Born in 1960 in Hertfordshire, England, Simon Critchley is an English philosopher and professor of philosophy at New York’s New School for Social Research. A public intellectual, he has written widely, encompassing topics including David Bowie, religion, politics, and football, though he is best known for his books The Ethics of Deconstruction (1999), examining Derrida’s ethics, and Infinitely Demanding (2007), a treatise on the relationship between philosophy and disappointment. His last book, Bald (2021), was a collection of his essays from ‘The Stone,’ a column he wrote for the New York Times that doubled-up as a forum for thinkers and philosophers to discuss issues ranging from pop culture to politics. In this interview, Mr. Critchely expands his relationship with time, reality, and inauthenticity, a concept that he argues is worthy of greater celebration than the idea of realness itself.

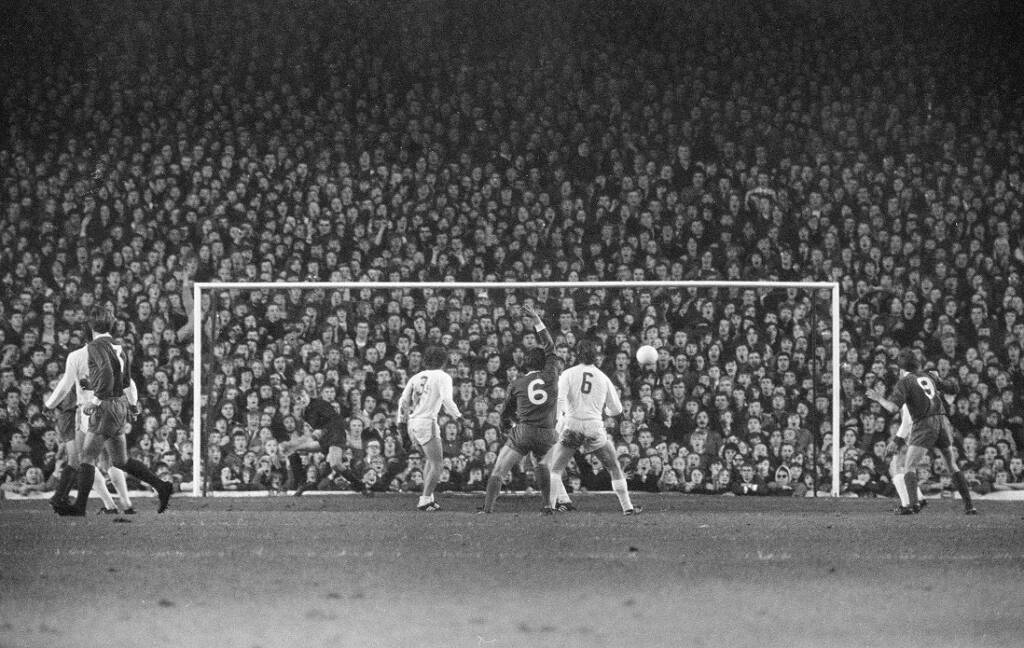

Inter-Cities Fairs Cup Quarter-final, 1st Leg match at Anfield, 1971

© MEALEY, courtesy of MIRRORPIX

Inter-Cities Fairs Cup Quarter-final, 1st Leg match at Anfield, 1971

© MEALEY, courtesy of MIRRORPIX

hube: To us, it seems that philosophy often denies its own practicality. This denial gives philosophers necessary freedom while protecting them and their theories and statements from too much public attention. Was your path to philosophy shaped by a desire for such freedom of thought?

Simon Critchley: Well, I disagree with the premise in which denial gives philosophers the necessary freedom while protecting them or their theories and statements. I mean, philosophy begins, arguably, with Socrates, and he was executed by the city of Athens for the charge of questioning the gods, corruption of the youth. So philosophers have been a subject of quite a lot of persecution over the millenia. To that extent, there is a greater deal of risk involved than what people usually imagine. It’s not as if it’s some otherworldly activity divorced from social life. It’s an intervention, a questioning which is practical and which can come with a real cost. The first thing I’d say is that philosophy kills or it can kill. There’s a whole history of philosophers who’ve been imprisoned, executed, excommunicated, and so on and so forth, for their views. So that freedom of thought is something which is won at a certain cost, for sure.

h: Today’s ethics, morals, and laws are derived from thousands of years of philosophical contemplation. How does the transition from theory to practice work? Where does philosophy end?

SC: Well, it doesn’t end. And hopefully it won’t ever end, and although it’s fragile, it does depend on conditions of a certain freedom. Philosophy is an institutional activity and academic activity is fragile and can be threatened and menaced, no doubt about that. Again, I disagree with the question [laughs]. It’s not that ethics, morals, and laws are derived from thousands of years of philosophical contemplation. I don’t think they are anyway. I think ethics, morals—by which I understand just the customs of different cultures across thousands of years—are not derived from philosophical contemplation. They’re derived from the inheritance, the accumulation of ways of life. What they call in France les mœurs, morals, practices.

I mean, philosophy could be seen as something which questions those practices. But ethics, morals, and laws, in many ways, are derived from actual human social interaction over decades, centuries and millennia; and so, to that extent, it’s the same question about the practicality of philosophy. From the very beginning of philosophy with the ancient Greeks, there’s a very clear sense that philosophy is somehow otherworldly because it doesn’t subscribe to the customs, ethics, and morals of the particular society in which people live. It questions them. The philosopher is a kind of otherworldly figure in a way, who doesn’t seem to be constrained by the laws of the city, the morals of the city. But it’s a practice, an activity, something that is done; and to that extent, philosophy is always practical. But it’s not as if there’s some theories that one has to apply. Philosophy is a practice of intervention in a certain society which very ultimately calls into question the ethics or laws that govern the society.

h: Freedom allows philosophy to build relationships with reality, even though sometimes it can be paradoxical, ranging from confession to denial. What is your relationship with reality?

SC: My relationship with reality is pretty good. It’s very ordinary. Philosophers are genuinely puzzled by things. In many ways, the philosophical ‘mood’—if there’s a mood that gets people into philosophy—you could say it’s a puzzlement, a perplexity about the nature of things, but not necessarily a knowledge of how those things are. Freedom allows philosophy to build relationships with reality, but that depends where you are and what you’re thinking. So in response to the question, my relationship to reality is the same as yours; and for me, I’m still deeply puzzled by it.

h: Many people perceive contemporary art as a world of ideas. The metaphorical, the meaningful, and the universal. Do you feel any sort of competition between art and philosophy?

SC: Going back to our friends the ancient Greeks, the most influential philosophical text is Plato’s Republic, in Greek Politeia, which is just about the city and the nature of the city. Towards the end of the book, there is what Socrates calls an ancient quarrel between philosophy and poetry. Ancient Greece in the fifth century BC is rooted in a culture where poetry, particularly Homer and things like ancient tragedy, really were the dominant governing media of the day. To that extent, the question Plato raises is whether art is true or not, or whether it’s just making things up. And his rather extreme view is that art is an imitation of an imitation. It’s a world of illusion. And if you’re interested in reality, then you should commit yourself to philosophy rather than poetry or art. So in Antiquity there is a competition between art and philosophy, certainly. But I think, in relation to where we are now, in the last few hundred years, there’s been much more of, not exactly a marriage between art and philosophy, but a sense in the deep philosophical questions which philosophy is trying to answer, [and which] are perhaps better addressed through art, however the form.

We could talk about contemporary art, too, and what that really means. These would be philosophical questions. When does contemporary art become contemporary art? There’s some kind of implicit understanding that there’s something called modern art, which covers some point in the 20th century. And then there’s contemporary art. But contemporary art is like a product, a social one, especially in the 1970s and 1980s. Then, it begins to be kind of institutionalised. We begin to see the opening of museums of contemporary art. Next, universities develop programs in contemporary art, and there’s a market in contemporary art, and so on and so forth. I think philosophy would be in the business of raising just questions about that. Questions about the legitimacy of the whole activity. But there is an ancient rivalry between art and philosophy, no doubt about it.