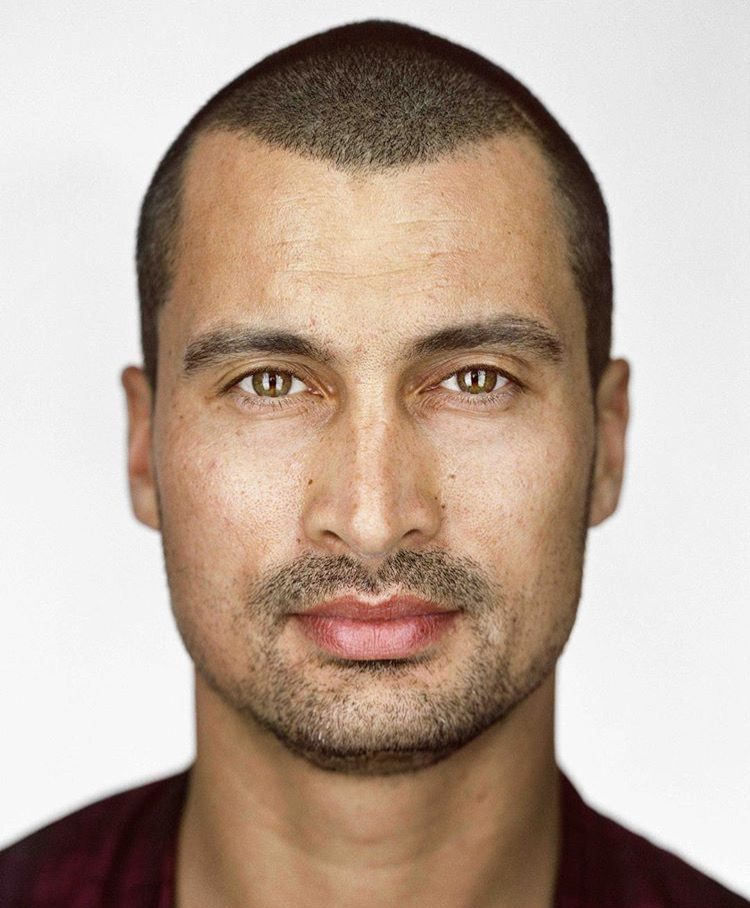

Sky Gellatly is a cultural strategist and co-founder of the creative agency and talent representation firm ICNCLST, celebrated for its ability to fuse contemporary art with the language of global brands through exhibitions, collaborations and strategic consultancy worldwide. As chief executive of the New York-based firm, he has led defining partnerships that position artists and art institutions such as Futura, MoMA, Nina Chanel Abney, and Lauren Halsey within the orbit of brands including Nike, Marc Jacobs, Comme des Garçons, and Google, expanding the reach of creative expression into the commercial sphere. Before establishing ICNCLST, Gellatly served at Complex Magazine, MTV, and Details where he honed his instinct for creating relevant, resonant content and understanding how to communicate it within the public realm. In 2023, ICNCLST launched Control Gallery in Los Angeles—an exhibition platform created in partnership with Beyond The Streets dedicated to supporting artists and creatives under the guiding belief, ‘Control to the Artist. Never over the artist’. In 2024, Gellatly also became an Adjuct Professor for Columbia University, teaching within their Graduate School of Architecture (GSAPP).

Today, Gellatly sits down with hube’s Editor-in-Chief, Sasha Kovaleva, to discuss his experience navigating the ever-changing media landscape and his deliberate interplay between creativity, business, and cultural strategy—offering a compelling model for how independent artists and companies can inform and elevate one another.

Sasha Kovaleva: Could you walk us through your professional journey—what led you to co-found ICNCLST, and who or what shaped your creative vision along the way?

Sky Gellatly: I started my career at Complex Magazine. Back then, Complex wasn’t the large-scale media and shopping conglomerate it is today. It was a print magazine focused on music, fashion, and culture. That meant many different things, but primarily it revolved around various permutations of hip-hop culture, largely in New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles, with occasional touchpoints in London, Japan, and elsewhere. This was 2003, very early in what I’d consider the rise of popular media editorialising creative subculture — Complex was really one of the first in the United States to do that at scale.

I began in editorial at Complex, where I learned how to write professionally and how to interview people of note, skills that became foundational as my career progressed.

Some of my earliest experience with online editorial also came during that period. In 2003, magazines didn’t really have websites—major news publications did, but Complex was one of the first independent publishers to seriously move into the online space. From Complex, I went on to MTV Networks. Twenty years ago, MTV was still the leading youth culture television network and, at the time, was becoming a major global online platform for youth culture as well. In addition to continuing to write, I learned how to produce video. MTV was a massive network then, with both news programming around music and culture and regular music video rotation. Working alongside veteran journalists who had built their careers in video rather than print, I learned how to produce news segments.

MTV was truly the epicentre of youth culture in North America at that time. Almost every day, a major band or artist would pass through—often one or two every few days—along with actors and entertainers from Hollywood. I gained extensive experience interviewing and engaging with public figures, which proved invaluable later on. Interviewing the likes of Mariah Carey and Pharrell Williams at the age of 25 built confidence and context. Fairly early in my journey, I stopped feeling nervous around people of note. After interviewing so many of them, you realise they’re just people—and that you can speak to them as such, and be human.

While at MTV, Viacom was investing heavily in online editorial, so alongside my editorial work I also did copywriting, much like I had at Complex, but now for mtv.com. From there, I fast-tracked into a more entrepreneurial phase. I left MTV and began freelancing for publications like GQ, Hypebeast, and others, while also starting to represent talent independently.

The first artist I represented was DJ Neil Armstrong, who went on to tour with Jay-Z for many years. Through that experience, I learned a great deal about talent management and about being close to a machine like Jay-Z’s touring operation. I then began representing the photographer 13th Witness, who is Futura’s son. I was able to apply my background in video and film production from MTV to help him scale his work. At the same time, while Neil was touring with Jay-Z, Tim was touring with John Mayer as a photographer. It was an intense and fascinating period, freelance writing while managing my first two clients, both on global tours. It was very much full-time.

Around then, two significant things happened. A friend of mine started a marketing agency called Team Epiphany, which I later became a partner in. Separately, my best friend from high school, Kenji, and his best friend from college, Damany, launched a business called Flight Club. During this transitional phase, I was managing talent independently, beginning to work with my friend’s agency, and learning how to write decks and presentations. Through Flight Club, I moved more formally into marketing communications, no longer as a journalist, but as someone representing brands and retail partners, working with artists and product collaborations.

From roughly 2010 to 2015, my focus was largely on Team Epiphany, where I became one of three partners. I continued managing Neil and Tim, and around 2012 I took on Futura as a client—my first visual artist. On the agency side, I spent five years running social media for Nike. That role brought together everything I’d learned up to that point — copywriting, video production, editorial strategy—into a consulting position helping Nike shape its social media voice. As an agency partner, I helped launch Nike’s Instagram and Twitter accounts and, at one point, with my team, managed 11 different sport communities for Nike. It was intense. I often say I earned my MBA while consulting for Nike; I owe my friends at Nike for so much of who I am today.

Nike remains my most significant and longest-standing brand client. At the same time, I was managing Futura, 13th Witness, and Neil. Around 2015, I had a realisation. Having spent years immersed in media, branding, and communications, I watched influencer marketing rise, particularly between 2012 and 2015, as it became the dominant model in brand marketing. My intuition told me that as influencer marketing became ubiquitous, it might actually be more compelling to work with artists instead of influencers—people with singular perspectives, creating work, concepts, and movements that only they could make.

Given my background, I saw an opportunity to build meaningful bridges between brands and artists, something very few people were doing at the time. Having grown up in a creative, entrepreneurial household, surrounded by art, sport, and culture, this felt intrinsic to who I was, not just what I did. At 35, I decided it was time to take a leap and build something aligned with my passions, not just sheer commercial logic and immediate scale.

That decision led to ICNCLST, a synthesis of my experience in brand building, editorial storytelling, and talent management. I wanted to create an agency rooted in what I genuinely loved. The path hasn’t been linear, but today half of our work focuses on helping brands develop communication strategies that often evolve into artist collaborations, content creation, or live experiences—all expressions of brand storytelling and world building. The other half centres on talent representation, helping independent creatives author their careers and collaborate with brands in a world where social media enables direct connection with audiences like never before.

Ultimately, my vision has been shaped equally by my upbringing and experience, growing up in an artistically minded household, having entrepreneurial parents, and living in New York, a city where you’re free to choose your own adventure. All of that brought me to where I am today.

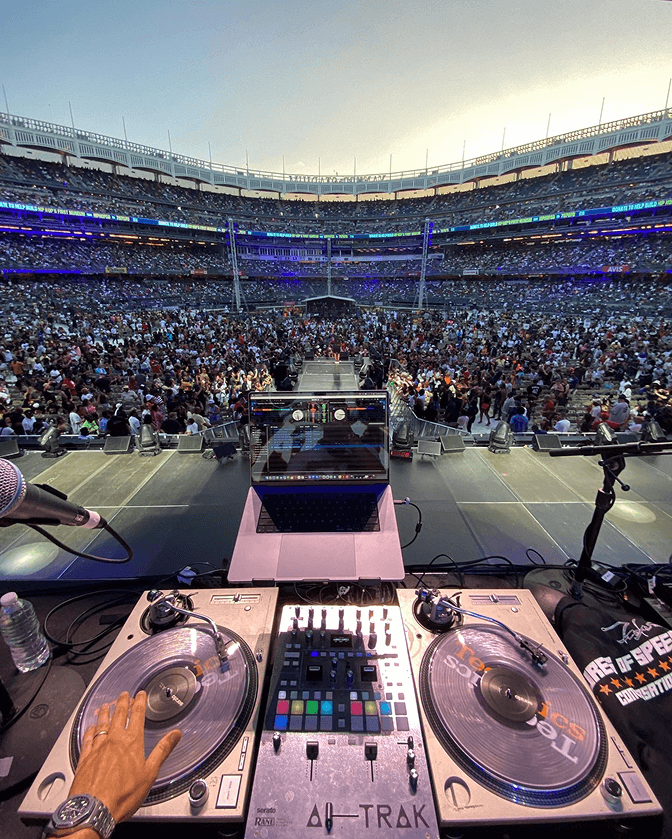

Courtesy of SKY GELLATLY

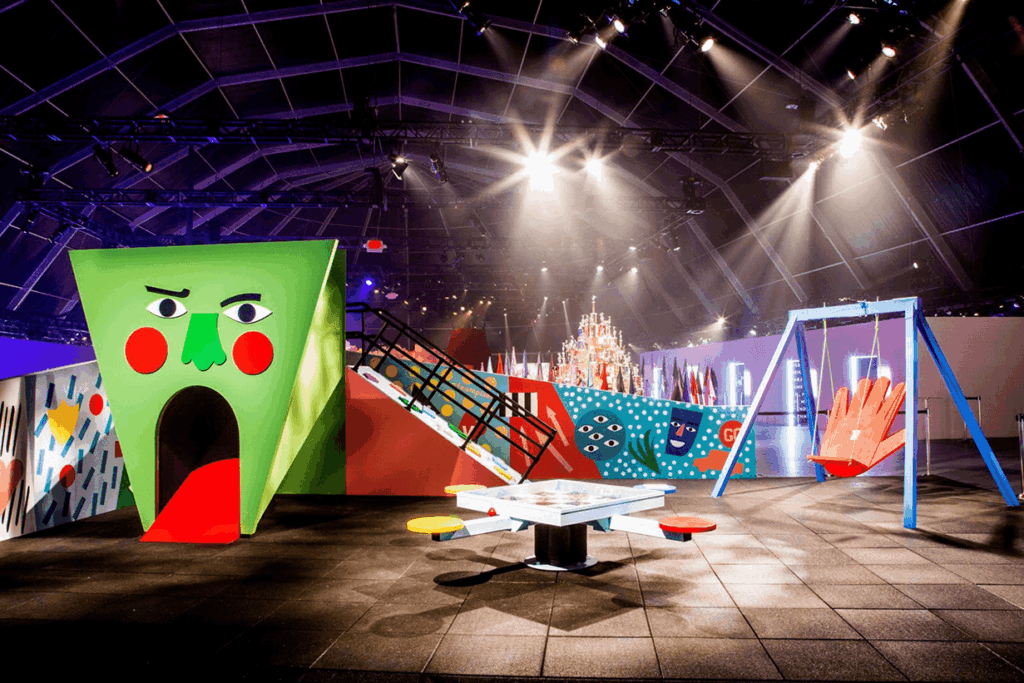

Courtesy of SKY GELLATLY

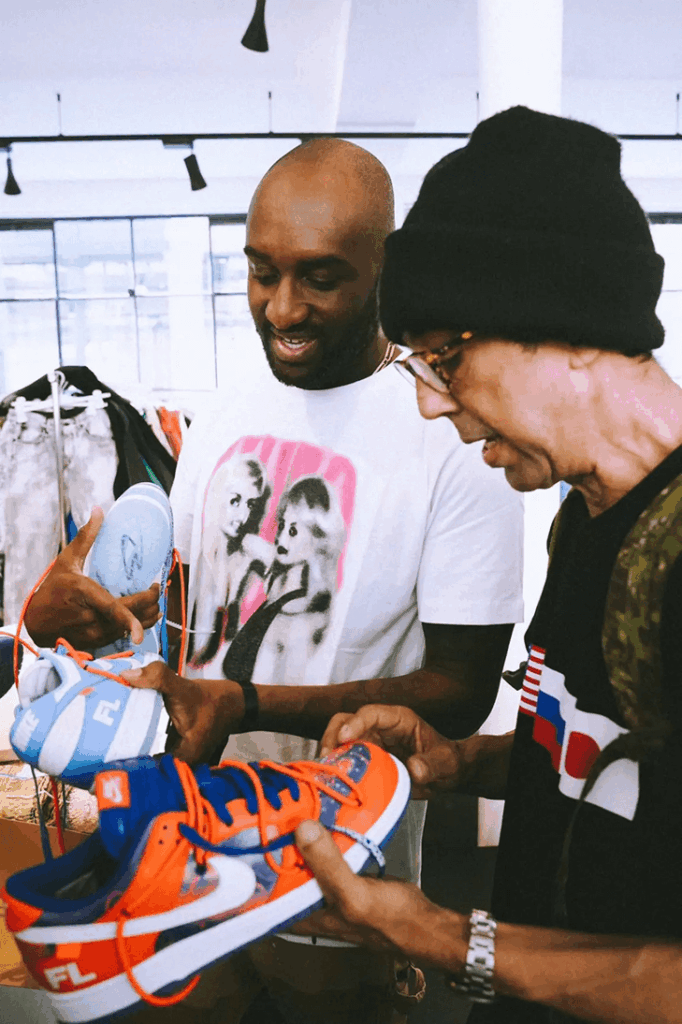

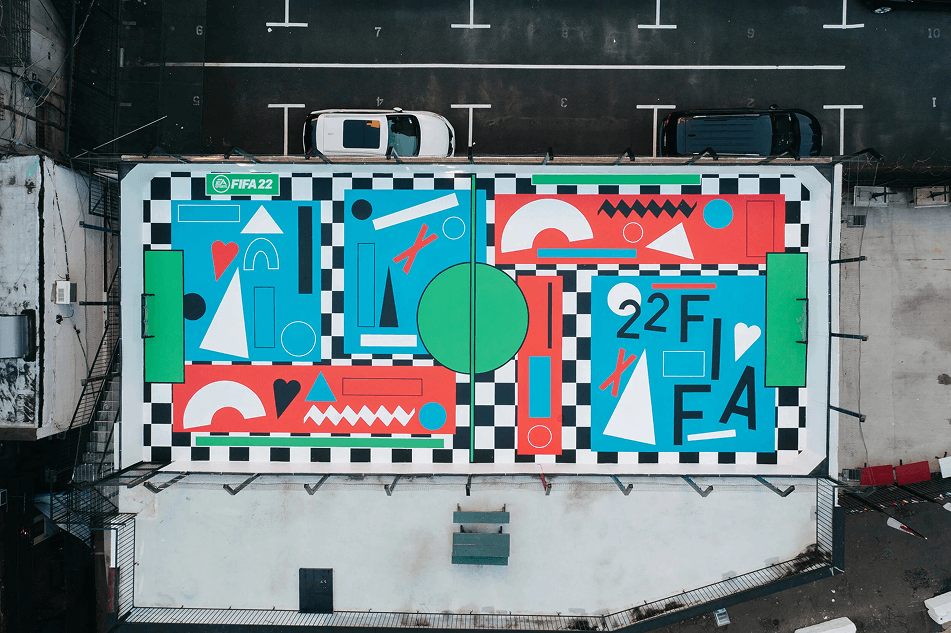

Courtesy of OFF-WHITE and NIKE

SK: ICNCLST is known for bridging brands and talent. When pairing a brand with an artist, what’s more important: alignment of aesthetics, shared values, or potential cultural impact?

SG: When we represent artists, success can mean many different things, which is why it’s so important to define what success actually looks like. It varies from engagement to engagement and from client to client, every situation is different. For me, success is a combination of several factors. First and foremost: are the artist’s personal values, interests, and beliefs being amplified through the collaboration in some meaningful way? That should often be the primary criterion. The second question is: who is this for? Does the collaboration allow the artist to speak to their existing audience in a new way, or does it enable them to reach an entirely new audience?

Success also means thinking from the outset about what kind of dialogue the project will create once it’s completed. What new conversations become possible because this collaboration exists? Aesthetic considerations matter as well—the artist’s ability to meaningfully influence a brand’s commercial products, lending symbolic value while maintaining authorship, creative freedom, and the right to do something genuinely new. That aspect is paramount.

We operate in a landscape where licensing and collaboration are often grouped together, but they are fundamentally different. A collaboration involves living artists with intentions, just as brands are run by people with their own values and beliefs. Licensing, on the other hand, is usually about taking existing IP owned by an entertainment company, turning it into a surface or fabric, and allowing a brand to apply it across products for retail. Those are two very different models. One is perhaps more serialized or “superflat” than the other—which is more alive, honest, vibrant, and of-the-now.

In true collaboration—between living artists and living creators—it’s essential to establish why the collaboration is happening and who it is meant to serve. When those questions are clearly answered, success can be intentionally designed from the beginning, and not purely in commercial terms. It becomes about alignment: Why is this brand interested in this artist? Why is this artist genuinely compelled to work with this brand? Are the economics fair and equitable? Are the artist’s rights protected throughout the process?

That shared understanding is ultimately what defines success can, should, or could be.

SK: Can you share a project where the collaboration between brand and talent exceeded your expectations, and why it worked so well?

SG: We’ve been very fortunate to be part of some truly amazing collaborations. Shepherding the Nike and MoMA collaboration in 2024 was undeniably pretty unreal. But one in particular was especially memorable, as it really demonstrated the power of collaboration when two creative forces genuinely come together—perhaps as a result of kismet, goodwill, and integrity.

Before the pandemic, Futura and I had a very rare sequence of opportunities. We had worked on incredible projects with Louis Vuitton through my longtime friend Virgil Abloh. Coming off those projects, Futura was creating site-specific work and, during Virgil’s second Louis Vuitton show, he performed a live intervention, painting in real time during the runway presentation. That took place in January 2019.

Then, in the summer of 2019, Futura was commissioned by Virgil to create key core artwork for an entire Off-White collection, which was paired with two Nike sneakers that debuted on the runway without leaking beforehand. As part of that Off-White presentation, we also created a sculpture designed in a custom colourway that correlated to the Nike sneakers—inspired by the optimism of Michael Jordan while at UNC. It was a truly magical moment, just an incredible experience.

Not long after the Off-White show, Futura and I were in Japan. Through our previous work with Dover Street Market in Singapore, I worked to get us connected to the Comme des Garçons team. One thing led to another, and soon we were meeting with Adrian Joffe and Rei Kawakubo to discuss a potential collaboration with Comme des Garçons, one that would show in Paris in January 2020 and be commercialised later that year.

What made that moment particularly significant was the timing. It was coming directly after the Louis Vuitton and Off-White collaborations. I remember speaking with Virgil out of respect, saying, “This opportunity has come up, what do you think? It’s so close to the LV and Off-White projects.” And Virgil said, “If Rei asks you, you have to do it. She might never ask again.” I’ll always remember the generosity in that response and his understanding of the magnitude of working with Rei. He understood the cultural magnitude that she represented for Futura—a cultural hero to both of us as teenagers.

We went on to create a collection with Comme des Garçons, and the craftsmanship of their design team is something truly exceptional—tactile, exacting, and deeply creative. For the Comme des Garçons SHIRT line, the pattern-making process resulted in incredibly beautiful, multi-layered shirt constructions. Unlike many collaborations that rely on digital line art, these patterns were hand-drawn by the Comme des Garçons team. The execution felt deeply artisanal, artistic, perhaps even ascetic.

Fast forward to the runway show. It was an extraordinary moment. In the eyes of artists, Comme des Garçons is perhaps the most artistic fashion house—unmatched in credibility and authenticity in how it engages with creative work. After the show in Paris in January 2020, everyone was excited to commercialise the collection. Then, of course, the pandemic happened.

What made the project especially meaningful—beyond the context of following LV and Off-White, and Virgil’s complete grace and support—was what happened next. When it came time to commercialise the collection during the pandemic, we had originally conceived a series of large-scale sculptural spheres to be installed in Comme des Garçons stores worldwide, as well as at Dover Street Market locations. Despite the world being effectively shut down, Comme des Garçons stayed true to the artistic intent and went ahead with building and installing these sculptural structures at retail.

That commitment meant a great deal, not only in terms of the design process, but in seeing the project through despite everything changing between conception, debut, and commercialisation. Even though we couldn’t host events or large-scale content activations, from an artistic perspective, it was handled beautifully. That level of dedication made the entire experience truly special. CDG is, simply put, as amazing and integrity-filled as any creative could imagine.

SK: In your opinion, what does it take for a collaboration today to stand out in a saturated fashion and lifestyle market?

SG: For a collaboration to truly stand out, there are a few key elements. Very often—whether we’re talking about fashion or even industrial design and furniture—it comes down to whether an artist is genuinely working with the lead creative at a brand or fashion house. When two artists are in real dialogue, that’s often when the most compelling work happens.

By contrast, when it’s simply, “We need your graphics for something, that will go on a sneaker or product,” the result can feel flat. In those cases, it isn’t really a collaboration; it’s not a synthesis of creative energy between two figures coming together to make something unique.

What really cuts through is enthusiasm. You can almost immediately sense when a brand or an artist is genuinely excited about a collaboration. Often that’s because, for the artist, the project allows them to express something personal, something biographical—who they are as a person beyond their public persona or artist name. Those are the projects artists tend to promote most passionately, well beyond what’s contractually required, simply because they’re truly excited that the collaboration exists. In that sense, you might say the collaboration is authentic.

A good example is Futura. He’s a lifelong baseball fan, he played when he was younger, and he listens to baseball on AM radio while he paints. If you know Leonard, he’s a salt-of-the-earth New Yorker and a huge baseball fan, though most people wouldn’t necessarily know that. Of course, he could make an abstract painting using the colours of his favourite team, the New York Mets. But doing something deeply rooted in baseball is somewhat incongruous with his usual studio practice as an artist exhibiting in galleries and museums.

So when we were able to bring him a collaboration with the New York Mets, it became incredibly meaningful. He threw out the first pitch at a game. He designed a baseball cap, a jersey, and a bobblehead for the occasion. His son caught the first pitch he threw. That collaboration mattered so much because he promoted it heavily—not out of obligation, but because he was genuinely excited to share how much the Mets meant to him, how important baseball was in his life, and how it connected to memories of playing catch with his son on the streets near their home.

When collaborations like that happen—ones that may feel unexpected or anomalous, but that clearly answer the question of why—the impact is very real. In this case, the Mets organisation was equally excited. When they met with Futura and me, they said, “This isn’t just Futura the artist—this is one of our biggest fans. He’s the perfect person to work with.”

That level of authenticity and excitement is tangible. You can feel it on a human level. Beyond the quality of the creative execution, you can tell how invested partners are by how they support, advocate for, and promote a project. Excitement begets excitement and that’s what truly cuts through.

SK: What trends or shifts in fashion marketing do you think are overhyped, and which are genuinely reshaping the industry?

SG: I do think that over the last fifteen years or so, collaboration has become highly standardised—even in the way collaborations are acknowledged. It’s always brand X and creative Y, an independent creative force paired with a company. Even the nomenclature—the way collaborations are titled and framed—has become stale. That part feels tired, and even the vernacular around collaboration would benefit from renewed energy and a sense of intentionality. That’s something I think about a lot: canon, vernacular, semiotics, and value.

Within the canon of marketing, advertising, and art, collaboration functions as a kind of signifier but there’s so much more at play. Cultural exchange, semiotics, and deeper layers of meaning could be brought more fully into the realm of collaboration. Even something as basic as how a project is titled—brand X with artist Y—could be approached in a more thoughtful, beautiful, and distinctive way.

I also think the concept of endless “drops” has run its course. There’s clear consumer fatigue around highly hyped products where the core idea is simply scarcity. The storytelling often revolves around creating urgency rather than meaning—and that feels increasingly hollow.

Younger generations—Gen Z and Gen Alpha—have a very different relationship with brands, authority, and trust. When we talk about what makes a good collaboration, and when I reference someone like Futura, it’s important to ask: who are these projects actually for? They’re not meant to appease forty-five-year-old marketers, artist managers like myself, or distant industry audiences. They should be speaking to youth culture.

At their best, collaborations can help democratise art—meeting young people where they are, inspiring them, and allowing them to engage with art and culture through accessible products and experiences. Price point matters. Distribution matters. Presence in everyday spaces matters.

If you talk to Gen Z or Gen Alpha kids about things like NFTs, for example, many of them didn’t reject the idea because they didn’t understand it conceptually. They rejected it because it felt shallow and transactional. Similarly, drop culture tends to appeal most to people interested in reselling as a business, rather than engaging with culture itself.

As a discipline, collaboration—as a school of marketing—would benefit from more considered storytelling. Less can truly be more: fewer collaborations, executed with greater intention and depth. Over the past few years, brands have applied a tremendous amount of science and economic logic to these projects. If some of that focus could shift back toward art, beauty, and nuance, it would resonate far more deeply with younger generations. That’s ultimately what they’re looking for.

SK: If you could give one piece of advice to young creatives looking to work at the intersection of marketing, fashion, and cultural influence, what would it be?

SG: I’ve always led with what I was interested in—but honestly, it’s been entirely accidental. None of it was planned. I’ve failed so many times. So many businesses I tried, ideas that didn’t work, ideas that half-worked. I actually have far more failures and half-successes than outright wins. What I tell my son—and what I also say to younger people—is something very similar to what Virgil used to say. You can overthink anything. But the most important thing is to have an idea, come up with a plan, put it into the world, and execute. Because if you don’t execute, you’re not really trying.

You’ll never know whether an idea is special only to you or whether it holds value for a broader audience unless you put it out there. A lot of young people today understandably live in a world where they see people becoming famous very quickly, and they start to see that as the standard rather than the anomaly—which they’re exposed to more often now because of social media. It can be intimidating. They feel like they need to be a unicorn entrepreneur, or an artist with a Yale MFA signed to one of the top four galleries in the world, or else they’re not successful — or not valuable.

What I always say is: be excited about the fact that you’re going to fail many times. In those failures, you build conviction. You experience small wins. You learn. Your career becomes a series of rapid prototypes. If you think about it through the lens of design thinking, it’s very real. I’m not the smartest person by any means. I moved to New York and didn’t know anyone. I failed fast. And sometimes you have to work three jobs so you can work the one job you actually love — do it. That’s what I had to do.

And imposter syndrome—everyone falls victim to it. But sometimes you are good enough. Sometimes your idea is special enough. The most important thing is to put it into the world. Because if it doesn’t work, that’s okay. If you’re an idea person, you’ll have another idea. So don’t worry about it.

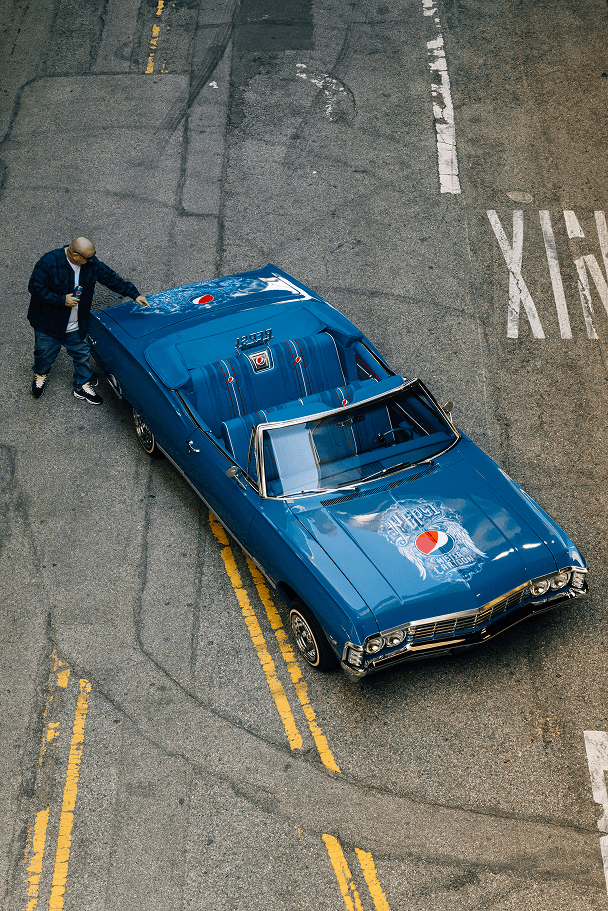

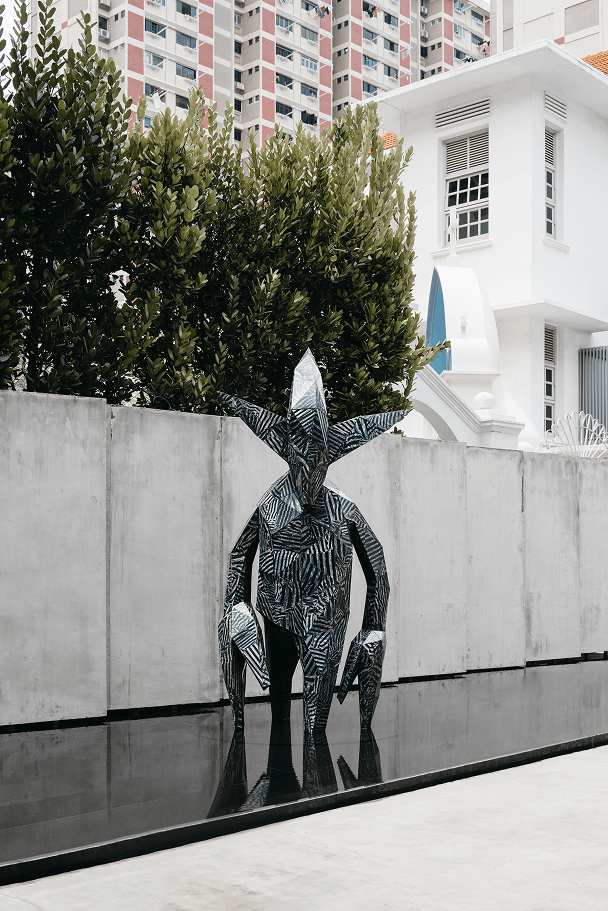

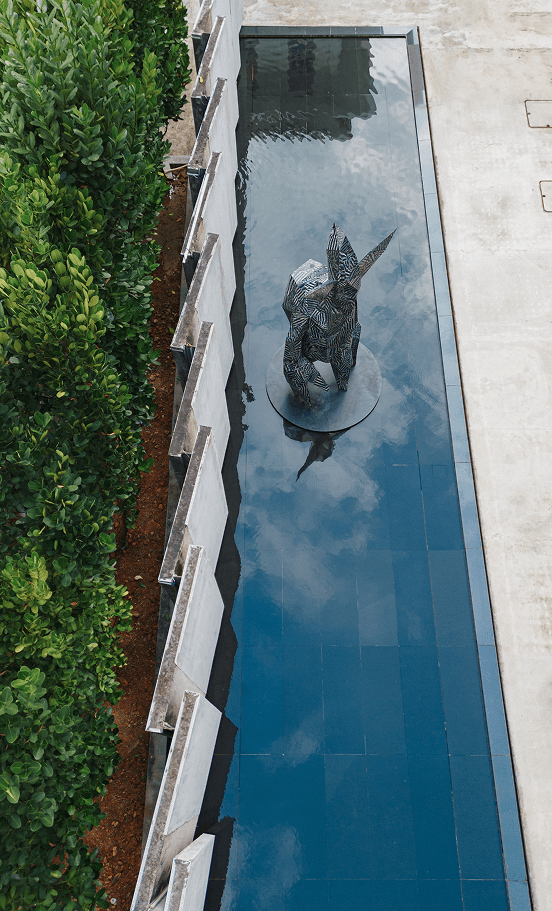

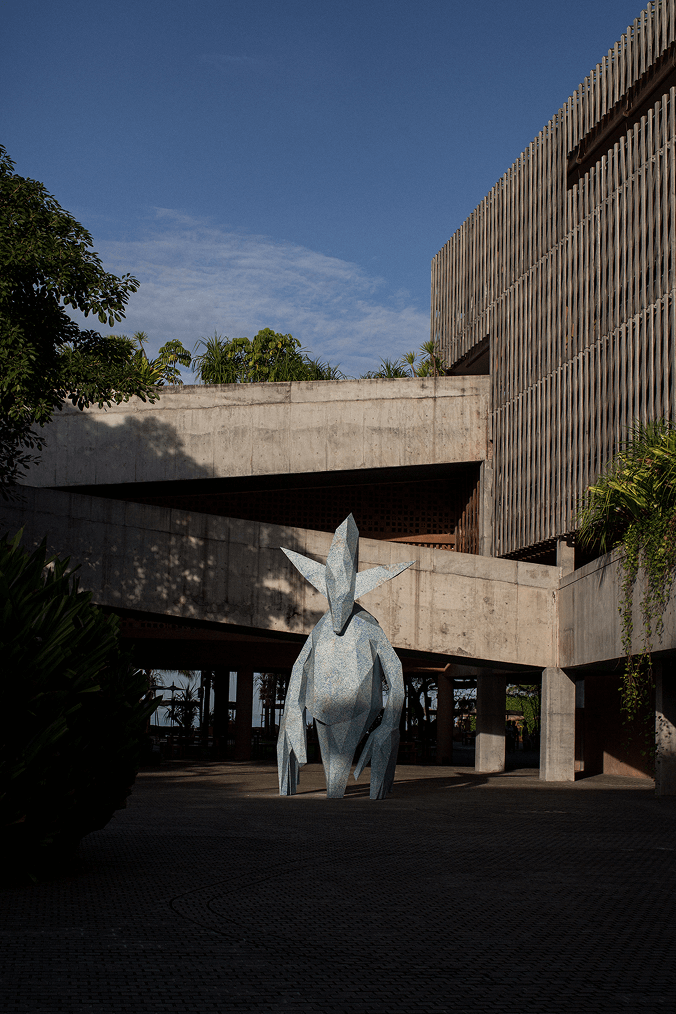

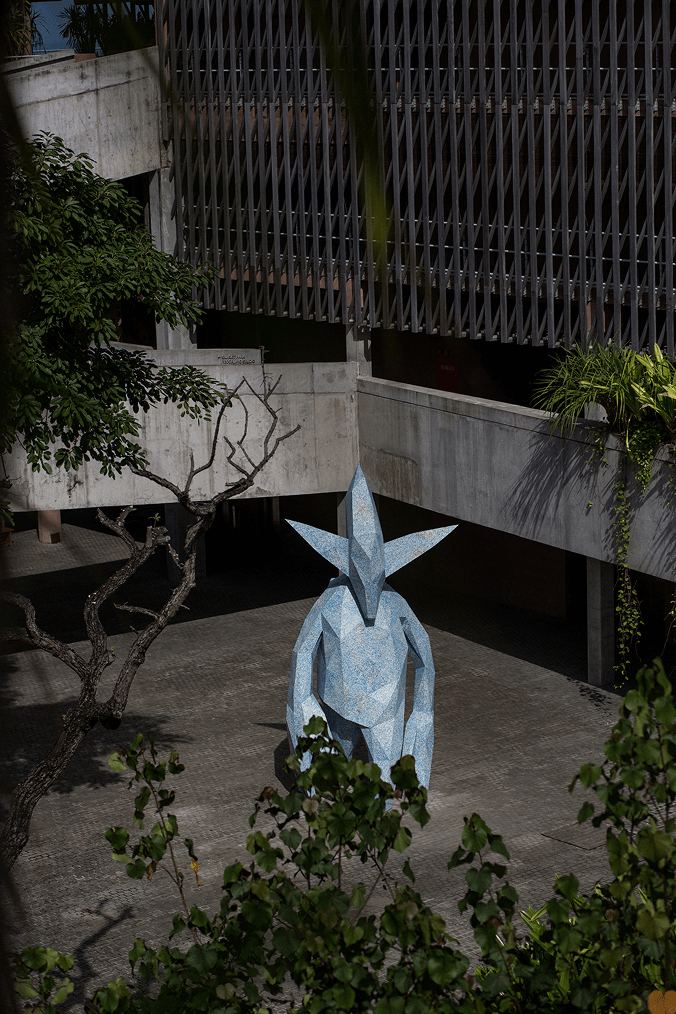

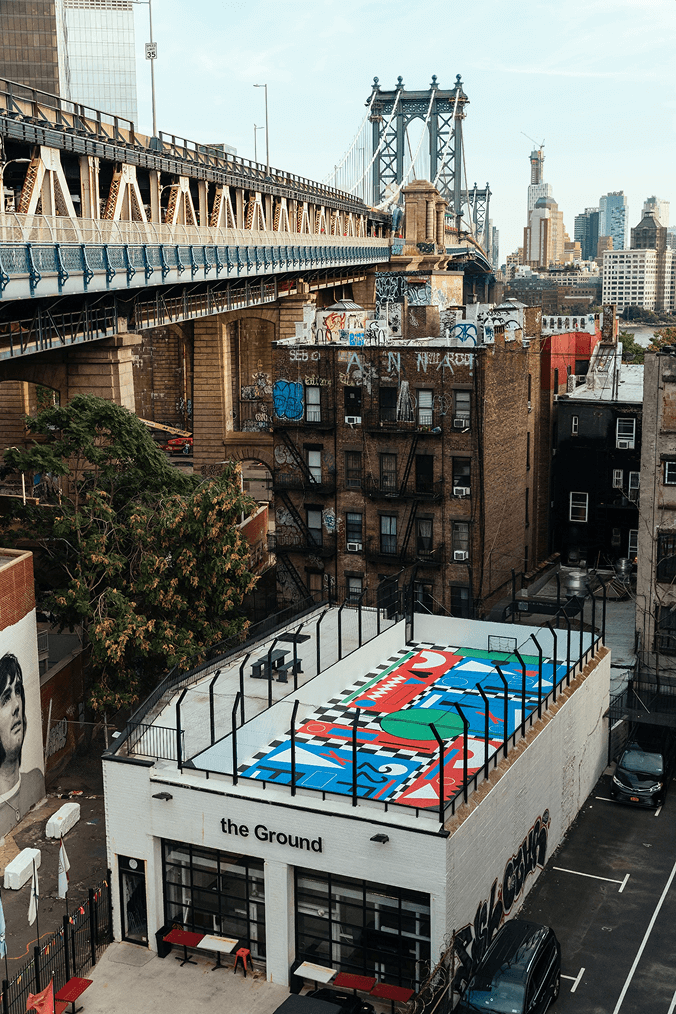

Courtesy of STUDIO PERIPHERY

Courtesy of YK, Pointman Potato Head Singapore

Photography by REGIS COLIN BERTHELIER for NOWFASHION

Photography by REGIS COLIN BERTHELIER for NOWFASHION

SK: How do you see the intersection of digital culture and physical experiences influencing brand strategies in the next 5–10 years?

SG: When you think about the younger generation—kids around fifteen, or really eighteen and under—they’ve grown up playing Minecraft, Roblox, and Fortnite. They’ve presented themselves, or versions of themselves, on TikTok, Instagram, and other platforms. Many of them are already interested in, or at least familiar with, coding and related technologies. For them, the idea of a digital ecosystem is completely comfortable territory.

They’re already blending the digital and the physical in their everyday lives—constantly, intuitively. They’re also the generation grappling with moral questions around AI: what it means, what its future might be, and whether it will replace or amplify their careers in the years ahead. These are things this generation is actively thinking about.

Because of that, I don’t see a future where immersive digital experiences like TeamLab, for example, simply disappear. They may evolve. They may become hybrids, combining digital media with tactile, physical engagement. But they’re not going away. The digital economy is very much here to stay.

You can see this clearly in gaming. Digital goods, fashion products entering games, soccer cleats being sold inside virtual worlds—this is an economy that adults have somewhat danced around through crypto. For kids, though, it’s much more literal. There’s clear utility: they buy digital goods, apply them, and use them within games.

If you imagine today’s teenagers in their twenties, having grown up with this as a standard practice, it will be fascinating to see how they continue to evolve digital and physical brand experiences, as well as art experiences. This is not my generation—it’s theirs. They’re the first to grow up in a world that has always been digital.

They’re the ones who truly understand what this is all about. Adults may have helped get things off the ground, but the real innovation will come from this next generation. Even their sense of place in the world has always been inextricably tied to digital life. That’s fundamentally different from the perspective of someone like me, who grew up in an analogue world—without mobile phones, without email.

Ultimately, the future will be shaped by those who have lived entirely within a digital environment their whole lives.

SK: If you could invite any five people—living or dead—to a dinner where you’re certain they would all come, who would you choose?

SG: I would invite my great-grandparents—as many of them as I could—from both sides of my family. On my mother’s side, they came from Ireland to the United States with no means. I wish I knew more about that journey—not just where they came from, but what it was really like, and how it ultimately led to me being where I am today.

On my father’s side, there’s family history in the Philippines and Greece—again, people who travelled long distances and made enormous decisions to leave behind their homes and families in pursuit of opportunity, or simply a better life.

As much as I could name any number of famous people to sound thoughtful or impressive, I’m at a point in my life where I genuinely wish I knew more about the generations before me. I want to understand the family members who made those choices—choices that made my own life possible. I’d want to thank them. But I’d also want to hear their stories—their journeys. I imagine they were frightening, exhilarating, and filled with hope in their own way.

h: Who has been the most inspiring to you in your career?

SG: When I was a teenager, I was most inspired by the illustrations and art direction of Shawn Stüssy. Early Stüssy ads and taglines painted a picture of the world for me that could be equal parts righteous and also declarative. So was the case of C. R. Stecyk III as his work with Powell Peralta, in addition to the “worldbuilding” skills of Public Enemy and Nine Inch Nails. I also really enjoyed Georgia O’Keefe’s depictions of New Mexico as a kid—realist, but of course also very emotional—as well as what Noguchi Akari lamps made my childhood home feel like, in terms of environmental adaptation, when either on—or off.

As an adult, I feel like I have different pockets of inspiration. Within “communication arts”, I am inspired by—perhaps in a similar way that I was drawn to Shawn Stüssy—by Barbara Kruger, Jenny Holzer, Lawrence Weiner, and Stephen ESPO Powers. Within the fields of marketing and advertising it’s George Lois, followed by John C. Jay from Uniqlo, and both Greg Hoffman and Trevor Edwards from storied Nike tenures. Then there’s perhaps the school of “collaboration experts” and those folks are undeniably Fraser Cooke, Drieke Leenknegt, and Paul Mittleman. In terms of curatorial—meets—operator—superheroes it would be Jeffrey Deitch, Anne Pasternak, Karen Wong, and Paola Antonelli. In terms of overall spectacular worldbuilding it is Nam June Paik, Theaster Gates, Yayoi Kusama, Takashi Murakami, and Cai Guo-Qiang. As for “language” it’s Lupe Fiasco, Jerry Saltz, Arthur Jafa, Tilda Swinton, Patti Smith, and David Bowie.

I think that the most valuable part of my career is that I get to work with artists and brands who actually inspire me—as does my team itself. Kicking off my 13th year working with Futura 2000 is as thrilling as “what’s next” in year one of working with a generational force like Lauren Halsey. The trust and belief that iconic clients such as Nina Chanel Abney and Nike put in my team is pretty watershed moment to be completely honest. Seeing my team do spectacular work—and me allowing them to drive and grow—is very rewarding. I am inspired as much by what clients and collaborators like Tremaine Emory and Angelo Baque stand up for on behalf of their communities, as I am by my team and I getting to contribute to not-for-profit ventures like Free Arts NYC, Street Soccer USA, or the Virgil Abloh Foundation.

Keeping Virgil’s name, energy, way of being, and “wave” in the zeitgeist is of paramount importance to me. And above all, my wife, son, and family are my biggest inspiration and driving force—every minute, always.

SK: How would you describe the future in 3 words?

SG: Ask my son.

Digital editor: ISABELLA MICELI