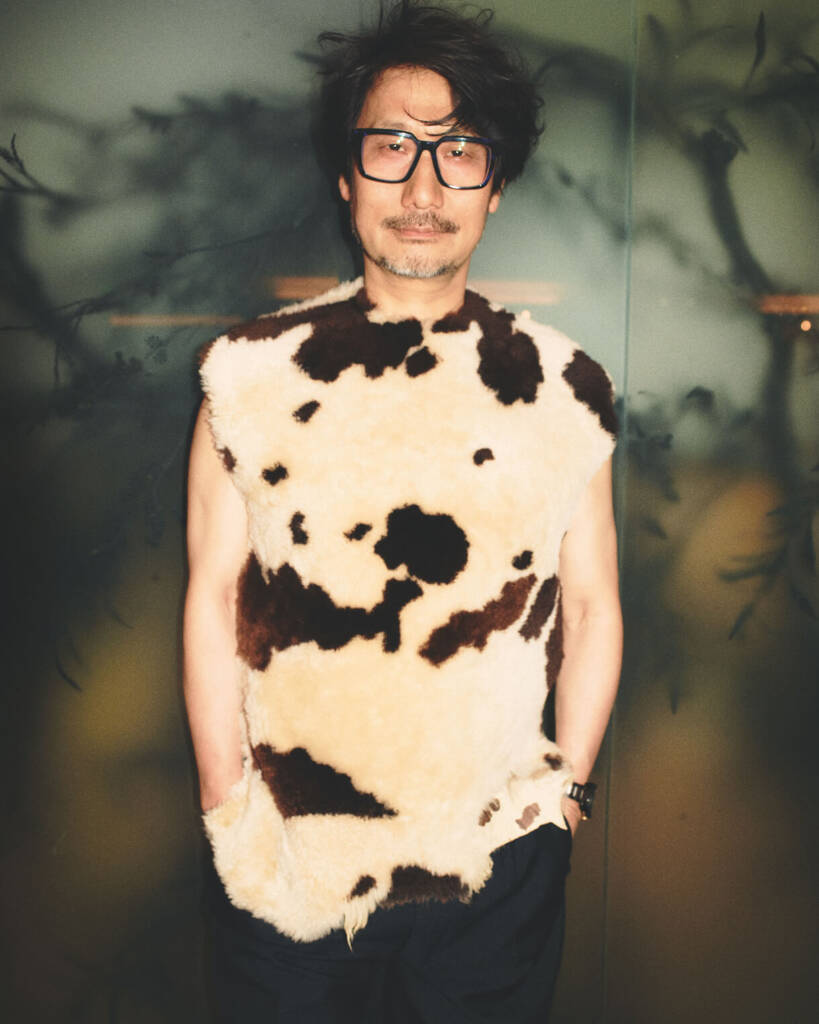

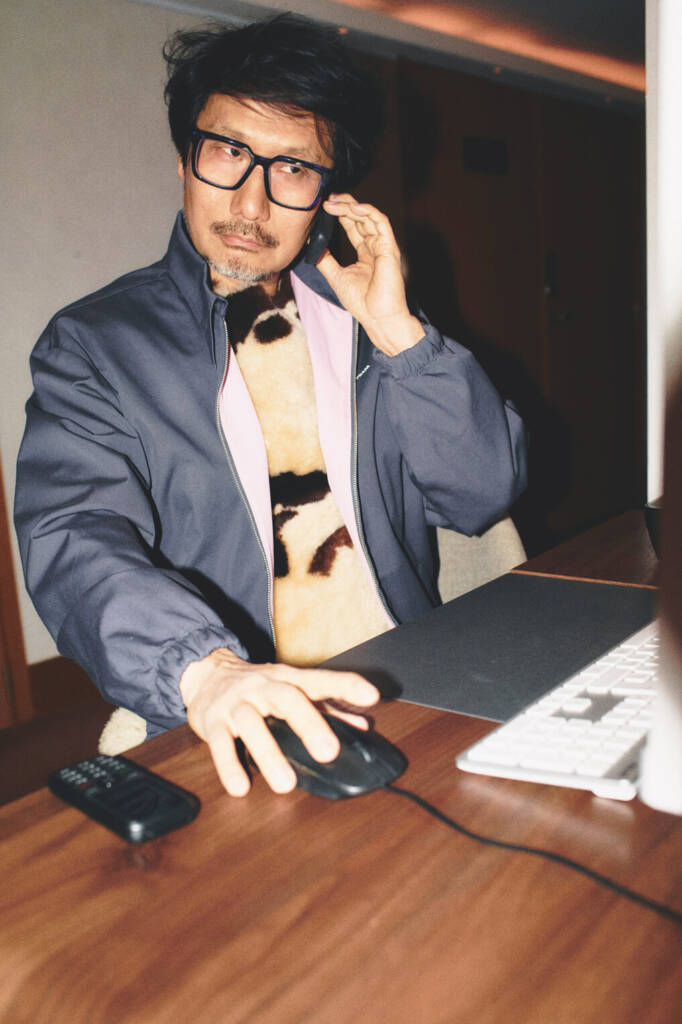

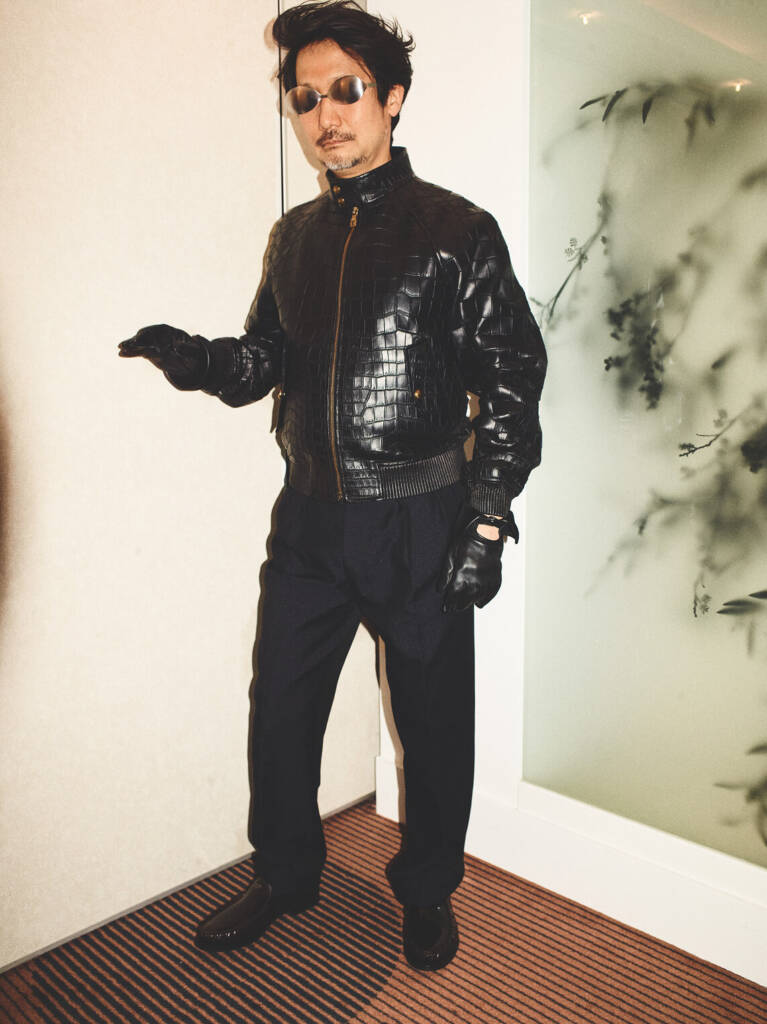

Since the release of the acclaimed Metal Gear in 1987, Hideo Kojima has been more than just a game designer. Dubbed the father of the stealth genre and considered the first gaming auteur, his strange stylistic choices and in-depth storylines have consistently pushed the boundaries of an industry caught in a commercially-driven orbit.

In 2015, he broke away from the Konami Group to form Kojima Productions, giving us Death Stranding—a game that polarised, mesmerised, and is now being adapted for the screen by A24. Its sequel, Death Stranding 2: On the Beach, is set to drop later this year, and is already one of the most anticipated releases of the decade. Slow-paced, emotionally dense, and hauntingly designed, it’s everything Kojima is known for—allowing for the kind of deep thematic development that earned him the 2020 BAFTA Fellowship.

Fresh off Satellites, an installation at Fondazione Prada in collaboration with Danish director Nicolas Winding Refn, and ahead of what may be his most expansive year yet, we spoke with Kojima about GenAI, authorship, and the blurred line between the real and the rendered.

hube: One day, humans may lose the ability to distinguish between reality and illusion. Does this present more opportunities or dangers?

Hideo Kojima: Being able to simulate a variety of life experiences—regardless of physical disabilities, limitations, or individual health conditions—is a remarkable advancement. It allows people to have immersive and adventurous experiences without physical risk. This technology can also be applied to simulations, training, and education. Rejecting such advancements would set back human progress. Nevertheless, there must always be clear safeguards and rules to distinguish between reality and virtual reality. The human brain is highly adaptable: it can alter memories, turn imagination into perceived reality, and even reshape actual experiences. We must find ways to regulate this and ensure that individuals and society as a whole can differentiate between what is real and what is an illusion. If the necessary technologies and legal frameworks are not in place, then these advancements should not be made widely accessible.

h: In the world of video games, time follows its own unique rules. A player gains experience but can always start over. Is this something we will ever be able to replicate in real life? Do we truly learn from our mistakes in a game, or are we just learning to optimise our strategies and outcomes?

HK: In real life, there are no do-overs after death. This concept exists only within games. It originates from an old practice, dating back to arcade games half a century ago, where players were given a few minutes of playtime per coin. The “Game Over” and “Continue” mechanics were designed to keep players spending money within a limited time frame. In Death Stranding, Sam’s role as a repatriate was conceived as a kind of ironic take on this convention.

The meaning of “Continue” in games changes depending on whether we see it as simply retrying after a failed choice or as learning through virtual training. For example, in command-based adventure games, a player’s failure is merely a wrong choice. Continuing allows the player to select a different option and then progress. However, since the game follows a predetermined path set by the designer, the experience gained here has little relevance to real life.

In comparison, continuing in action games is similar to high jump in track and field. You attempt to clear a certain height, fail, and then try again. Through this process, the player gradually improves and eventually succeeds. Once they clear that height, a higher challenge appears. This is the structure of action games and their continue system. It is not simply a matter of retrying after failure, but rather a form of training and learning.

h: With the rise of GenAI, the creation of self-evolving virtual worlds is becoming increasingly possible. How do you think this could impact the games industry?

HK: Humanity will not abandon AI as a tool. There are countless fields where AI has proven itself very effective: medicine, education, AI management, AI butlers, and AI counselling, to name a few. But what happens when it comes to art and creativity? AI requires an enormous database to make judgments. It can only process, refine, and organise what already exists. In terms of creative work, it’s what you’d call a “second brew” or a rehashing of creation. Things like formulaic Hollywood blockbusters, sequels, remakes, derivative works, or even mimicking the style of former works by someone who has passed away—these are within the realm of possibility for AI, but creating something that no one has ever imagined before, works for which no reference data exists, is something AI cannot achieve. At least, not yet. Perhaps 50 years from now, such capabilities will emerge. But for us, right now, our role is to compete with AI. To create things AI cannot think of, to accomplish what AI cannot do—that is the challenge humanity must take on for the future. Let AI handle what it does best. Just as labour was entrusted to machines during the Industrial Revolution, AI can assume its own tasks now. This principle applies to more than just creative work, it spans every field. Think of it as a mode in a racing game, where you compete against a “ghost” of your past performance data. That’s what this dynamic feels like. Humans must move ahead by recording data that AI doesn’t yet possess. Then, AI will inevitably absorb that data and follow in our tracks. Within this environment, humanity should continue to evolve. Even in medicine, AI can reference a vast database of patient information and predict the likelihood of illnesses by identifying probable diagnoses. Yet, as it stands, AI cannot treat those illnesses. Searching for what AI cannot do—that will become humanity’s purpose.

h: A crucial part of your work is the creation of new aesthetic forms. How do you perceive your relationship with artistic traditions of the past?

HK: The output of my creativity is produced using cutting-edge digital technology. However, traditional arts, culture, customs, and a variety of analogue forms of entertainment are what shaped me as a person. Films, novels, paintings, sculptures, contemporary art, theatre, music, history, comedy—all of these have shaped who I am. I watch one film every day. I read 150 novels a year. I listen to music daily. Every weekend, I visit art and history museums. I also go to live performances to see the bands I love. Whether it’s travelling or simply wandering, nearly all of my experiences are analogue. Growing up, there were no video games. So I’ve taken these experiences, these “memes” that I absorbed in the real world, and have converted them into digital expressions.

Today’s game creators absorb content that has already been converted into digital formats by someone else and then refine, develop, and improve upon it within themselves. That’s a generational difference. When analogue materials are compressed into digital formats by someone else, the brilliance and depth inherent to true art are diminished. Experiencing the genuine, unaltered form is essential. This is where creators of the game generation—those who grew up in an environment where games already existed—are at a disadvantage.

Famed Japanese manga artists (like Osamu Tezuka and Katsuhiro Otomo) revolutionised manga because they grew up watching films. They drew films in their manga. The same goes for anime director Mamoru Oshii—he grew up with European art films and created films within the medium of anime. However, the followers of Tezuka, Otomo, and Oshii inherited their memes exclusively from their works. If you create manga only from manga or create anime only from anime, your work will not give rise to anything truly new. As for myself, I create films and art within the medium of games. This is not a conscious choice, it is simply an inevitable result.