In photographer Nat Faulkner’s practice, the image moves beyond representation and into the obscure. Working with liquid iodine and the materiality of the photographic surface, he creates visuals that unfold across the gaze like illuminated manuscripts: worlds blurred by vivid, contrasting hues. A fixture at Soho’s Brunette Coleman, Faulkner’s work travels by word of mouth across London, known for its striking subtlety. Performing his process as a kind of ritual in the dark, he translates a background in sculpture into the language of contemporary photography, experimenting with unconventional printing techniques that further transform the materiality of his images. In this interview with hube, he reflects on the natural evolution of his practice, the beauty of light leaks, and the magic in science.

hube: Much of your past work evokes an “out-of-body” sensation. How do you navigate the tension between working through such physical, analogue gestures and trying to grasp something that resists material form?

Nathaniel Faulkner: My aim has always been to approach my work as a process of uncovering, creating the conditions for it to emerge rather than willing it into being, an autonomy that the darkroom itself cultivates. Working with analogue photographic processes means regulating and controlling certain parameters; in the production of an image, I will choreograph and rehearse that process before finally performing it in the dark. There is a lot of ritual involved, both mentally and physically. When in the dark, at first, it is difficult to move around and my eyes will strain to adjust to the low light, but by the end of the day, the space feels natural and as familiar as daylight. The work becomes a by-product of that collaboration, passively shaped by the studio-as-machine.

The tension between the physical, analogue gestures and the immaterial qualities of my practice is inherent to the medium and its conditions, I only choose to amplify them. Photographs emerge from an environment of sensory deprivation, and the residue of that clings to the work.

h: Distortion runs across your practice, through collage, scale, and printing techniques. Would you say you’re constructing an alternate reality? What kind of “truth” do you think the viewer encounters in these shifted perspectives?

NF: Distortion through enlargement is an interesting notion. In photography, transformations of scale occur constantly, the scene is condensed onto a negative, then enlarged again in print. This bow-tie shape is an apt symbol, what happens during those in-between stages of transformation? Distortion suggests a warping of reality, I’m more interested in magnifying it. I might distill and preserve a solution, suspend silver on glass or copper, or enlarge an image sixtyfold, revealing the film grain and fixing it among the studio dust that drifted into the enlarger. When I use a subject, material, or image, I try to inflate it like a balloon, stretching its information to reveal the DNA.

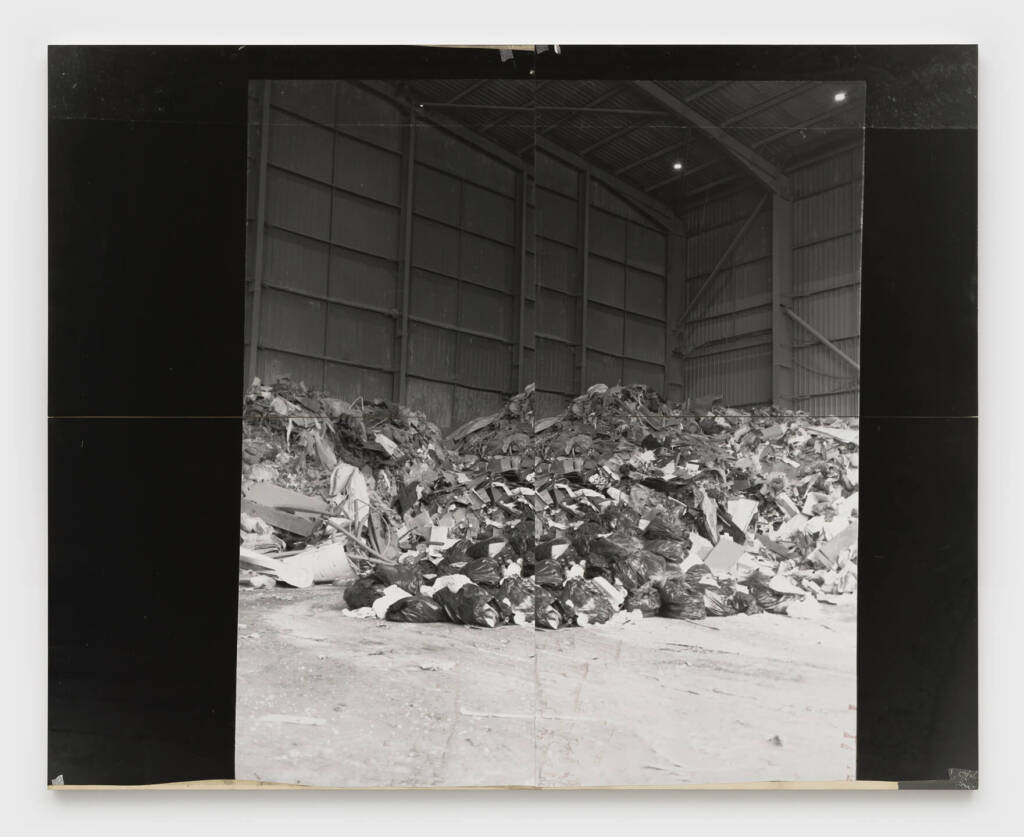

Untitled (Mercury Way, II), 2025

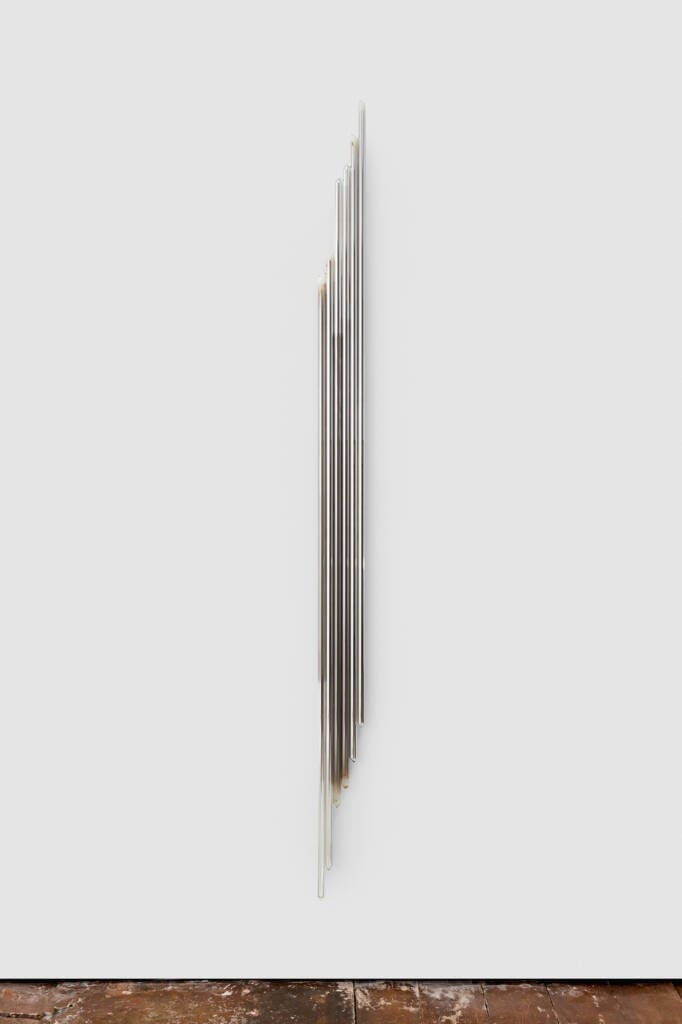

Ampoule IIIIII (Silver), 2024

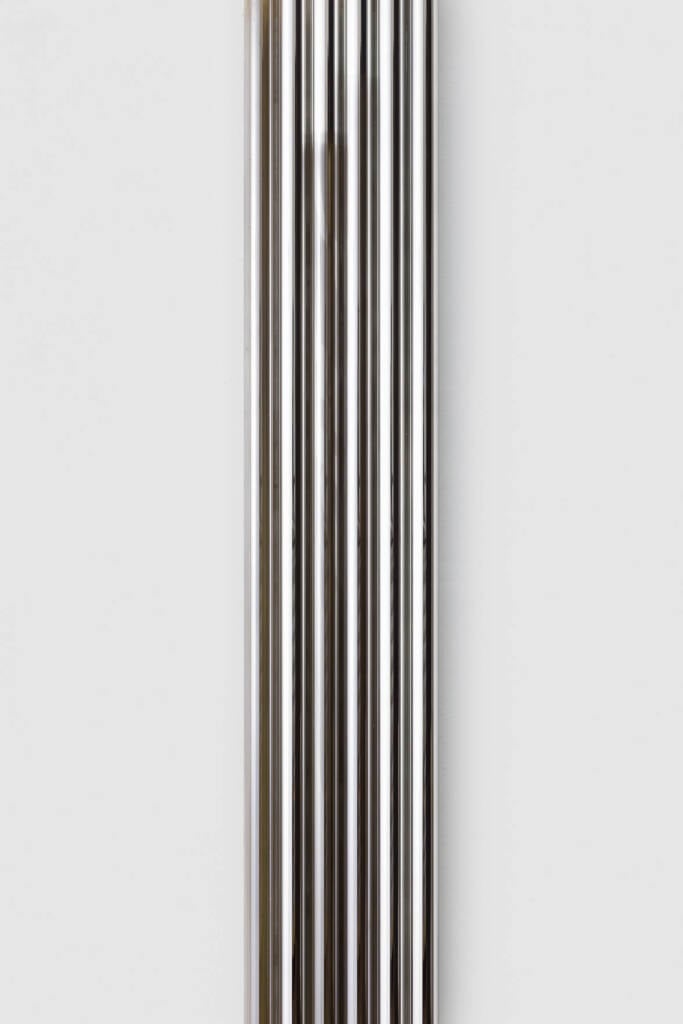

Ampoule IIIIII (Silver) (detail), 2024

Ampoule II (Positive_Negative) (detail), 2024