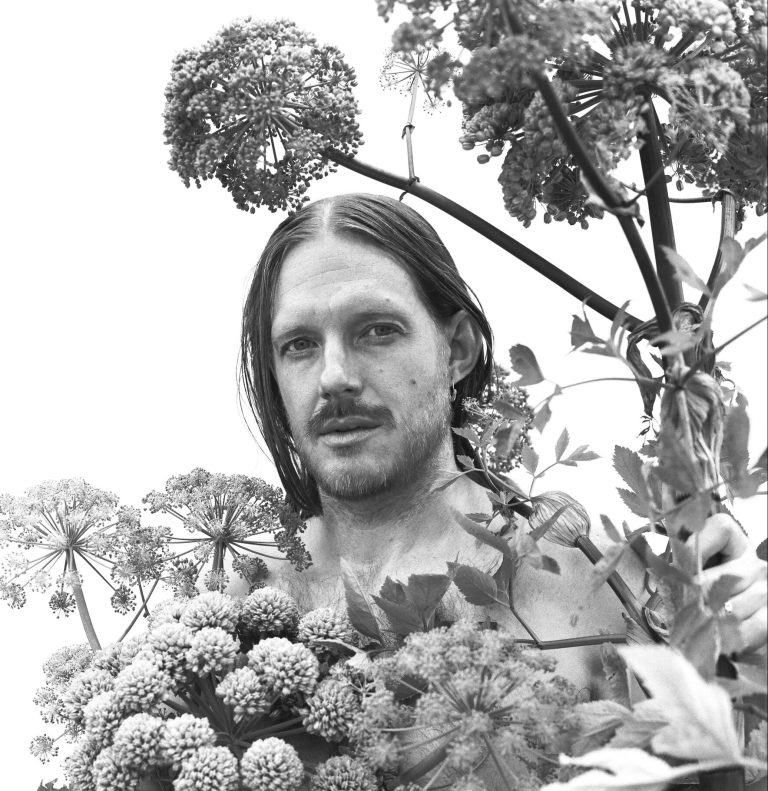

Alopex Mask

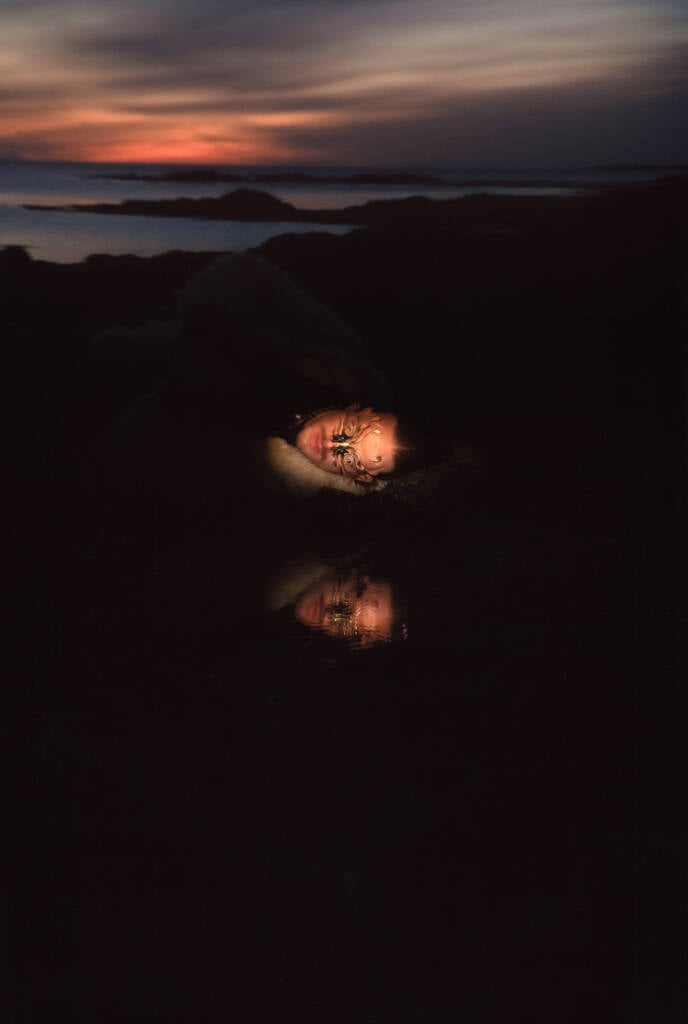

Renowned for his hand-embroidery and mask-making, the Iceland-based artist James Merry has frequently collaborated with Björk as a co-creative director on her visual output and has workedwith institutions and individuals such as the V&A, Gucci, Tilda Swinton, and Iris Van Herpen. Drawing inspiration from the ever-changing qualities of the natural world, Merry’s work explores the interconnectedness of humans and nature. We met to explore how the meditative process of embroidery alters realities and how masks can offer deeper insight into identity and personality.

hube: Humans have long viewed the natural world as more than a physical realm. Across time, engaging in dialogue with nature has been associated with the idea of connecting with eternity; of establishing a relationship with something greater and more profound than one’s self. What are your thoughts on this?

James Merry: I think my connection with nature is not so much about the eternal, it’s more about trying to integrate the human back into nature, placing us inside of it rather than above or outside of it. I have always been fascinated by artefacts and forms that somehow exist between human and animal, animal and flower, etc. A lot of my favourite works of art exist in those ambiguous spaces between identification or classification. So when I do reach out for a conscious connection with nature, it isn’t so much a sense of timelessness that I am looking for, but actually the opposite: I tend to fixate more on the ever-changing, mutable qualities of the natural world—the cyclical, evolutionary, or metamorphic aspects. I like observing how things mutate, how things decay. Perhaps for me, integrating these natural elements into my work is more about getting close to the spirit or essence of a thing and attempting some sort of delicate merge with it.

h: Masks are often associated with transformation and mysticism. Aside from altering our appearance, they can also affect our inner world. Do you think about this when you’re creating your masks? And do you think a mask can exist without a person?

JM: I usually try to turn off the analytical part of my brain while I’m creating a mask, I prefer to let my hands and eyes do the thinking. Afterwards, I will begin to decipher what has emerged and will try to figure out where it came from. A few of my recent masks were made differently, I went into the studio with a more conscious intention. With the Alopex masks I was very consciously trying to create an arctic fox character. But that was a very unusual approach for me, I don’t normally have a clear reference in mind when working, I just see what emerges.

Whether a mask can exist without a person is a very interesting question, one that could take me a lifetime to answer. I have been bumping up against it a lot recently when exhibiting my pieces in museums. Some of my masks seem to work really well when displayed alone as an object, while others can’t seem to access their power without a human face behind them. I think this is exacerbated by the fact that I design a lot of my masks to look like they are growing out of the face, rather than being placed onto it, so having them exist alone feels a little like uprooting a plant from its soil.