Gent-based publisher Art Paper Editions isn’t just making books—it’s reshaping how we move through them. At the helm is Jurgen Maelfeyt, who’s been at the forefront of the imprint for over a decade, quietly blurring the lines between editor, curator, and artist. His approach is rooted in conversation, often paring down thousands of images into a tactile narrative that feels more like a collaboration than a product. Think less “coffee table,” more “field notes from the inside.” Whether working on the ongoing Monogram zine series or dashing between international book fairs, Maelfeyt rarely sits still. In this interview, we speak about the in-between moments, the art of not starting at the beginning, and why traditional formats might just be the least interesting part of publishing.

hube: You launched Art Paper back in 2010, tentatively at first. What were those early years like? What does it take to build a publishing house from scratch?

Jurgen Maelfeyt: I started out making my own zines. Then one of my clients—someone I was making a book with—asked if they could put my name down as the publisher. That’s when I decided, almost overnight, to start a publishing house. That became Art Paper Editions. In the beginning, I thought I’d publish maybe two or three books a year—mostly my own work, and perhaps something from someone else. But I got into the book fair scene pretty quickly. That same year, I was invited to the first Offprint in Paris, and from there, I realized how enjoyable it was to make books. We started doing more fairs and traveling to other cities. About two years later, we went to New York for the first time. That trip changed things. From that moment on, I began to think of Art Paper Editions as something bigger. We got international distribution and I started to learn more about how book distribution works. Over time, I decided to split up the distribution—now we work with around eight different distributors in various countries. I think it’s important to have local representation in key countries because those people know the bookshops best. At a certain point, publishing and distributing books became the main part of my practice. After all, it doesn’t make sense to make books that no one can buy.

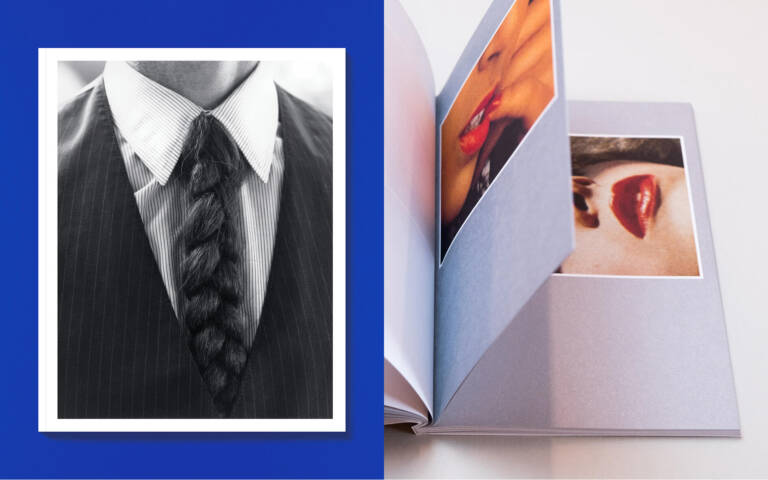

h: If someone had never heard of APE, how would you describe it now—fifteen years on?

JM: APE is an independent publishing house focused on photography and design with a bold visual identity.

h: The Monogram series has become a bit of a signature for you. What does it mean for an artist to have a “Monogram”? How do you strike that balance between their visual language and your curatorial voice?

JM: I started Monogram because I felt there was a gap between the thing that I started with APE, which was making zines, and what APE was at that moment a few years ago, which was mainly focused on making artbooks, and those books were becoming bigger and bigger. So I felt the need to do something more fast-paced. And I don’t like coffee table books anyway.

h: When someone comes to you with a body of work, a collection of photographs or an idea—what pulls you in? What makes you say yes?

JM: Most projects come from people I meet or have conversations with. The most important question I always ask myself is: can I make a book out of this body of work? Sometimes we even talk a few times before I start on the project. For example, with Paul Kooiker we spoke for a year about what kind of book we’d be making before I sat behind a computer and started the edit or design. Of course, I also receive a lot of submissions by mail—people often send me already designed books. But I prefer when they just send images, so I can imagine the book myself. What gets selected from there is very subjective. There’s no fixed rule, but I have to see if it feels right for Art Paper Editions. That’s really what it comes down to.