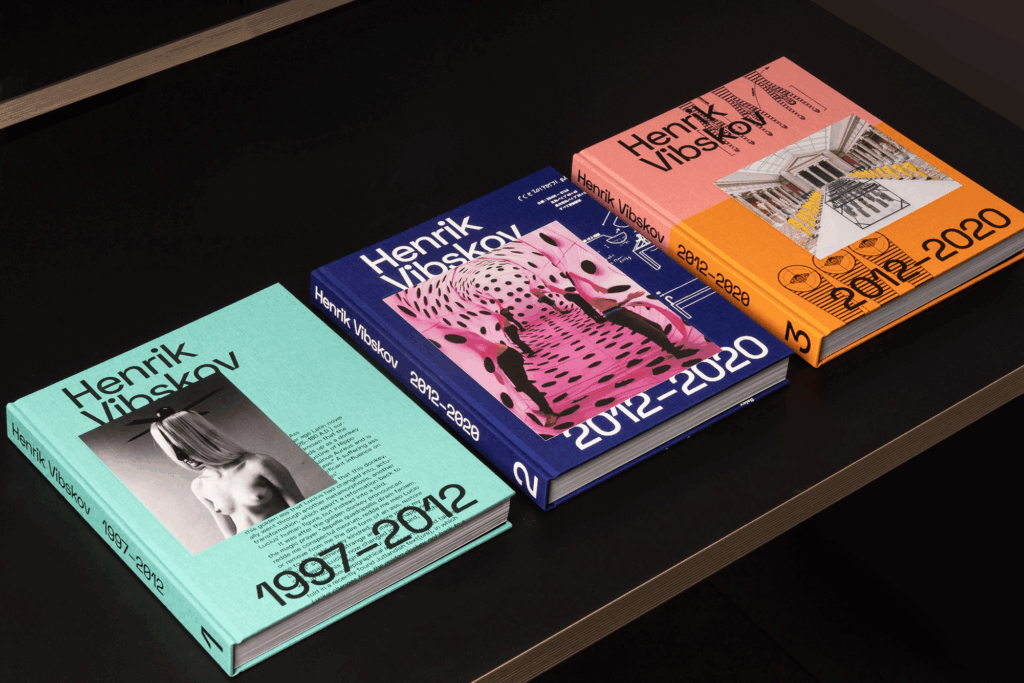

When one thinks of Scandinavian fashion, the mind doesn’t usually jump to bold colors and eccentric prints. Yet Danish designer Henrik Vibskov has spent the last two decades rewriting that narrative. His work moves fluidly between fashion, music, performance, and installation, creating a world built on rhythm, color, and play. Through garments, objects, and immersive spaces, Vibskov transforms the ordinary into the surreal, crafting a universe where experimentation is the rule.

In this interview with hube, the artist reflects on his ongoing exploration of form and material, his current obsession with How to Cook a Bear, his idea for a “speed dating” dream dinner party, and what it means to sustain curiosity after twenty-five years in the industry.

hube: You’ve been part of the fashion and art world for over a decade now. Looking back, what has changed in the way you approach creativity, and what still inspires you to keep going?

Henrik Vibskov: It’s actually been nearly 25 years since I graduated from Central Saint Martins. What’s changed most is my relationship with form and material. Back then it was all about expression, being wild with shape, form, and structure. But over time, everything shifted toward material, especially from an environmental point of view. What kind of material is it? How can I create less waste? How can I shape something differently? That’s been a big game changer.

What keeps me going is the variety. I’m constantly switching between projects like fashion, ballet, and installations, so I’m never just doing the same red cardigan over and over. That keeps the passion alive.

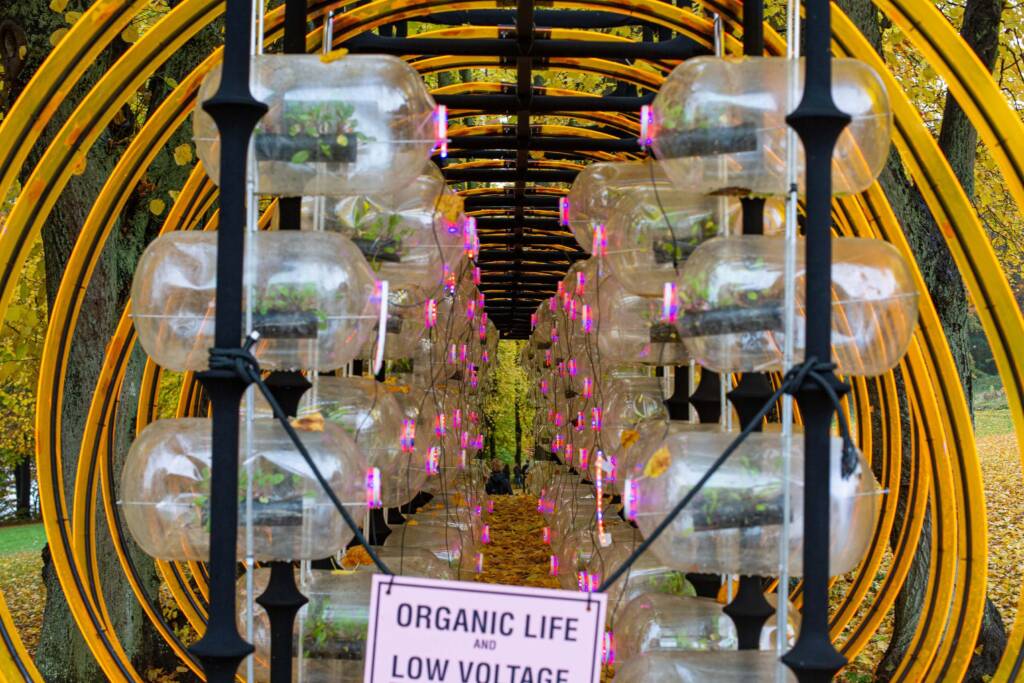

h: Patterns, structure, and visual logic are central to your DNA, yet you now also create immersive installations. How does your mind navigate between the tangible discipline of garment-making and the expansive freedom of spatial art?

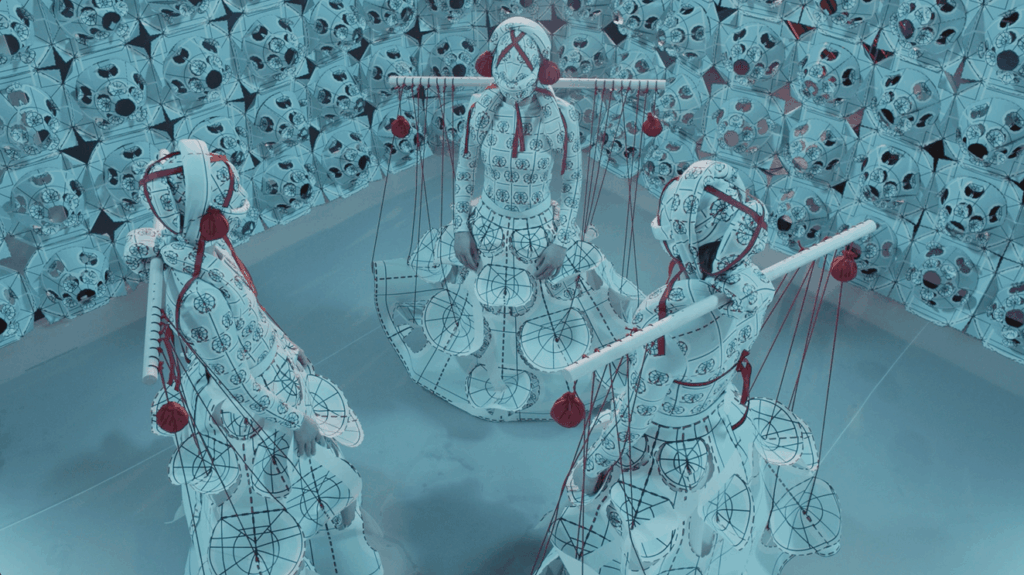

HV: I was at the Royal Academy yesterday for a talk about how runway shows today often come with a set or conceptual layer, it’s not just straight walks anymore. I spend a lot of time creating installations and narratives that expand beyond the clothing itself. It gives the work more depth and longevity. Instead of a static lookbook, which can feel flat, storytelling makes the image last. It gives it value beyond the moment.

h: You studied at Central Saint Martins, a building that acts as a crucible for creativity. How did that time shape the way you think today? Does London still feed your imagination, or has it become more of a chapter you reflect on?

HV: What I took from that time was the constant questioning. Why am I doing this? Being critical of storytelling and concept. I still work like that. I always ask myself, why is it red? Why this shape? Why this texture? That mindset came from having to defend your work during critiques, you needed to explain and justify every decision. I think that way of thinking never left me.

h: When it comes to patterns and prints, where do you primarily draw inspiration from?

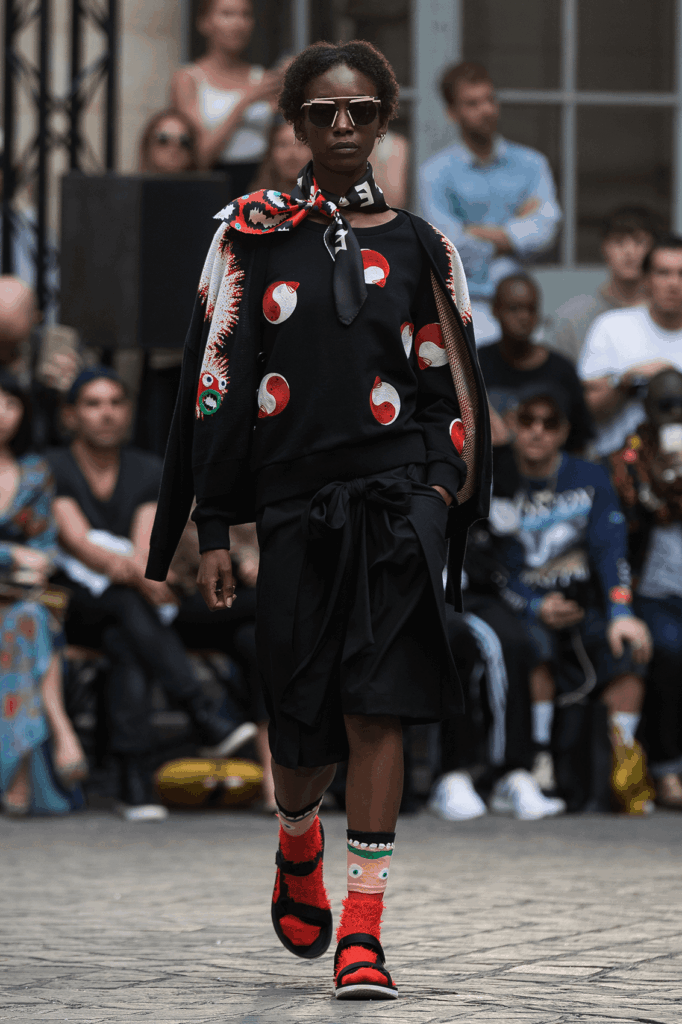

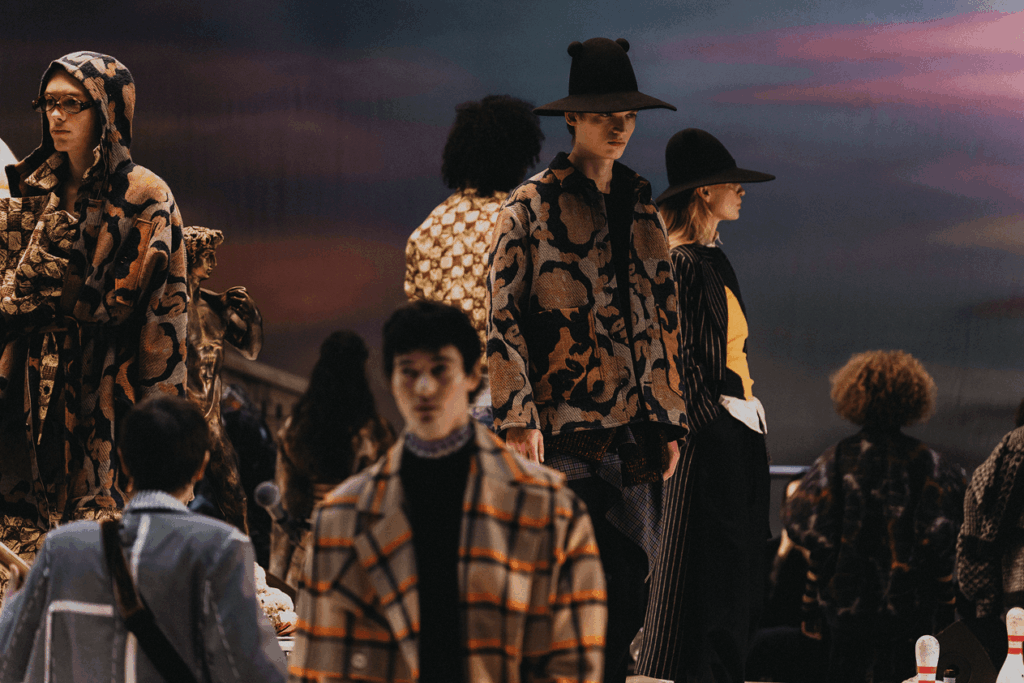

HV: My concepts usually come from observing how we live, our habits, routines, and weird rituals. It could be sports, sleep patterns, or protection. My last show, for instance, explored how we protect our values. Does a building hold more value than a human being? I looked at flight cases for instruments, banks, and amulets, objects that safeguard something precious, whether physical or spiritual.

h: Music was a formative part of your early world from Luksus and Hess Is More to Mountain Yorokobu. How does sound influence your life and work today? If you could step into any band tomorrow, who would it be and why?

HV: Music shaped everything I do, emotionally and collaboratively. When you’re in a band, you’re constantly aware of what everyone else is doing. You respond, you adapt, like kneading dough together. That awareness carried into my design process.

h: Is there such a thing as an “average” day in your life in Denmark? If so, what rhythms or rituals structure your creative practice?

HV: I try to keep some rhythm, coffee, bicycle to the studio, the usual. But creatively, I make time for daily rituals: half an hour of drums, half an hour of drawing, half an hour of reading. It’s easy to skip, but those small practices are crucial to maintaining flow.

h: Is there a book that you’re reading at the moment?

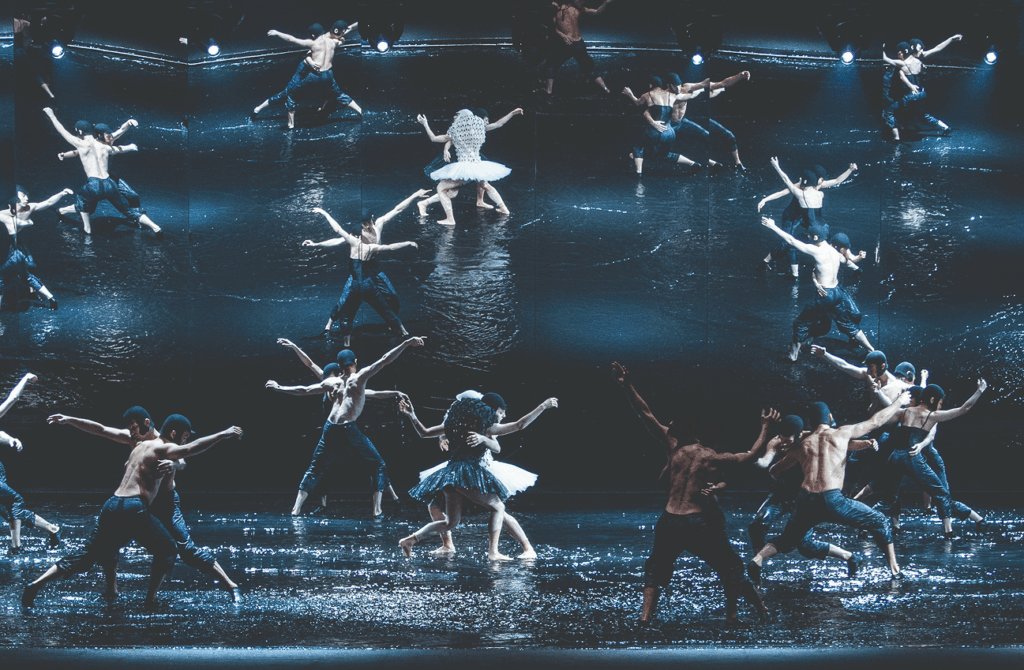

HV: A book called How to Cook a Bear by Mikael Niemi. I’m working on a ballet set above the Arctic Circle, about Sámi culture, and this book captures a similar atmosphere. It’s about a series of murders in the north, quite dark, but beautifully written.

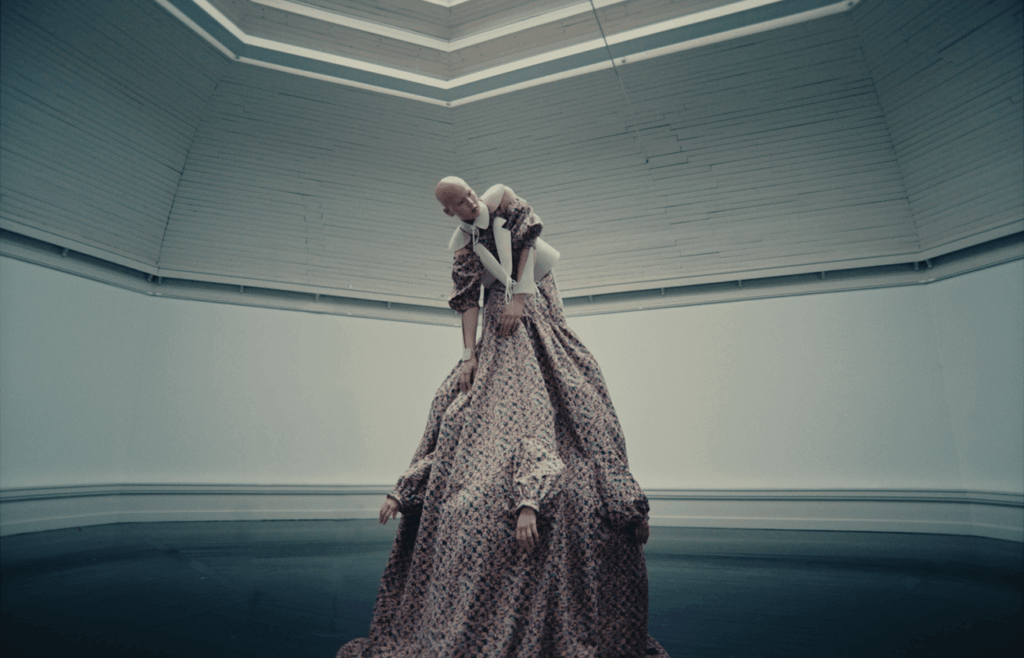

h: How does designing costumes and sets for performances differ from fashion?

HV: I don’t think of it as very different, it’s just another way of imagining. Of course there are functional differences: distance, lighting, movement. Dance costumes have to work for the body in motion, and sets exist in relation to space and light. But I approach it the same way, by using my eyes, my ears, and my curiosity.

h: If you had to wear one outfit forever, a personal uniform, what would it be?

HV: A jumpsuit. Probably in navy.

h: Copenhagen Fashion Week has grown a lot in recent years. Beyond the surface, how has the creative energy and cultural conversation around fashion in Denmark truly shifted since your early days?

HV: It’s changed a lot, especially in audience and scale. I was doing shows before Copenhagen Fashion Week even existed. For years I’d show both in Paris and Copenhagen. But lately we get more press and attention here than we did in Paris, which says a lot.

Scandinavian fashion used to be quite safe, lots of black and grey. Now there’s more color, more experimentation, more confidence. It’s also become more international, you walk around and hear people speaking English everywhere.

h: Do you think there’s kind of more room there for, like, emerging talent than there would be in Paris?

HV: There’s definitely room to experiment here, but if you’re doing something truly avant-garde, you still need to reach out internationally. There might be one or two stores in Denmark that get it, but to survive, you need that global audience. It’s good to be on different platforms, Copenhagen and Paris.

h: Receiving the Danish Art Foundation’s Lifelong Honorary Award is a remarkable milestone. How did it resonate with you, and has it shifted your sense of responsibility toward the creative community or your audience?

HV: It’s an honor, of course, but it hasn’t really changed how I work. Maybe it will later on, but for now, it’s more of a quiet recognition than a turning point.

h: If you were to host a dinner and could invite anyone—living or from the past—who would make your dream guest list?

HV: I’ve actually thought about that. Maybe it wouldn’t be a dinner, it could be a kind of speed dating experiment. Imagine Thom Yorke sitting across from a world leader, a student next to someone from a war zone, a celebrity beside someone living in hunger. Power and vulnerability in the same room, forced to listen to each other. It could be a speed dating set up.

If someone only talked about themselves, they’d miss the whole point, communication and exchange. That’s the energy I’d want at the table.

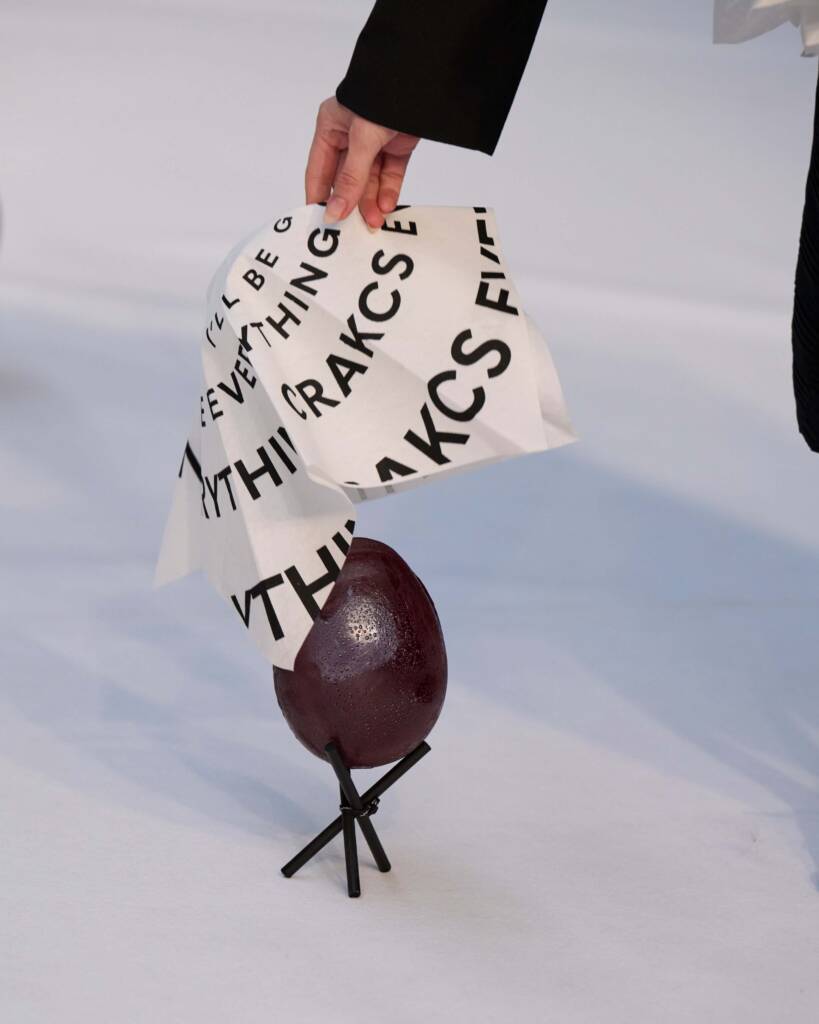

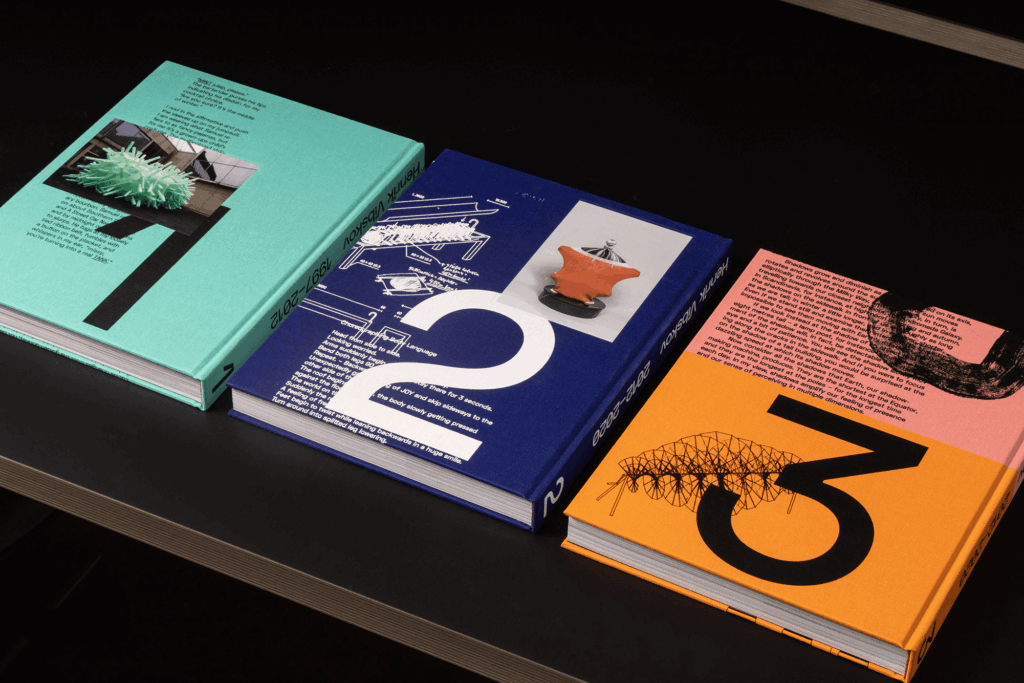

The Sun Will Shine on the Assembly Line, still

Courtesy of HENRIK VIBSKOV

Photography by FILIP GIELDA

Photography by BRIAN KURE

Words: JULIA SILVERBERG