From the hand-drawn lines of his studio to the polished brass rails of a reborn Orient Express, Maxime d’Agneac marries reverence for the past with an unflinching drive toward the future. Over forty years, he’s honed a practice that treats every project as both a fight and a romance – where the discipline of his daily martial-arts training fuels negotiations with engineers and artisans, and where each material choice and beam of light becomes a narrative in miniature. Now, Maxime d’Agneac invites us into his world: one where the golden ratio holds more sway than passing trends, where true luxury is measured in patience and rarefied detail, and where the soul of a space is as carefully drawn as its blueprint.

hube: Your reimagining of the Orient Express interiors isn’t just about luxury – it’s a full-blown reinvention of a legend. What was the spark that led you to translate the myth of the Orient Express into a 21st-century work of art, and how do you balance heritage with futuristic innovation?

Maxime d’Angeac: Everything was already in the DNA of the Orient Express. I put myself in the same conditions as in 1920 – drawing by hand, no computers, respecting the simple laws of the train. If you make a mistake on a train, you break your toes or hurt your head; you must always have the right answer. Rather than chasing trends – ‘let’s use this fabric because it’s in fashion’ – we asked: What could the Orient Express be, 100 years later, with today’s techniques and top craftsmen in wood, iron, glass and fabrics? The spark was eternal: I’ve been absorbing early 20th-century art, architecture, literature, music since I was eighteen, and the Orient Express was in the very middle of that world, almost the apotheosis of its generation. I just went through every detail, as they drew the ‘matrix of everything’ back then, so I did the same.

h: You famously describe your work as a mix of ‘combat and romance,’ even crediting your krav-maga training as part of your creative arsenal. How does this duality manifest in your designs, and what does it reveal about your approach to architecture?

MdA: A project is always a fight – against time, budgets, clients, technical problems. It’s never a path strewn with roses. You must defend your idea fiercely so it isn’t diluted by others’ constraints. I train every day in MMA and Krav Maga; it’s meditation and concentration. That energy helps me negotiate with engineers, firefighters, pillow-sewing craftsmen – all at once. After the fight, I find calm, then dive back in. It’s yin and yang: you need equal measures of strength and seduction, of standing your ground and listening. Without that mental steel, technique, and talent alone won’t carry you to the finish line.

h: In an industry obsessed with trends, you remain steadfast to the ideals of the Italian Renaissance and Palladian proportions. What draws you to these classical principles, and how do they inform your modern projects, be it a private residence or a technical restoration?

MdA: Proportion and rhythm aren’t fashion – they’re truths. You either get them or you don’t. Trends are fragile; what’s in today is out tomorrow. Think of William Bouguereau – he was a 19th-century ‘superstar’ painter whose classical subjects fell out of favour. Who remembers him now? I’d rather wait in the wings for my time to come. Proportion, the golden ratio, Palladian harmony – they transcend eras. They give projects a timeless foundation, whether it’s a private residence or a train car.

h: Every screw, every custom-made piece on your projects tells a story – from the meticulously crafted suites of the Orient Express to the minimalist manifesto of Cube. How do you ensure that each detail contributes to a coherent narrative without overwhelming the overall design?

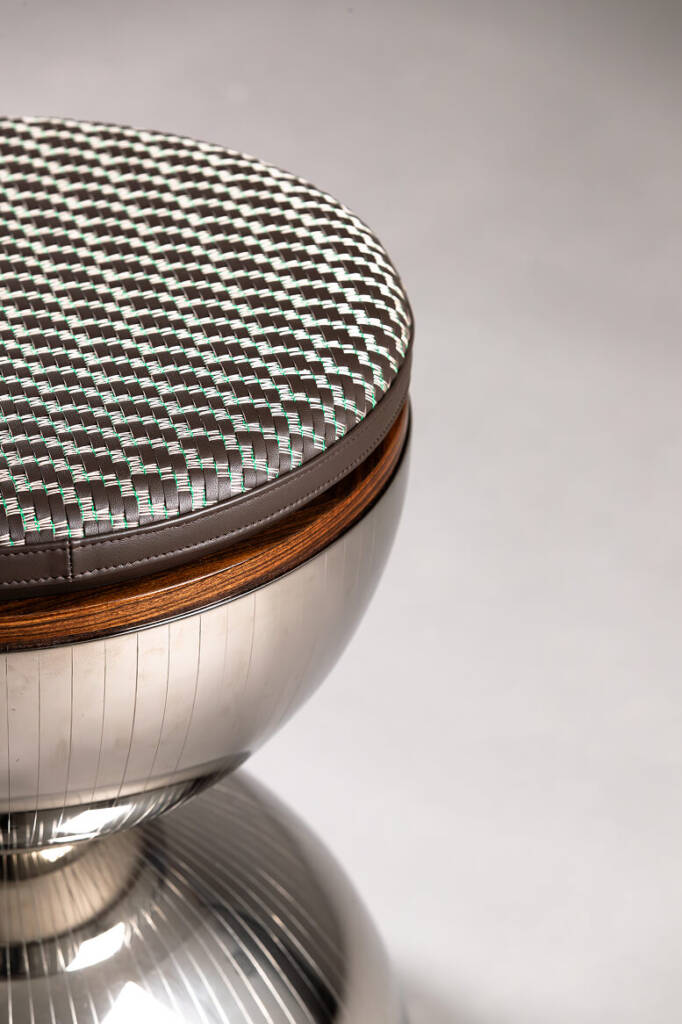

MdA: I treat details like a cake: too many layers and it feels heavy. You must distil the essence. Each drawing goes through endless doubt until it’s exactly right. Then I sit down with the craftsmen – like woodworkers and ironsmiths – to refine it further. Even the screw head can become an element of beauty. We speak the same language, but every detail is important; the devil is in the details. Whether it’s a richly ornate Express interior or a flat, weightless Cube, you must map every millimetre of wall and function. I’ve talked to master artisans since I was young – I know enough of each craft to collaborate intelligently.

h: Do you have a favourite material?

MdA: I love real, long-lasting materials – stone, concrete, glass. I avoid plastics like PVC, which pollute and age poorly. Good stone, well-drawn concrete (think Tadao Ando), refined glass – when placed rightly, these materials endure and tell their own story.

h: Your work places a singular emphasis on perfect volumetry and the interplay of light, transforming spaces into immersive living environments. Could you describe a moment or a project where light was the protagonist, redefining the space’s identity?

MdA: Light is always complicated, because it’s deeply personal and climate-dependent. Some clients crave brilliant daylight; others need cool darkness. Then there’s technology: gaslight, early yellow electric bulbs, today’s LEDs – all have different colour temperatures and behaviours. On the Orient Express, we chased the century-old glow with modern techniques, tuning reflection and shadow. Every window’s size, position and rhythm must be negotiated with the site, the facade, interior volumes. It never gets easy – but it’s what I live for.

h: With projects for icons like Guerlain and ambitious ventures such as the modern Orient Express, you’re redefining what luxury means in architecture. What do you see as the key challenges for luxury design today, and how do you respond to them in your work?

MdA: Luxury today is misunderstood as gold and bling. True luxury is rare, precious and takes time. You can’t rush luxury – it must be defined, crafted, prototyped. A tiny detail – like a Hermès buckle with a unique serial number – can cost little yet be utterly luxurious. Explaining that ‘time is money’ to clients is the hardest part. But without patient iteration – without prototypes and mistakes – you won’t reach that rarefied level.

h: After three decades in a rapidly evolving field, how do you see the role of the architect changing in the modern era? What advice would you offer young architects striving to balance technological advances with timeless design principles?

MdA: I’m hesitant to give advice because I learned slowly, by drawing endlessly, reading, travelling, accumulating my own library of references. Young architects must cultivate difference – become like fine wine. You can’t conduct a 100-piece orchestra on day one. Computer design tools are miracles compared to my early career, but you still need hands-on experience with craftspeople before they vanish. Study the Renaissance masters, talk to structural engineers and stonecutters, then trust your ideas. Clients come for your vision – that’s your true value.

h: So architecture is for those who are patient?

MdA: Absolutely. You’re in a two-and-a-half-year battle – like designing a ship or a train with thousands of stakeholders. You must be ready, every day. Travel feeds me: seeing old and new structures, landscapes – it’s endless inspiration that reminds me, ‘I have work to do’.

h: Finally, how is architecture connected to emotion, and what feelings do you aim to evoke in the people who experience your spaces?

MdA: Architecture is poetry. If your building moves someone – reveals a new perspective, frames a view, evokes calm or mystery – you’ve succeeded. No emotion, no project. I frame each door, each corridor, to provoke a moment – never overwhelming, but always meaningful. A client in Geneva told me my house felt unlike any other: the volumetry, the perspective – it surprised him every day. That quiet astonishment, that spark of delight, is what I build toward.

Photography courtesy of MAXIME D’ANGEAC