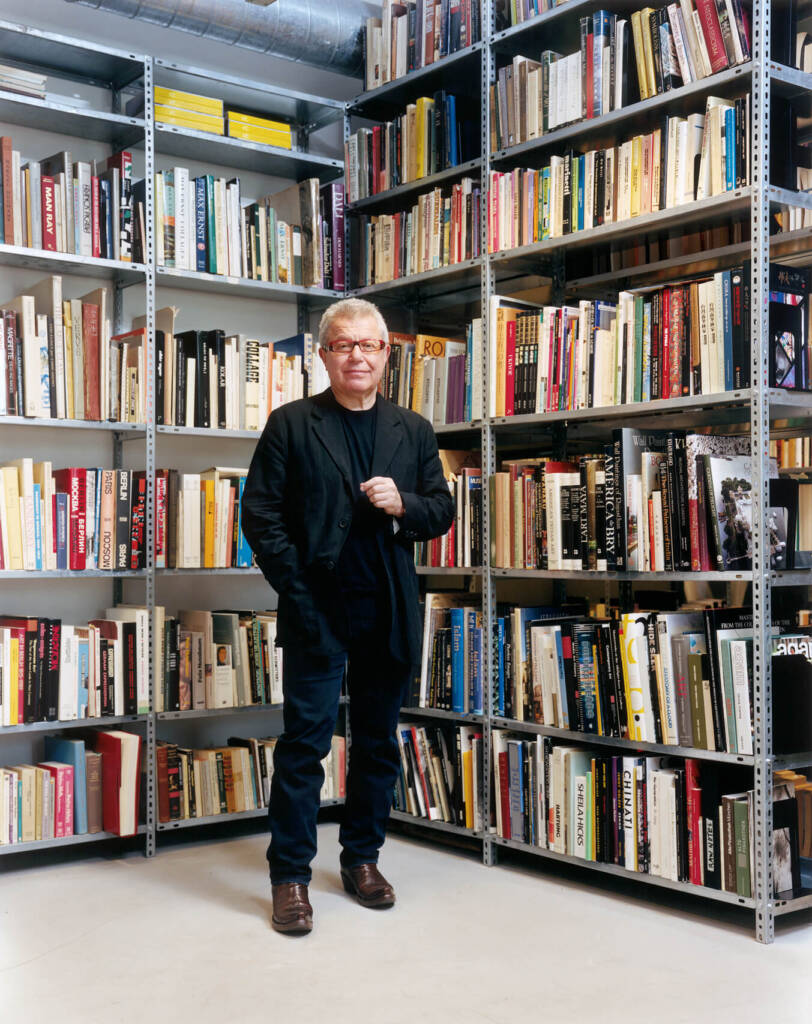

Photography by STEFAN RUIZ

Courtesy of STUDIO LIBESKIND

National Holocaust Monument I00

Ottawa, 2017

Photography by DOUBLESPACE, courtesy of STUDIO LIBESKIND

Daniel Libeskind, a celebrated architect known for his dynamic and expressive designs, draws inspiration from his diverse background, which spans from Poland to the United States.

His creations reflect a deep belief in the power of architecture to shape physical spaces and cultural narratives. Libeskind’s philosophy emphasises the importance of emotion alongside reason in design, aiming to evoke strong feelings while maintaining logical coherence. He pays close attention to the context of his projects, whether in natural landscapes or urban settings, striving to create buildings that resonate with their surroundings.

Among his most famous projects are the Jewish Museum in Berlin, renowned for its poignant exploration of Jewish history and identity, and the Frederic C. Hamilton Building at the Denver Art Museum, celebrated for its bold, angular design and innovative use of space. With an eye towards the future, Libeskind embraces new technologies, but his designs remain deeply connected to the human experience, ensuring a lasting impact across both the architectural and emotional realms.

In our interview with Daniel Libeskind, we explore movement in architecture, the tension between construction and deconstruction, and the power of emotion.

hube: Your architectural forms are always very dynamic. Movement, and therefore time, seem to be important components of your work. How do you perceive time and the future?

Daniel Libeskind: Things are changing every second. We are missing something stable. It’s hard to make predictions, but one thing is for sure, we see many technological forces that are very powerful, which are transforming architecture and reality. There are many political forces that are also threatening democratic states with aggressive agendas. So, yes, I believe we are living in an uncertain time.

h: Philosophy uses deconstruction to understand the place of humans in the world. How do you perceive this concept?

DL: Deconstruction is a very important philosophical movement in our time, much like existentialism was in the post-war era. But in my opinion, there is no direct connection between philosophy and architecture. This first became apparent in the famous debate between Albert Einstein and Henri Bergson in 1922 in Paris, where they talked about how philosophy affects everyday life and everyday thinking. There are, of course, many current analyses and analogies. The wording itself, honestly, is not good for architects because it suggests taking things apart, and architecture has always been about construction.

Construction and deconstruction are complicated ideas, and complicated for the public to understand, so l’d rather simply speak about the philosophy that underpins architecture in all its complexity throughout history.

h: Art seeks new ways of interacting with the material world. For architecture, this manifests as an intrusion into space. It seems that the idea is more important to you than the context. Is this so?

DL: Of course, the context is very import-ant, but we should not forget that by doing something, by acting in the world, we’re also transforming the context. So it’s not just putting something in an inert, neutralised space. Through the act of creation, we are thoroughly transforming history itself. That is part of the dynamism, the dialectic between site and insight.

h: Your drawings seem to be a collision between the flat plane of the sheet and geometric elements. They are very expressive, like your ideas. How do you balance the emotional and rational in your work?

DL: Architecture is a rational process. In order to build anything, you need reason, you need causality. But, certainly, architecture without emotion would be meaningless. The way a piece of literature, a piece of music, or a film would be completely meaningless without emotion. Emotion is as important to architecture as reason. And of course, being reasonable includes admitting that emotion is a dimension of architecture.