In August 2022, Kisho Kurokawa Architect & Associates (KKAA) began to auction the rights to reconstruct the work of iconic Metabolist architecture, the Nakagin Capsule Tower in Tokyo. The rights are not only to build it in the physical world but also the virtual. As one of the few works realised by the postwar avant-garde Japanese modernist group Metabolism, the tower, completed in 1972, stirred a decade of debates over its preservation. In accordance with the Metabolist theory of constant renewal, the tower was intended to exist permanently through the replacement of 144 living unit capsules every 25 years, while the concrete cores remained. However, the capsules, which had deteriorated heavily over the past 50 years for a variety of reasons, were never replaced. The tower was carefully dismantled starting in April 2022, and subsequently, the restored capsule units will be shipped internationally to museums and collectors. As if to keep the tower living in perpetuity according to Metabolist ideals, KKAA partnered with the Japanese investment company Laetoli to sell the rights in OpenSea, a New York-based online non-fungible token (NFT) marketplace. Two NFTs were placed on the market, one to rebuild the tower physically anywhere in the world, and the other to build it in the metaverse. As a result, this news has provoked questions regarding distinctions between architecture in the physical and virtual worlds, as well as the new purposes that architecture in the metaverse may serve.

In his book Reality+, virtual world and the problems of philosophy (2022), David Chalmers, professor of philosophy and neural Science at New York University, argues that experiences in a virtual world can be as meaningful as those in the physical world. He posits that a virtual realism is genuine, and that “virtual reality is very much continuous with physical reality.” Despite the long history of the virtual being seen as ‘second-class reality,’ or as “an illusion or hallucination,” he asserts that, in fact, the physical is already continuous with the virtual. In an interview with Disegno journal this year and Fredrik Hellberg of Space Popular (a firm that designs not only physical buildings and installations but also examines the socio-political implications of virtual architecture), Chalmers says that if we talk about something that is virtual, it does not necessarily imply that there is an original that precedes it. For instance, to him, and to increasingly many others, an e-book is a genuine book. Similarly, architecture in the metaverse can be as genuine as architecture in the physical world. Recent occurrences in architecture and art have presented enthralling new possibilities in, as well as societal concerns associated with, the architecture of metaverse.

Photography by FILIPE MAGALHÃES and ANA LUISA SOARES

Photography by FILIPE MAGALHÃES and ANA LUISA SOARES

Bodies and buildings for liquid and electrons

Photography by FILIPE MAGALHÃES and ANA LUISA SOARES

In his 1997 essay ‘Tarzans in the Media Forest,’ Pritzker laureate Japanese architect Toyo Ito writes that the people of modern age are “provided with two types of body to match these two types of nature: the real body which is linked with the real world by the fluids flowing inside it, and a virtual body linked with the world by the flow of electrons.” He writes this while mobile phones are quickly transforming communication and socialization in Japan, particularly among teenagers. He observes that “their bodies crave the flow of electrons just as they need water and air.” Now over twenty years later, smartphones and touchscreens have become indispensable for teenagers, professionals, older adults, and younger children alike. Today, these two types of bodies appear to be increasingly melded together and unified, as evidenced by the ubiquity of other devices next to our skin, such as Fitbit and EarPods. An individual’s identity in the world is now defined as much, if not more, by the multiple profiles held through social media accounts and avatars.

Ito was one of the architects to see, over two decades ago, that the divisions between the two have quickly disappeared. He likens this blurring to the ways in which the people living along canals in Bangkok free themselves of distinctions between inside and outside, like amphibians. Broad terraces cantilever over the canal, and the stairs connect the canals to the living quarters, which are often open and visible to the public. Referencing Marshall McLuhan’s idea that clothing is as extension of human bodies, Ito further suggests that architecture will be and already is an extension of our bodies. This relates to the idea of the extended mind theorised by Andy Clark,professor of cognitive philosophy at the University of Essex, and David Chalmers in 1998, which asserts that the environment plays an active role in driving cognitive processes. Over the past twenty years, the radical idea that objects in the world, including smartphones, can become a part of the mind has become more intuitively acceptable. As human bodies now incorporate both fluids and electrons, architecture is designed for physical elements as well as electrons that flow through and project onto buildings.

Examining the reconstruction of Nakagin Capsule Tower

The rights to physically reconstruct the Nakagin Capsule Tower—with modifications to Kurokawa’s original design—presents a fascinating set of problems, enough to justify another essay entirely. In the context of this article, however, the NTFs used to reconstruct the tower in the virtual space have sparked timely discussions, interrogating and reimagining what it means to build in the metaverse. While the building was demolished for a variety of interrelated reasons—including the high price of the land on which the tower stands, and the lack of demand for solo-living in a tight quarter of a 10m2 capsule—one primary reason was that it had physically deteriorated due to poorly detailed connections and lack of maintenance by the building owner Nakagin. Water damage plagued the tower. In the metaverse, there is no need for showers or toilets, since electronic bodies do not possess bodily functions. Consequently, concerns for broken pipes or sewage leaks are eliminated. Those who lived in the capsules recall how their thin steel skin capsule provided very little protection from the heat and humidity in the summer and cold air in the winter. Besides the environmental discomfort, the hallways and the lobby, which had deteriorated and become deserted with only a few men in sight—and no women—was uncomfortable if not unsafe. The Nakagin Capsule Tower, designed for elite businessmen, excluded women from the outset and did not accommodate domestic functions. Could the virtual version resist the machismo ethos of Metabolism, and be more inclusive of women and domesticity?

In the physical world, good architecture is expected to provide its occupants with—at minimum—safety, comfort, and protection from the elements. Likewise, virtual buildings will be expected to protect occupants from threats and discomfort, but of different kinds. Chalmers writes about an incident dating back to 1993, in which one of the participants in a text-based virtual world felt sexually violated, and the offender was consequently eliminated from the community. Similar to the ways in which a street or a building in a city can be safe or unsafe, how can a virtual space be set up to be safe and ethical?

Photography by FILIPE MAGALHÃES and ANA LUISA SOARES

Changing virtual architecture

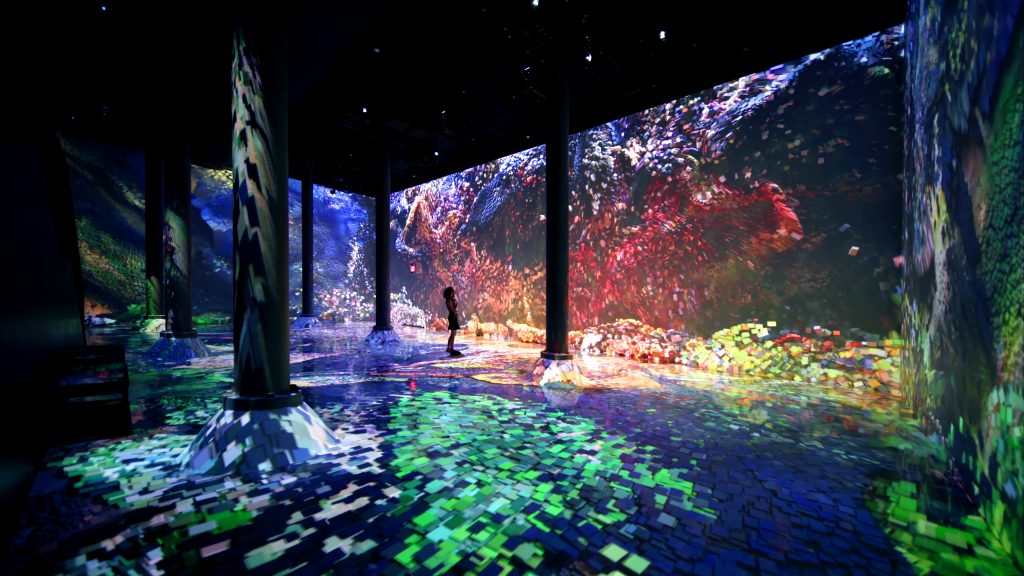

Courtesy of Refik Anadol Studio

Courtesy of Refik Anadol Studio

In the 1990s, architects understood digital architecture based on Gilles Deleuze’s sense of ‘virtual as potential.’ At the beginning of his book Animate Form (1999), architect and theorist Greg Lynn remarks that the word virtual was debased because it was often reduced to simulation. Virtual, on the other hand, according to Lynn, “refers to an abstract scheme that has the possibility of becoming actualised.” Lynn led the discourse in virtual architecture beginning in the 1990s, using animation software as a tool for design, rather than to simulate and visualize buildings that will ultimately be constructed physically. Much of today’s so-called architecture in the metaverse still remains a simulation of what is constructed with physical materials, often mirroring the parametric forms of their analogue buildings. Digital twins, or digital models built to simulate performance of a product or a system in the physical world, is rapidly becoming a norm. In one example, Red Wing Shoes announced in November 2022 that they have partnered with a metaverse developer and general contractors to build tiny houses both virtually and physically. The project BuilderTown enables virtual model of a tiny house to be viewed and discussed in Roblox, a digital gaming platform, before the contractors build it in wood, steel, and concrete. A notable difference between this and simply building a simulated model is the gaming community in which the model exists. A registered user creates an avatar and can not only build a tiny house in the multiplayer gaming environment, but also chat with and receive feedback from other avatars and tradespeople.

Such harnessing of virtual social interaction suggests significant potential for virtual community building, which can augment in-person interactions. While the profit-driven, capitalist platform of many projects in the metaverse is troubling, others are proposing community-based metaverse platforms focused on knowledge sharing and support, shunning monetary exchange and exploitation. A recent project by two architecture students, Hongjin Yang and Xiaorun Xu of the Harvard Graduate School of Design, proposed virtual therapy spaces for those afflicted with digital addiction; this suggests that addiction therapy can occur in a virtual environment, in augmentation with Zoom or an in-person session.

More recently, as virtual reality (VR) headsets have become more commonly available, VR is seen as something experienced through such glass screens. However, VR is increasingly becoming merged seamlessly with the physical; headsets, monitors, and tablets (like the one used for the popular augmented reality game, Pokémon Go) remain clumsy and get in the way of the sensual experience. In contrast, the work of artists such as Refik Anadol, who combines digital art with machine intelligence, enables experience of both the virtual and physical without headsets or devices. His work fuses art with architecture, turning building surfaces into seemingly moving, living spaces.

If we assume that humans will build and occupy both physical and virtual environments, architects will continue to respond to the concerns of structural soundness, sustainable material consumption, building maintenance, and social justice, among a host of other concerns around which architects are educated to design. In other words, hybrid or augmented architecture will continue to serve the purposes of Vitruvian principles of firmness, utility, and beauty. In addition, as architecture becomes more augmented and multivarious, new qualities will also emerge, one of which is a sense of beauty in the architecture of the metaverse.

Beauty in metaverse: Art as premonition for architecture

If the works of artists serve as any indicator of where architecture is headed in the future, as they have historically, it appears that our virtual and physical worlds are already merging, and the distinctions are becoming increasingly imperceptible. At the 2022 Venice Biennale art exhibition The Milk of Dreams, the pavilions appear to set the stage for artificial intelligence that makes data visible in the forms of flickering electric light. In the Japan Pavilion, the artist collective Dumb Type created a dark space in which a thin strip of flickering red light ran across the entire interior. Palm-sized mirrors on slender stands rotated at high speed, reflecting the laser that projected texts from an 1850s geography textbook, along with the sound of voices reading the text. Viewers became visually and aurally immersed in the space of a historical text.

Architecture critic Aaron Betsky writes that most NFTs have “an ethereal and evocative quality that belies what might happen if you tried to construct them.” Like the imagined worlds of novels, poems, or Surrealist painting that are equally—or more—meaningful and evocative than the lived experience, there may be beauty that can only exist in the virtual world. Perhaps there is beauty that can only be found virtually, but the new kind of beauty in art today exists at the intersections of the virtual and physical.

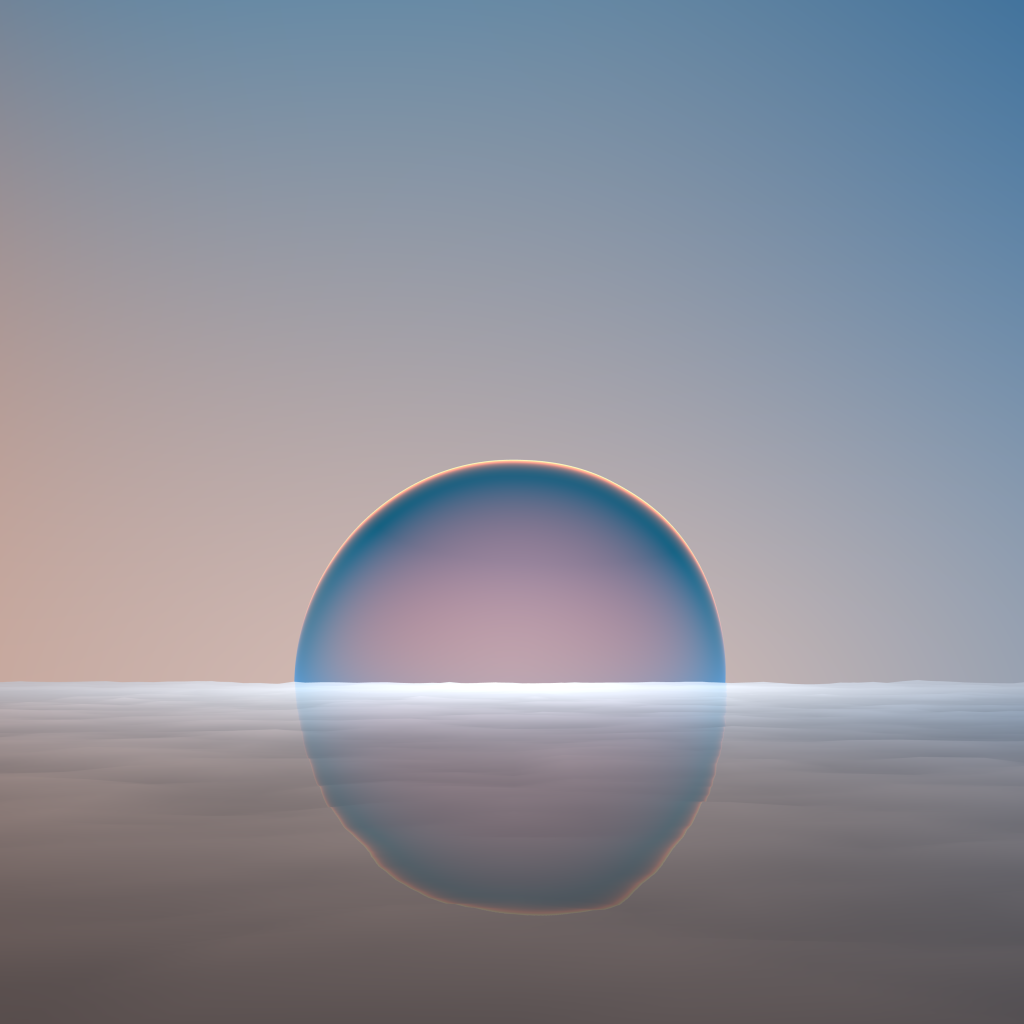

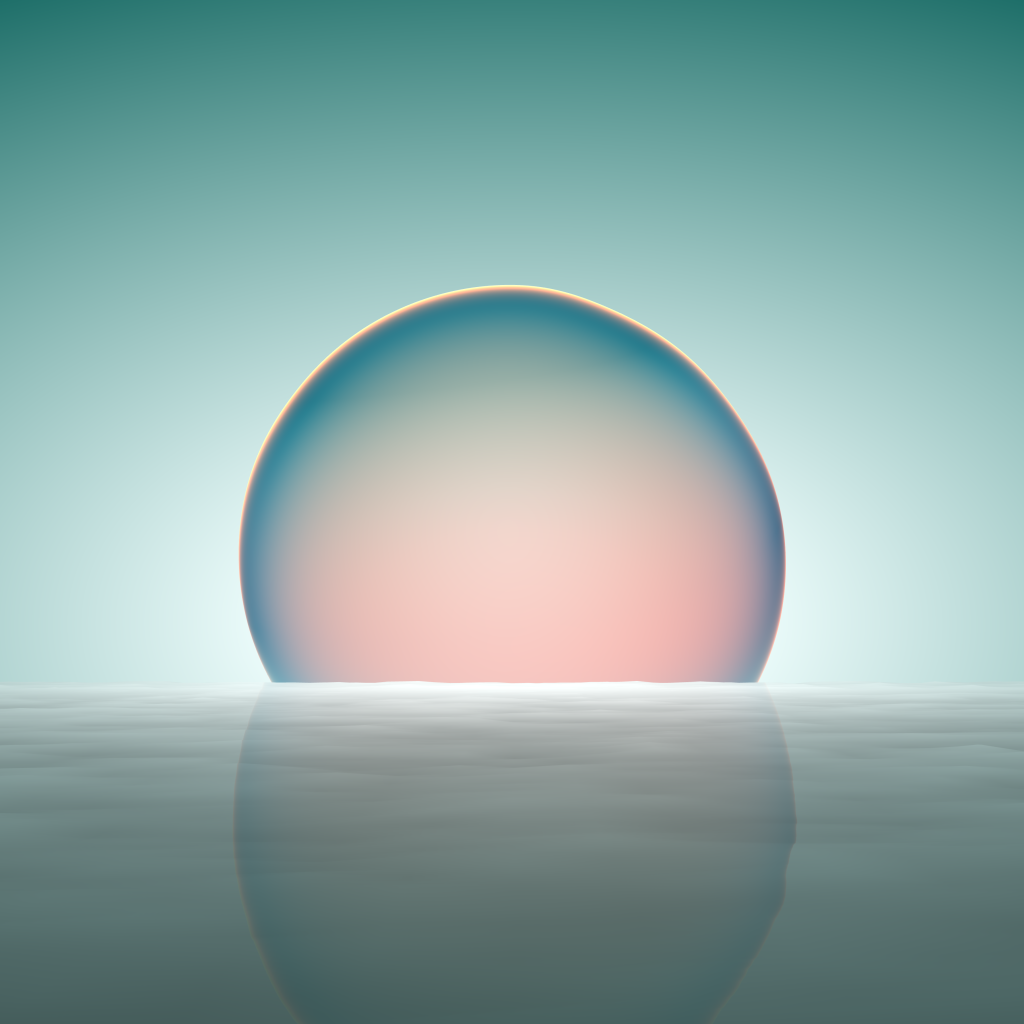

The London/Tokyo based artist duo A. A. Murakami create ephemera for Web 3.0. On the screen, droplet-like shapes appear to behave like fluid or gelatin, but the artists are not interested in a simulation of natural phenomena. In fact, in the physical space, the duo work with fog as a medium, and their NFTs are not a digital version of a so-called original. The digital work is as beguiling, if not more, than the physical. It suggests a new kind of nature that melds fluids and electrons—one that appears to have existed since the earth’s beginning, and at the same time found only in the future.

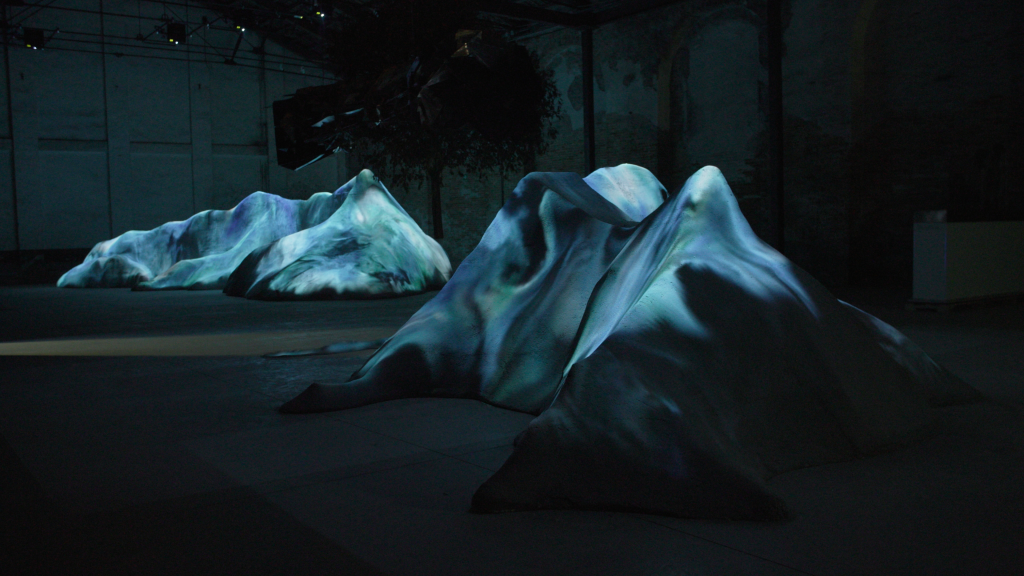

In the Venice Biennale’s China Pavilion exhibit META-SCAPE, artist Liu Jiayu creates Streaming Stillness, a 21-meter mountainous terrain, onto which real-time rendering of 10,000 Chinese ink-wash landscape paintings, processed and trained using artificial intelligence and machine learning, is projected onto terrain surfaces according to China’s topographic data. The streaming motion graphic in muted green and grey tones make the watery brush strokes of the paintings softly recognizable yet not obvious. The artwork “comes from the real world yet doesn’t exist in it. Instead, it’s a natural prototype existing beyond human experience and reaches transcendence,” says Jiayu. This hybrid work combines a physical sculpture with digital visualization that seems to flow like liquid over the terrain. Beauty of architecture in the metaverse may similarly be situated at the juncture of physical and digital, in the uncanny sensation not found in either the solely physical or the virtual world, but one in which sensations become more alive when the two meld.

If the Nakagin Capsule Tower were to be built virtually, one would hope for it to be as visionary as it was in 1972, and not be a nostalgic replica. There is a compelling prospect for the tower to live in perpetuity through an ongoing cycle of life and death, as the Ise Grand Shrine has for over 2,000 years through cyclical rebuilding, adapted to the various changes in society. In the virtual reconstruction of the tower—and more broadly in the architecture of the metaverse—instead of replicating the appearance of concrete and steel, its materiality could suggest a substance that is alive, fluid, and somehow electric, designed for bodies built for both fluids and electrons.

Venice Art Biennale, 2022

Venice Art Biennale, 2022

This is an excerpt from an article published in the first issue of hube magazine. For the full experience, you can buy a copy here.