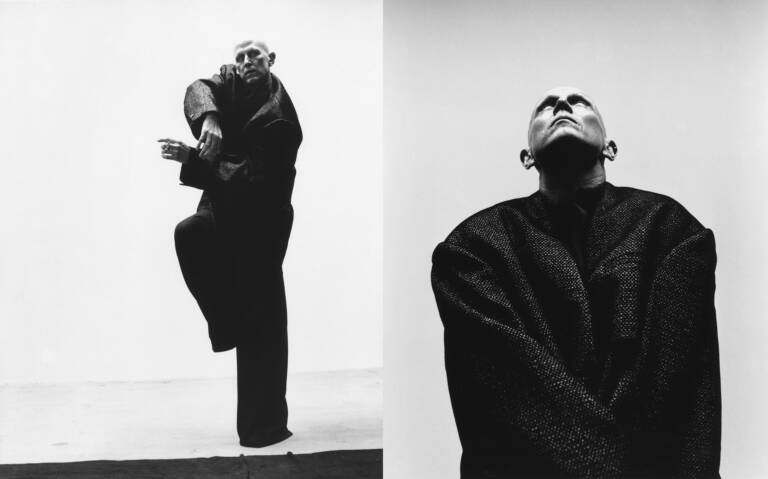

Wayne McGregor is one of the most renowned names in contemporary dance—and one of its most radical thinkers. Over the past three decades, the London-based polymath has approached choreography as a form of enquiry: a means of understanding how we perceive, process, and inhabit the world. As McGregor argues, movement isn’t a result or product of thought, it actively participates in the act of thinking.

His expansive contributions to the field have earned him a CBE and a knighthood; he is Resident Choreographer at The Royal Ballet—the first from a contemporary background to hold the position—and has served as Artistic Director of the Venice Dance Biennale since 2021. McGregor’s interest in physical intelligence and new technology has taken his work far beyond the stage.

His numerous ventures include collaborations with cognitive scientists and psychologists, developing choreographic AI tools, and a research fellowship at the University of Cambridge’s Department of Experimental Psychology. His forthcoming exhibition, Infinite Bodies, marks a rare institutional moment. Staged at Somerset House on the occasion of its 25th anniversary, it offers insight into 30 years of groundbreaking choreographic work. Ahead of its opening, we sat down with McGregor to discuss the show and the complex, evolving nature of his practice.

Caroline Roux: First of all, let’s talk about the run-up to Infinite Bodies which opens at the end of October in London. It will be the largest exhibition that Somerset House has ever put on. Is it your largest exhibition too?

Wayne McGregor: I’ve only done one exhibition before, at the Wellcome Collection, called Thinking with the Body. That was in 2013, and it was very specific. It was connected to the interdisciplinary research we had done with social and cognitive scientists. It’s very unusual for a choreographer to have an exhibition as broad as the one at Somerset House.

Even in the history of choreographic practice, exhibitions tend to be around scenography or costume design, the actual things and objects that are part of performance, and maybe photography and film. It’s unusual to have one that explores choreographic practice beyond the stage.

CR: How are you moving the goalposts?

WM: I’m not sure I am! I think we’re just collecting together all the work that exists or has existed outside the stage work, and putting it all together and saying, you know, when you bring all of these works together, you’re getting a sense of physical intelligence that perhaps you wouldn’t get when you’re watching the stage works. I think when you collect them together, you also get to feel a more philosophical understanding of what the deeper enquiry is in choreographic practice. That’s not to minimise the significance of the stage work, but choreographic thinking and choreographic practice pervades every area of living. We are all doing it all of the time. I’m sure a lot of people hear the word “choreography” and they think about Debbie Allen—who played the dance teacher in Fame—dance steps, and putting on a show! But there have always been practitioners in the history of choreography who have recalibrated that. Think of postmodern Americans, like Trisha Brown or William Forsyth. So, we thought it would be fantastic to have an exhibition which explores physical thinking, where people will be surprised about what is choreographic, and what the attributes of choreography are.

It’s been interesting trying to select what to show—we’ve done so much experimental work beyond the stage—so we’ve tried to make a dramaturgy that runs through the exhibition that will help to elucidate very specific areas of choreographic thinking. Hopefully the audience will think, “I didn’t see that as choreography, but now I do.”

CR: Will it be a very aesthetic experience, or maybe something more phenomenological?

WM: Visitors will have time to stay with something longer than they would in a stage per- formance. When it’s in a theatre, I decide how long you get to stay with an idea. In this context, you have all the time you want. You can read about an exhibit, or just experience it. You can decide to go through it somatically, to sense how the body feels, but equally there will be a lot of objects in there. It touches all the central ideas around choreographic intelligence that we’ve been kind of investigating with people outside of the usual collaborators.

CR: Can you describe what we might expect to find?

WM: There will be a range of performative installations, some are made with lights and bodies, some are completely digital, some use the latest AI systems that recalibrate performance. The public will have access to AI tools that allow them to act, for a moment, as the choreographer and to use their bodies to express physical phrases. There will be live dance at certain points, everything will in some way generate empathy, and it will be fun.

There are two completely new works, including one that I made with Industrial Light & Magic, George Lucas’ company. The idea was how do you make an infinite dance, and what does that even look like?

CR: And so we’ll still be looking at human bodies?

WM: The exhibition starts with the question: what is a dance? Is it only about a live human body? What else could express space, time, motion? On The Other Earth, the other major new work takes the latest technology to give a small, intimate group of audience members a dance experience that they have never had before. It’s the world’s first 3D 360 degree environment.