificial intelligence, 2019-current

Image courtesy of RASHAAD NEWSOME STUDIO

Rashaad Newsome is a boundary-breaking artist whose multidisciplinary practice defies categorisation. With a background spanning collage, sculpture, film and community organising, Newsome’s work challenges conventional narratives and explores the complexities of identity and technology. His global exhibitions and numerous awards attest to the profound impact of their art, which serves as a catalyst for social change and empowerment.

hube: Exploring themes of identity and cultural representation seems to be a recurring motif in your work. Could you share some key influences that have shaped your artistic journey in addressing these themes?

Rashaad Newsome: We all have our identities, such as race, class, gender, and sexual orientation, that coexist within us and influence the way we see and are seen by society. For example, as a Black, working class, gender non-conforming, Queer person, my experiences and the way I interact with the world are heavily influenced by all these identities. I cannot separate them or see social issues exclusively through one lens. The intersectionality of my lived experience is always with me. As art reflects life, it’s natural that it would be a part of the various conversations I’m having in my work.

A critical influence for me in understanding myself and how to talk about my work has been feminist scholar bell hooks. She often debated the direct link between representations in pop culture and how we live our lives: the over-sexualised woman that obeys the male fantasy, the Black male always being seen as the villain, the Queer man always being seen as weak, or the poor often deemed unfit for history. My work is a consistent effort to break free or reframe these types of structures that are persistently placed on us.

h: The ‘Shade Compositions’ series is a striking blend of performance, music, and digital art. What inspired the inception of this series, and what messages do you intend to convey to your audience through it?

RN: The work really came from a series of conversations I was having around 2004 regarding Black American vernacular, facial expressions, body language, gestures, and paralinguistics. I was thinking about how complex this shared collective communication method was but also how it was often framed as something ghetto or used by a person with a ‘low class’. Although this criticism was happening inside the Black community as well, the source engendering that self-critique came from white respectability politics. Could this language offer me something as an artist that might expand my practice and the performance art canon? Could it be an inspired attempt to reclaim those things that the world might teach you are lowly?

While developing the piece, I was also studying creative coding, which led me to build a custom video and audio recording and manipulation tool using video game hardware. The experience of creating that tool led me to explore the deep rabbit hole of Black folks and tech, and I’ve been on that train ever since.