Jack Kabangu, a Denmark-based Congolese artist, introduces his latest exhibition titled being in love with my work is a gift, but at the same time also a curse to be held at Jupiter Contemporary in Miami. We sat with Kabangu just a few days before the opening to discuss the joys and the hardships of being an artist, the source of his inspiration, and the freedom of creativity. Enjoy!

hube: Could you provide insights into the inspiration behind your upcoming exhibition, being in love with my work is a gift, but at the same time also a curse, featuring at Jupiter Contemporary in Miami?

Jack Kabangu: The idea behind the exhibition is that you experience both the ups and downs of being an artist. When you work with your biggest passion, it’s the coolest thing in the world. But it can also be so hard to just stop and “take time off”. Distinguishing between work and free time is challenging, and it’s even harder to take a break without thinking about art.

h: Among the works featured in the show, could you tell us a bit more about one or two pieces that hold particular significance to you and reflect on the stories or emotions behind them?

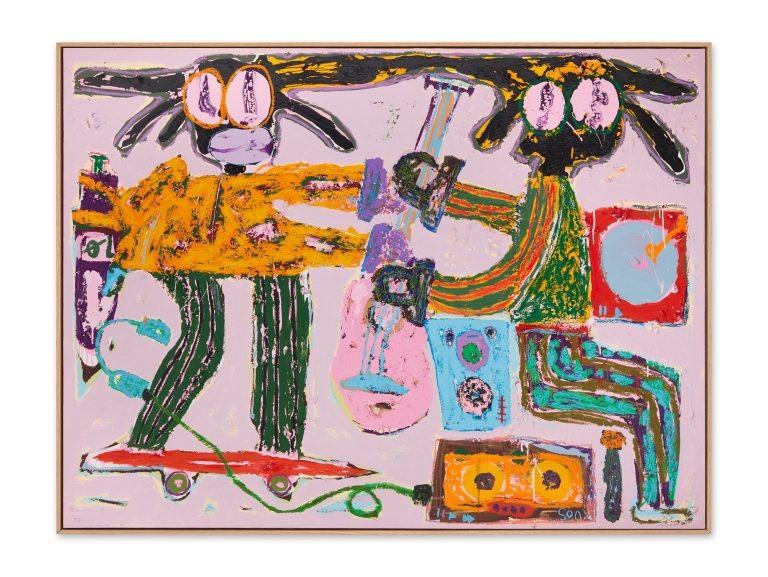

JK: The piece flyvende bolde (flying balls) is about managing multiple tasks simultaneously, symbolising the fun of handling a lot at once but also the challenge of keeping track of various projects, ideas, and ongoing commitments. I find joy in having everything up in the air simultaneously, but there comes a point where I cannot stay focused anymore, so I drop all the balls. The fun ends.

I am not mindful of my limits sometimes, so often I end up picking up the extra ball – an extra task. This, in turn, makes it impossible to keep them all “in the air” and juggle them without making a mistake.

h: The terrified faces in some of your works reflect family experiences of war. How do you balance conveying intense emotions while maintaining a visual balance in your compositions?

JK: When I create a piece, there are no set rules, guidelines, or preconceived thoughts – the works evolve based on the feelings of the moment. I never have a predetermined idea of how a piece should conclude or a visual plan for its appearance or intended reflection. I only grasp the meaning of the work once it’s completed, and even then, I try to keep its history and significance open by avoiding forming a personal opinion. This allows me the flexibility to add more details or alter the narrative through subtle additions.