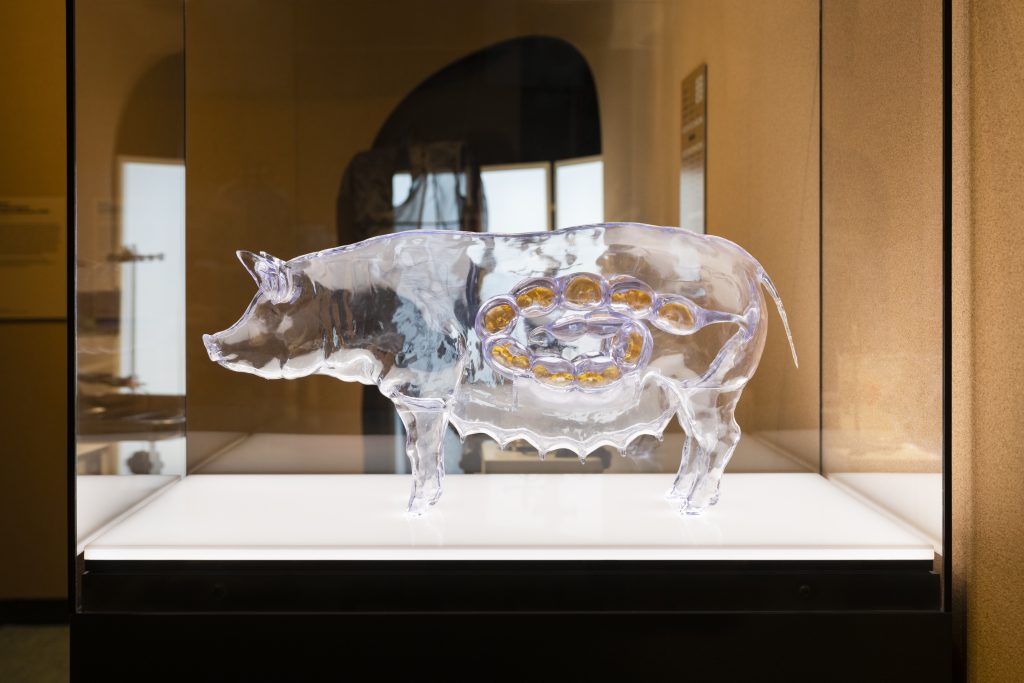

The Surrogacy, 2022

Photography courtesy of ANI LIU

Small inconveniences, 2019

Photography by HANNEKE WETZER

Ani Liu describes herself as an artist who is always looking; as an artist who thinks with her hands. Her practice investigates the intersections between art, technology, and science through research-based experimentation and reflections on the environment, society, and culture. Currently an Associate Professor of Practice at the University of Pennsylvania, the New York-based artist’s most recent works tackle topics of labour, motherhood, and the biopolitics of reproduction.

hube: Science and art are two entities that originate from human consciousness. They form the rational and emotional boundaries of human cognition. It could be said that your work tries to cross these boundaries simultaneously. Would you describe yourself as an artist or a thinker?

Ani Liu: As a transdisciplinary artist, I identify deeply with both making and thinking. Traditional disciplinary boundaries don’t apply very well anymore; depending on the project, I might be using traditional tools of sculpting, woodworking, moulding, and casting, but also digital tools, such as laser cutting, 3d printing and using a CNC. Depending on the specific work, I might be working within electronic engineering, chemistry, or computer programming. I feel lucky to have an artistic practice in which I can explore different areas of research and deepen my understanding of the world through different lenses. I don’t believe in separating people into emotional or rational thinkers. I think we can see now that cognition is incredibly integrated, and we need to be emotionally intelligent in addition to reason to navigate living.

h: Debates around gender identity remain prominent for both artists and society. Presumably, such fierce disputes are provoked by our emotional nature. Science, on the other hand, lacks emotions. Do you think science might become that tool that helps these opposing sides reconcile?

AL: While I deeply believe in evidence-based knowledge, science is conducted by humans, and as humans, we have our shortcomings. Just as we can be prejudiced, or sexist, or carry the beliefs within our historical moment, our research carries with it these biases. A good example of this is in how we have historically described sperm and eggs in scientific literature. Sperm are often described as “heroic” and eggs as “passive.” Anthropologist Emily Martin wrote an excellent article about this titled “The Egg and the Sperm: How Science Has Constructed a Romance Based on Stereotypical Male Female Roles”. Again, I want to emphasise that I believe in the power of science and evidence-based truths. However, the issue of gender identity isn’t a question in science; it is a topic that is cultural, social, and political.

h: To interpret a work of art, we must engage in a kind of empathetic dance with both the work and the artist. Beyond art, empathy is also essential to constructing and upholding social systems. Do you think art has a practical educational mission?

AL: I don’t think that art is required to have a practical educational mission, but art is always communicating. When people make art, their lived experiences are encapsulated in some way, no matter how abstract the artwork is. In this way, I agree that it is an empathetic dance. And this is such a nice way to envision it, because it requires more than one body — the maker and the viewer — and the liminal space of interpretation that gives the experience an exciting tension.

h: Your work draws together a unique aesthetic with technical expertise. Beauty seems to be an important means of communication in your work. Could you explain to us why this is?

AL: One of the ways I approach my practice is in imbuing thought into materiality. As an artist, I use different tools, materials, colours, and textures to encapsulate different ideas. I believe that aesthetic experiences communicate knowledge, similar to the way that papers and books communicate ideas; it is yet another language. Part of my practice is looking deeply. Perhaps the analogy through writing would be that if writers read a lot, as an artist, I am always looking.

h: The way we perceive and understand ourselves, and the identity that we project in consequence, structures much of our relationship with society. What is your current vision of yourself and how would you describe your mission?

AL: I am a thinker, an artist, a researcher, a maker, and a mother. I am a human with a uterus, which puts my body in a certain biopolitical field in the world. I tend to think with my hands, and I hope that the things I made and put into the world can spark contemplation.

h: Ethical norms reflect the society that created them. We live in a world composed of diverse social models, yet some art strives to develop a universal language and avoids local context. What does your audience look like?

AL: I hope that my work can reach diverse audiences! I believe those are the most fruitful conversations, when diverse bodies gather around a table to bring their own histories, their own truths, their own open minds. I believe great conversations can occur with art because it allows us to suspend our disbelief, our biases, our mundane routines, and our fears to open a different channel of communication and understanding.

h: Across time, science has pushed ethical boundaries through discoveries and technology that contradict accepted norms. If we consider scientific progress as something inevitable, then a conflict between science and society is inevitable too. Which side would you choose?

AL: I don’t believe that technological development itself has to be antagonistic. In many ways, we develop technologies to encapsulate our hopes and dreams too. We can develop and utilise technologies for health, mindfulness, empathy, and communication. We can also develop atom bombs, surveillance systems, bioweapons, and other intensely frightening things. Moreover, technologies developed for “good” can also enact harm when used with certain motivations. I think this is where a deeply interdisciplinary education is important; we want our engineers and CEOs to have taken classes in ethics, just as we want our government officials and voting bodies to be fluent in technological understanding.

h: Your work refers to various twentieth-century movements in art—Dadaism, surrealism, pop art, postmodernism—and to experiments in plastic arts during the same period. Are there thinkers and artists of this time that you would call your teachers?

AL: I don’t think of my work as belonging to any specific category or movement. However, I have admired many feminist artists, including Louise Bourgeois, Barbara Kruger, Guerrilla Girls, Pussy Riot, Martha Rosler, and many socially engaged artists, including Tania Bruguera, Krzysztof Wodiczko, and Mierle Laderman Ukeles. I have also been impacted by speculative design, and the writings of Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby.

Mind in the Machine, 2017

Photography courtesy of ANI LIU

Eyeris

Photography by HANG XU

Pregnancy menswear, 2020

Photography by HANNEKE WETZER

Kisses from the future

Photography courtesy of ANI LIU

h: It is widely believed that traditional ethics can only be applied to creatures of biological nature. Do you think the emergence of artificial intelligence (even hypothetically) or the creation of biomechanical systems will modify aesthetic norms?

AL: Actually, I remember a professor once told me that evolution has no ethics; that biology has no ethics. It is a reality of biophysics and evolutionary fitness. I think what he meant by this is that the lion does not consider any ethics when it comes to hunting down prey, just as the virus does not consider ethics when it infects a child. Hardware and software systems, on the other hand, are made by humans who are able to consider ethics, and this is something to be taken seriously by those who make these technologies. Artificial intelligence or machine learning, for instance, are trained on enormous data sets taken from reality, and as such, can absorb our own biases. Like us, algorithms can become sexist and racist, and it is of utmost importance that we continually address these issues.

h: Several decades ago, scientific and creative disciplines began to intersect more frequently. Through science, there are new ways of making art, new ways of thinking about art, and new forms that art can take. How does science benefit from art?

AL: I believe that artists contribute so much! When I was a child, I really enjoyed looking at the sketchbooks of Leonardo DaVinci at the library. I especially loved the drawings of speculative machines, the mechanisms, and studies of the body. I admired how drawing was a form of understanding, and the way that the unpacking of knowledge could occur through drawing. Today, most knowledge is built through collaborative endeavours. I believe that artists bring a lot to the table: a different way of approaching a problem, insights from different lived experiences, as well as the work of visualising abstract ideas.

h: Your works explore the sensual nature of a person and their body. At the same time, these works could be seen as a mirror of your experiences of love, confusion, and fear. Should an artist have boundaries between their personal life and their work? If so, why?

AL: I think each artist sets their own rules and boundaries regarding their practice. Some of the artists I admired a lot while studying as a young artist include Louise Bourgeois and Kiki Smith, who made intimate works that drew from their personal lived experiences. For me, the work that I make is true to the heart; in my studio I must be honest with myself, or it just doesn’t work. As such, for me the work is quite personal. The way these manifests can range from the conceptual seed or the materiality of the work, such as when I use sweat or breastmilk.

h: New social platforms, media, and virtual worlds are becoming not only an alternative means of communication, but also a new way of escaping reality. We can reinvent or even replicate ourselves there. How do you think this will affect the real world?

AL: I have had a long-standing interest in simulations — when does a representation of a reality surpass the “real”? Artists have always used signs and symbols to build representations, and now the toolset has become broader. I remember the first time I put on a development kit for a VR headset, it must have been almost a decade ago now. There was such a thrill to enter this immersive environment, yet I was also painfully self-conscious about the body I left behind in the room, ripe for voyeuristic consumption. There are well documented studies on the negative impacts of social media use on self-esteem, yet we continue to spend hours scrolling through our filtered feeds. In many ways, the speculation of how virtuality will affect the “real” world is no longer a speculation, it has already arrived.