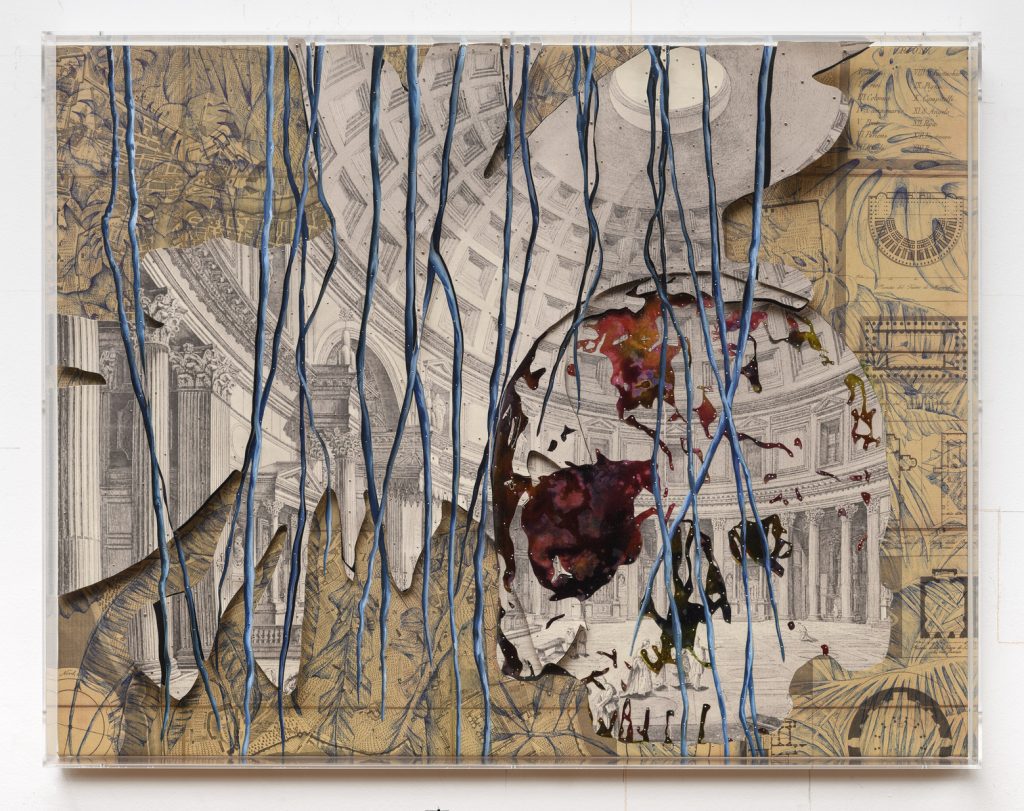

Antropocene 73 (PANTHEON), 2023

Photography By GIORGIO BENNI

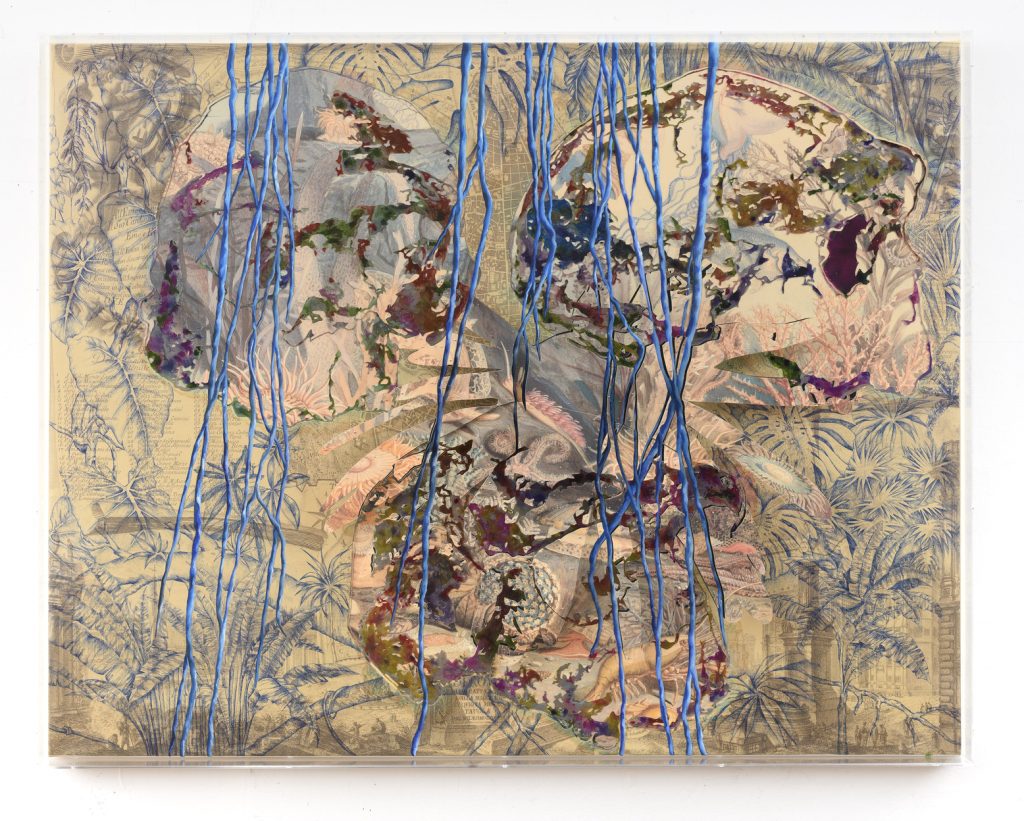

Antropocene 55, 2023

Photography By GIORGIO BENNI

Pietro Ruffo, a Rome-based artist, shares his unique perspective on contemporary art and its connection to the beauty of human-touched landscapes of history. Ruffo’s experiences stretch all across the continents — from studying at Columbia University in the US to collaborating with Valentino in Rome and Miami, and Dior in Paris and Venice. As he delves into the concepts of research and paper craftsmanship, Pietro teaches us about the importance of asking questions.

hube: Your work often intertwines with philosophical, social, and ethical considerations. Could you elaborate on how these considerations influence your choice of mediums, such as drawing and carving, as instruments for analysing historical and contemporary dynamics? How do these mediums contribute to the conceptual dimensions of your art?

Pietro Ruffo: My work is mostly based on research. It’s something I have been doing for a very long time in different stages of my life.

In 2010, I had an opportunity to join Columbia University with a research fellowship with the Italian Academy for Advanced Studies. I wanted to study American liberal thinkers like John Rolls and Robert Nozick to understand their perception of the world. I would always watch my friends studying other subjects: math, biology, economics… I would see them with all of their books open on the tables and notes on paper. What were they highlighting with yellow?

Imagine you are a student taking notes during a lecture or while reading a book. For me, it’s the same, I also take notes. But my notes are graphic. So the things I display in my work are not statements but more like a representation of my desk with all of the research on it: images, photocopies, drawings, etc. When I present a show, it’s like presenting my notes for everyone to see — they can come up with their own ideas of what my work conveys.

My mediums are paper, pen drawings, watercolours, and cutouts.

h: Your collaborations with such fashion houses as Valentino and Dior involve designing urban-scale installations for high-profile events. How does the transition from creating large-scale art installations for galleries and museums to fashion events impact your creative process, and what challenges or opportunities does this interdisciplinary approach present?

PR: Let’s start with art history. If you think of such eras as the Renaissance or the Baroque, all across Europe artists would mainly work through commissions. Who were the people that could ask an artist for a commission? Big rich families for their gardens, the Pope in Italy for the Vatican City or other churches, and the municipality of a city. In the modern day, it’s becoming more and more difficult to create something for the city, — and I am mainly talking about my country, Italy, here — to be asked for a commission. It is not possible to build anything new in Rome because it’s a historical city — the municipality would not ask an artist to create a new fountain, for example. And you can rarely meet big family patrons nowadays, so commissioning for them is also not always an option.

I think fashion houses are the patrons of today. In the modern world, the relationship between art and fashion is direct and undeniable, and fashion houses can choose to work with artists. It’s a win-win situation for everybody — fashion houses do not impose any limitations on the dream an artist has. Those types of collaborations have given me a huge opportunity to expand my way of thinking.