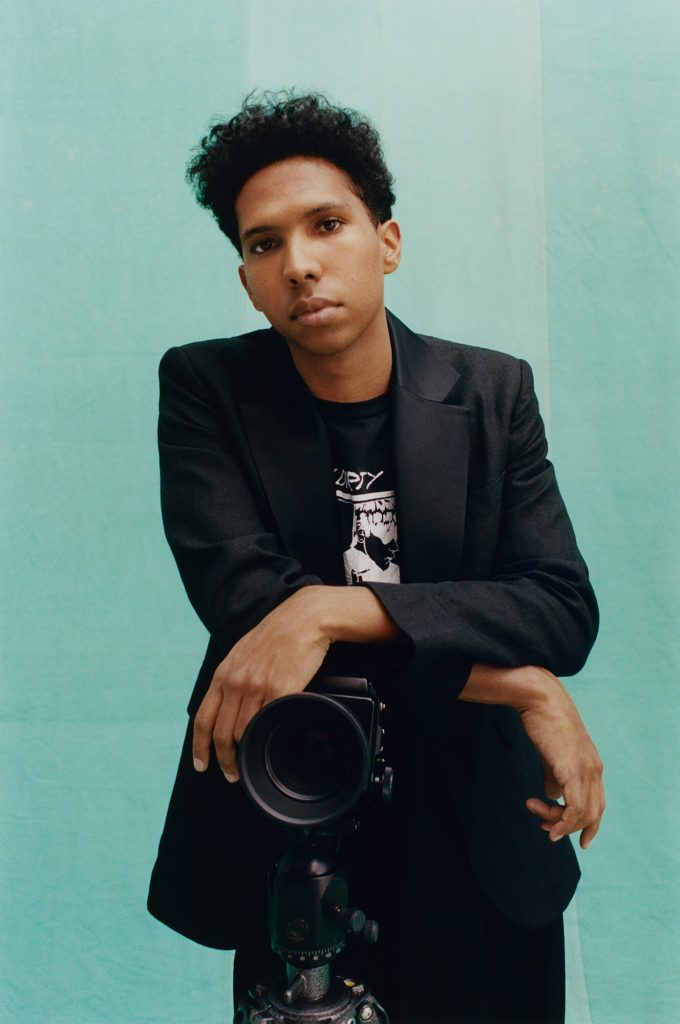

We don’t know where time begins and where it ends, but we can feel its moments, infinitely small and infinitely large. Perhaps therein lies the mystery of time, when a brief moment can tell a long story, and a photograph can create a world. Gazing at a snapshot, the emotional spaces of the author and the viewer merge. For each of us, this experience becomes personal. Today we invite you to delve into the story of Tyler Mitchell, a visionary photographer whose work has redefined the conventions of fashion and portrait photography.

Mitchell’s ability to infuse his photographs with emotion and authenticity is unparalleled, setting him apart as a true master of his craft. His commitment to representation and diversity in the industry serves as a beacon of inspiration for many, proving that talent knows no bounds and that art has the power to challenge and reshape societal norms. In an era where visual storytelling holds immense power, Mitchell stands as a trailblazer, using his lens to amplify voices, celebrate individuality, and inspire change.

hube: In arts, light, form, and colour are used to shape composition and create dramatic tension. What elements or aspects do you find most significant in your emotional interpretation of art?

Tyler Mitchell: I think the most important element for the perception or interpretation of creative work is the narrative behind it. It’s actually strange that I have a very defined answer to that question, because all parts are significant. But I think without narrative, without some sort of element of storytelling behind a piece of art, film, or photograph, you do not have much to hold on to. I think this is what makes something truly special. What’s the story of the person who made it? What’s the story being imbued into the object, the image, the photograph, or the film? And how does it move? And how does that start new conversations? I think without that, especially when it comes to contemporary photography, a beautiful image is not enough.

h: Is there a specific narrative that has really touched you?

TM: As much as I am an artist, I am equally an obsessive art viewer and movie watcher. Movies, more than anything, really speak to me. In film school, they taught us that there are essentially only seven stories to be told that are retold in different ways. So no single narrative affects me the most. When you see a familiar story told from a fresh perspective, or when a narrative is engaged from a genuine point of view, or when something comes from the heart, that is the type of sincerity that I’m looking for. You can’t replicate or fabricate that kind of sincerity in a narrative. You can always tell whether someone has lived through something.

As an artist born and raised in Atlanta, the geographical and historical context of the place plays a role in my work. I’ve been rewatching Atlanta, the TV show. It is hilarious, entertaining, and special because its creators are not just from Atlanta but are making art about the cultural specificity of being Black in Atlanta, and they only managed to create such a relatable show because it is a reflection of their lived experience. You can only make a TV show about being a traveling rap posse on tour in Europe from America if you’ve lived it.

That’s what I try to do with my art, I hope to create something that makes people feel connected.

h: It seems that your work is more focused on the inner world of a person than their external image. Even when you work with advertising, you tell a person’s story. Why is this important to you?

TM: Yesterday, I wrote down something that was quite amusing. While reading a review, I came across a quote discussing the unfashionable yet romantic notion that a common humanity unites us all.

The impetus behind many of my photographs originates from a genuine connection with the people I’m photographing. About 99% of my work revolves around portraiture. Some of it is created in the context of commissioned projects, often for magazines, which is how many people came to know my work. Additionally, a significant portion is personal work initiated under my own impetus to tell a story.

Regardless of the context, all my work has to be rooted in the somewhat trite and slightly cliché notion that I must genuinely feel connected to the subject matter in some autobiographical manner. So, yeah, I suppose you’re touching on the idea of a connection to the person in front of the camera, and that’s paramount in my work.

Self-portrait

Curtain Call, 2018