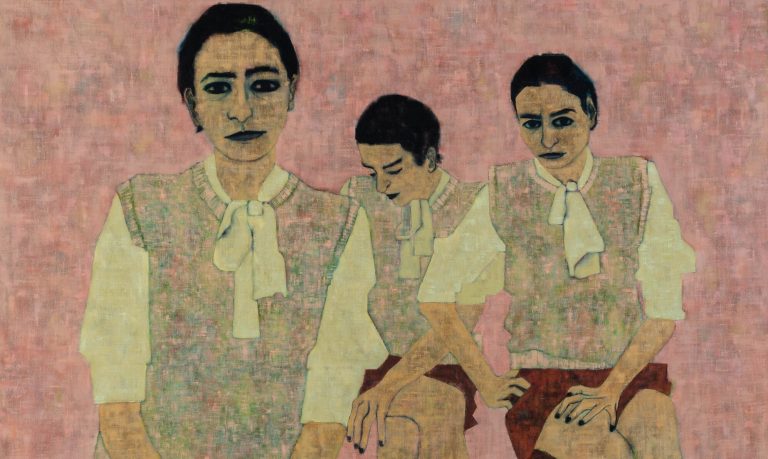

Askew, 2023

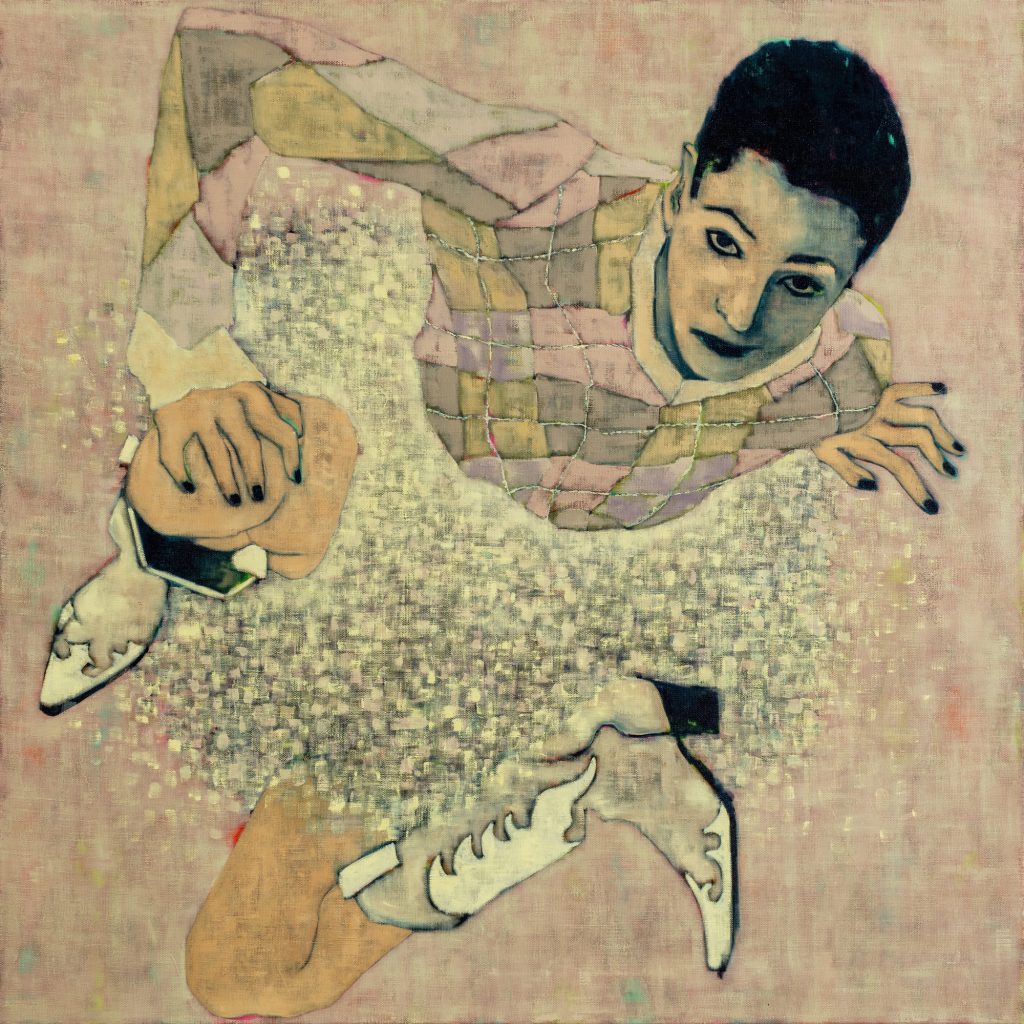

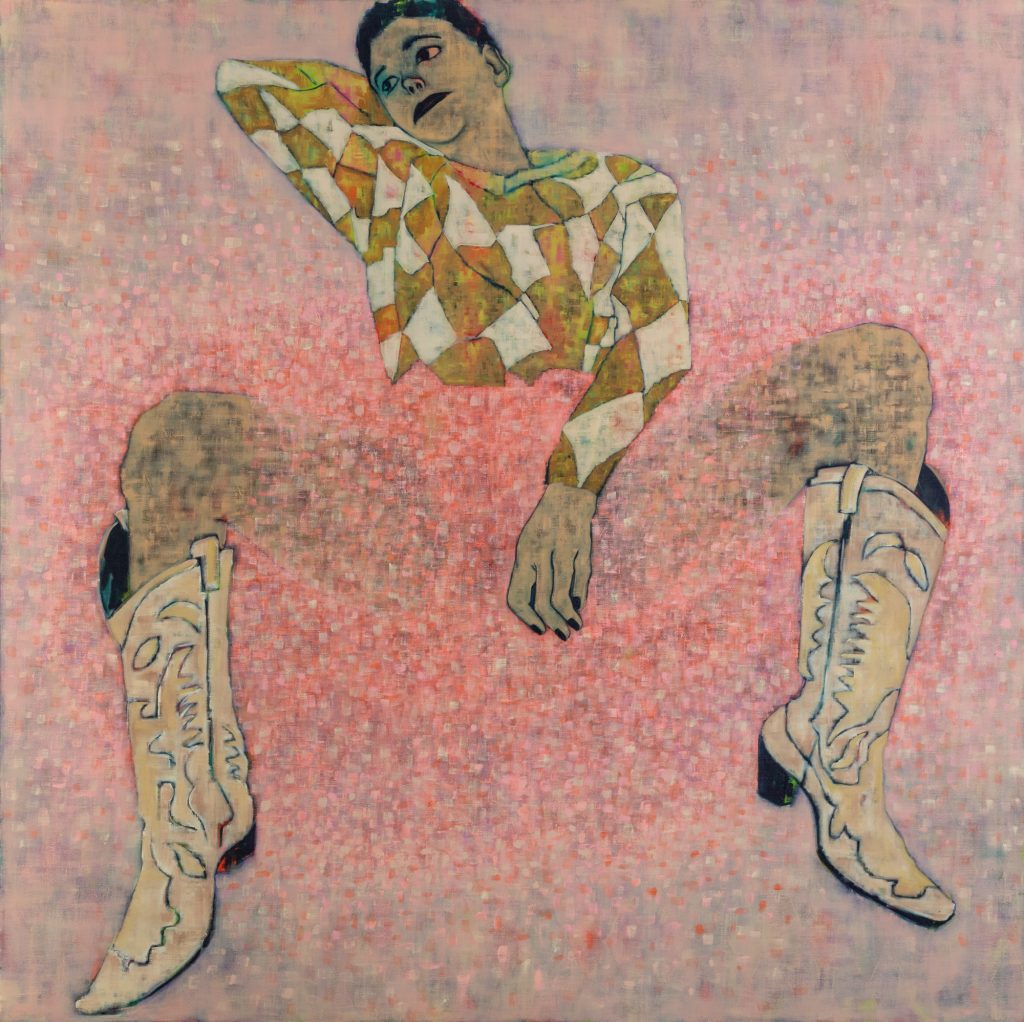

Afterglow, 2023

Sara Berman’s genius is a conversation between painting and textiles. Exploring the uncomfortable nuances of the female bodily experience, her works invite the audience to observe the point where art and identity collide. Here clothing transforms beyond mere fabric, blurring the boundaries between inside and outside.

hube: How did you first discover and become interested in the Harlequin character, and what drew you to incorporate it into your artistic practice?

Sara Berman: The Harlequin character came about quite soon after I graduated from Slade. Throughout my whole time at Slade, I was quite careful to avoid the use of clothing in my work because, as a fashion designer, I was aware of its importance. I didn’t want to take that lightly. With that sort of responsibility, I just decided to avoid it altogether.

This wasn’t really an issue in the development of my work until I had my first solo show in Hong Kong; I suddenly realised that I wasn’t comfortable with the nudity of my women, I did not understand why they had to be nude. I became uncertain of what my intention was. Later in New York, I saw Picasso’s Harlequin. This interested me. I thought to myself: “What an interesting costume!”

I did some research into the topic of Harlequins and found out that, when played by a man, the Harlequin is actually an Arlecchino — a joker, a lovable rogue, a buffoon with a lot of agency. When played by a woman though, — which would happen rarely — the Harlequin stands as Arlecchino’s mistress, a sort of an adjunct to him. More rarely, a woman unconnected to Arleccino but a woman nonetheless. And this character is always a Trickster W*ore with the voice of a Harpy and no agency whatsoever.

This really interested me. I slowly began playing with this as a costume — my women, literally clothed as the Harlequin. As time’s gone on, this shifted into more of an abstraction and became a part of the foundation of the painting.

h: At Armory 2022, you showcased the video “Trickster W*ore,” created in collaboration with Anthony Byrne, among other video works in your portfolio. Could you elaborate on your experience as a performer embodying the Harlequin character directly on camera?

SB: The first time I attempted to do it consciously I worked with a brilliant choreographer Theo Koppel. We worked for six months to develop a language and movement around Arlecchino. But when the time to film came, I ended up totally jettisoning the routine we had developed and instead operating with the intention of those movements. It ended up being a very free form, a session where Anthony and I decided to connect very deeply and work together almost through the exclusion of everything else. It ended up being a night of free dance expression and movement, which I think in the end felt right for where the character was in my mind at that time.

I have become aware of how important my politics are in my work. Obviously, they have always been there. It’s impossible to ignore that but it feels particularly strong and critically important at the moment. I’m thinking really carefully about how I use myself, paint myself, and acknowledge that I am in fact working as a performance artist within painting. I think I’m aware of myself as a sort of abstract objectification. And that becomes performative.