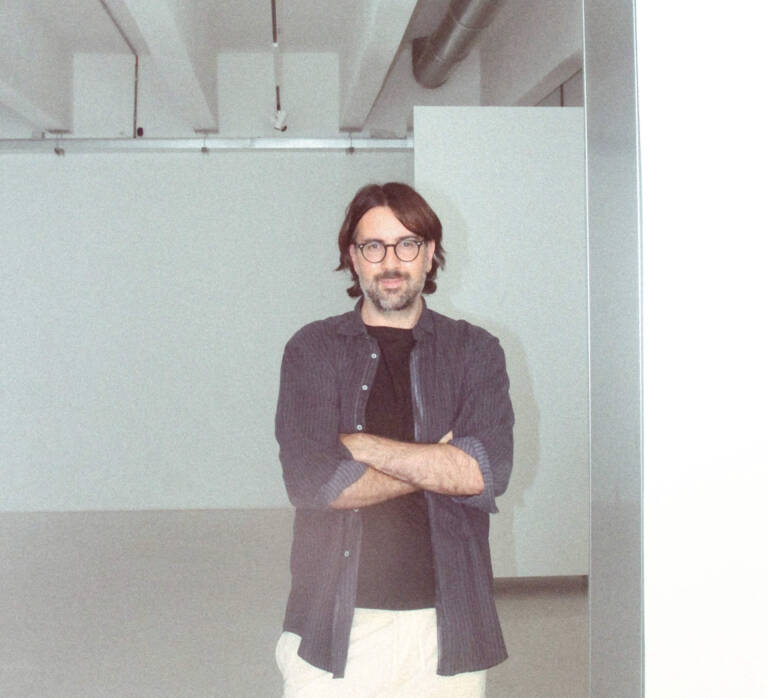

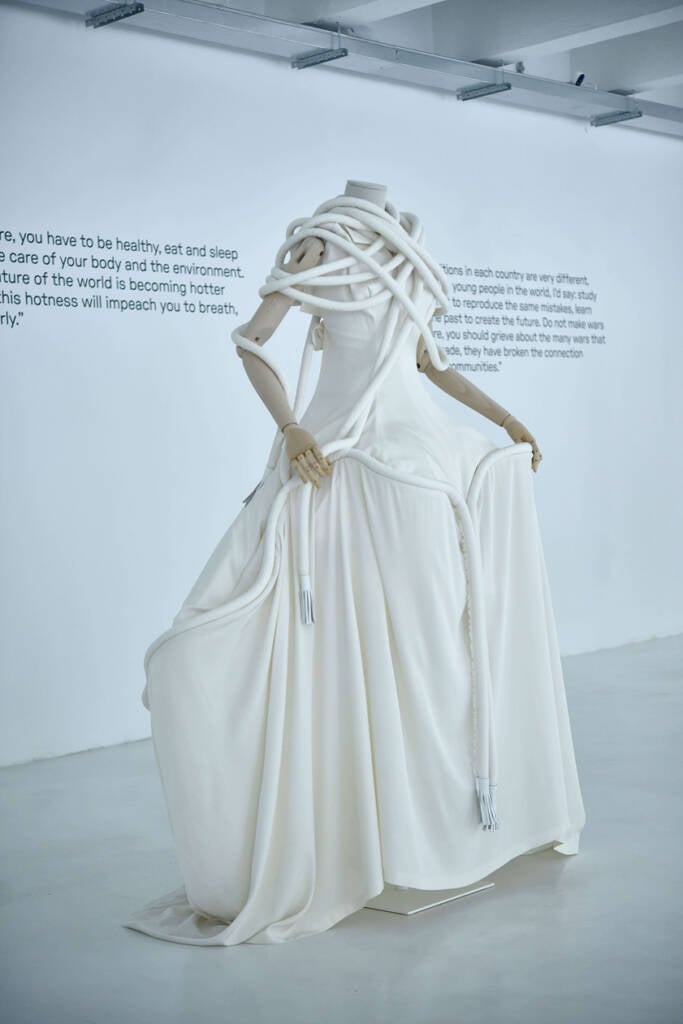

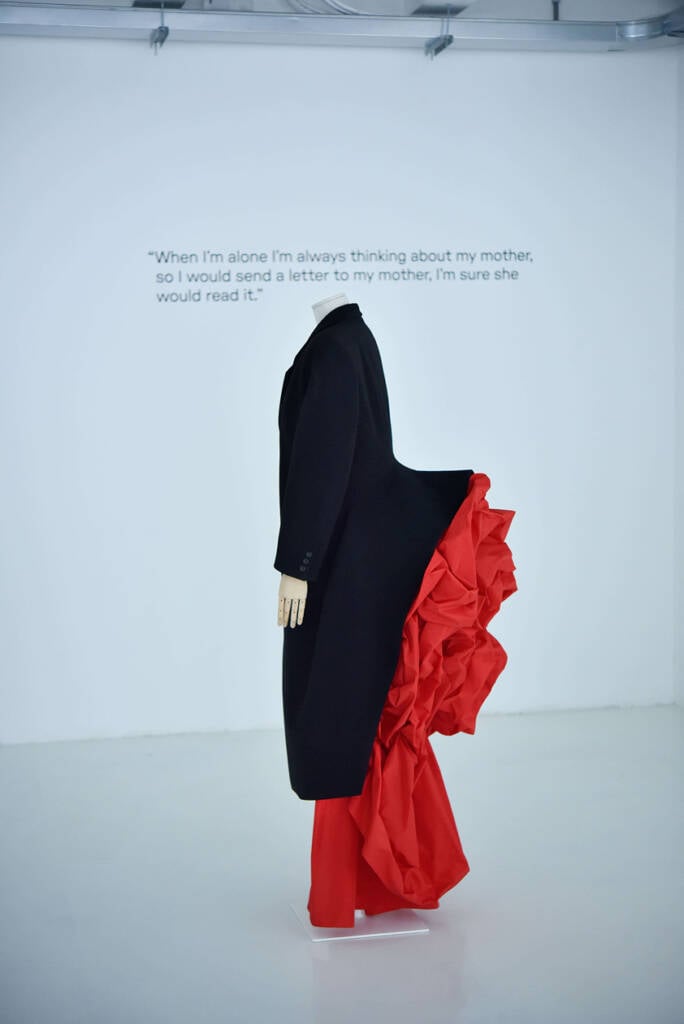

Alessio de’Navasques is a curator, writer, and researcher whose work reimagines fashion curation as a form of cultural expression—one that reflects both history and the present. As Curator of Cultural Programs at 10 Corso Como in Milan, he has organized major exhibitions such as Yohji Yamamoto: Letter to the Future, Andrea Branzi: Civilisations Without Jewels Have Never Existed, and Glen Luchford: Atlas. Known for bridging fashion with art, architecture, and critical theory, de’Navasques has introduced innovative approaches to how fashion can be exhibited and interpreted.

In 2012, he founded A.I.–Artisanal Intelligence, a platform dedicated to craftsmanship, heritage, and innovation in Italian fashion, supported by AltaRoma and leading institutions across Europe. A lecturer in Fashion Archives at Sapienza University of Rome, he has also contributed to Vogue, i-D, Artribune, and DUST Magazine. His ongoing work continues to shape how we understand fashion today—not as an isolated discipline, but as a living mirror of the world around us.

hube: You grew up in Puglia, a region that has undergone remarkable cultural transformation in recent years. How did the landscape, traditions, and shifting identity of that place shape your visual and curatorial instincts?

Alessio de’Navasques: Talking about Puglia, it’s a land full of inspiration. From a curatorial perspective, however, I don’t have many references there because my vision has always been international. I left Puglia a long time ago, and since my father is from Rome, I’ve always felt a stronger connection to that city, where I have been living for more than twenty years. Rome is endlessly inspiring—a place where the past is constantly reinvented in the present. In that sense, my projects are shaped more by Rome than by Puglia.

Puglia is undergoing a major transformation, yet culturally it still feels underdeveloped. The contemporary scene is trying to emerge but hasn’t quite taken shape yet—though I hope it will. There are some interesting independent spaces, but institutional support is almost entirely absent. The region is rich in cultural heritage, but when it comes to the contemporary, it’s still lacking.

One thing that is part of my DNA, however, is the connection between craft and territory. That’s something I began exploring early in my career when I founded A.I.–Artisanal Intelligence. The idea of heritage—the intangible heritage embodied in craftsmanship—is something I learned to value deeply. It’s tied to the land, to tradition, to the techniques and artisanal practices that have been passed down from generation to generation and carried into the present. It’s something rooted in the spirit of the territory—part of me.

h: Your path into the cultural field spans fashion, curation, research, and education. Was there a defining moment or influence that clarified your direction? What helped you understand your voice as a curator and cultural mediator?

ADN: All those aspects are components of one vision: education. It’s something that comes when you research; it’s beautiful to share with students, and you can learn a lot from them. Education is always part of sharing and research, there is a lot to do in Italy in terms of fashion curation. There are many archives, and fashion studies still feel pretty new. In terms of research, it’s only in the last 30 or 40 years that this field of study has developed.

In fashion studies, you have a very academic field and some independent scenes, and sometimes those two aspects are not integrated. I’m trying in my projects to integrate both visions—reading and activating archives through contemporary questions.

It’s about understanding how we can talk about fashion in a different way, finding a voice that is independent and can reach a larger audience, because sometimes fashion studies are enclosed in the small island of academia, with little connection to the contemporary.

I’m a part of a generation between those who started this kind of work, when there were no fashion studies, and the new generation that comes from them. Most scholars came from anthropology, sociology, history, or art history. I’m an architect. There was a desire to bring out all this knowledge and culture about fashion. My process is around intuition; it’s not logical or classical.

Photography by GILDA & BODHA

Photography by GILDA & BODHA

Photography by GILDA & BODHA

Photography by GILDA & BODHA

Photography by CINZIA CAPPARELLI