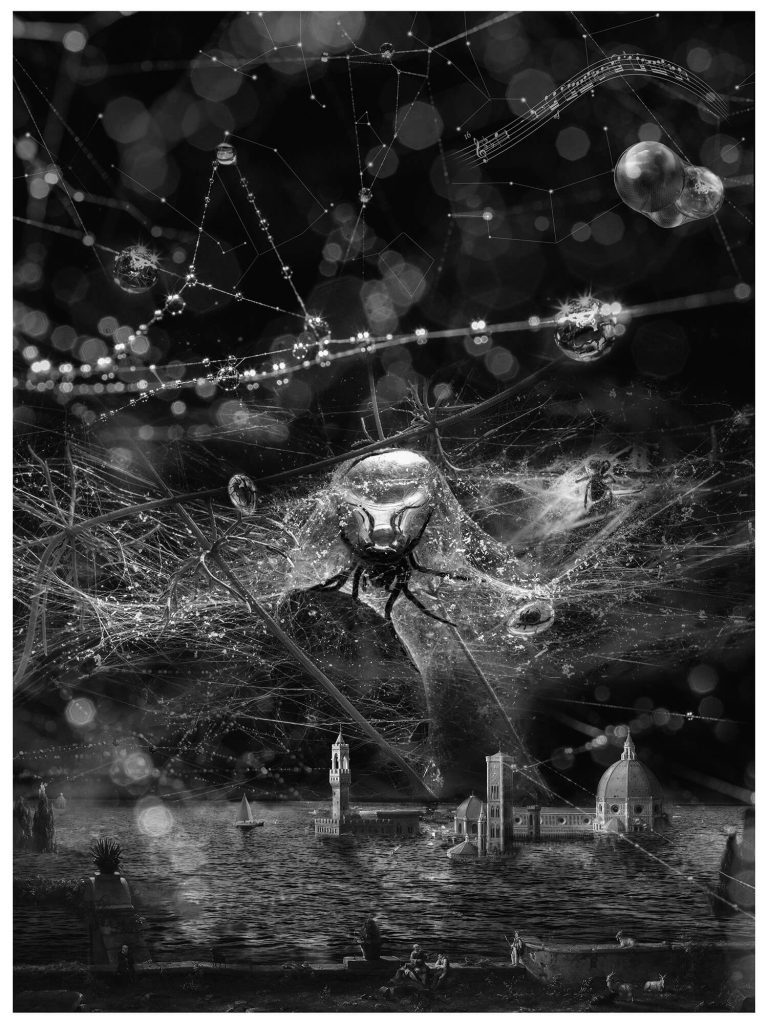

Aria, 2020

Photography by STUDIO TOMÁS SARACENO

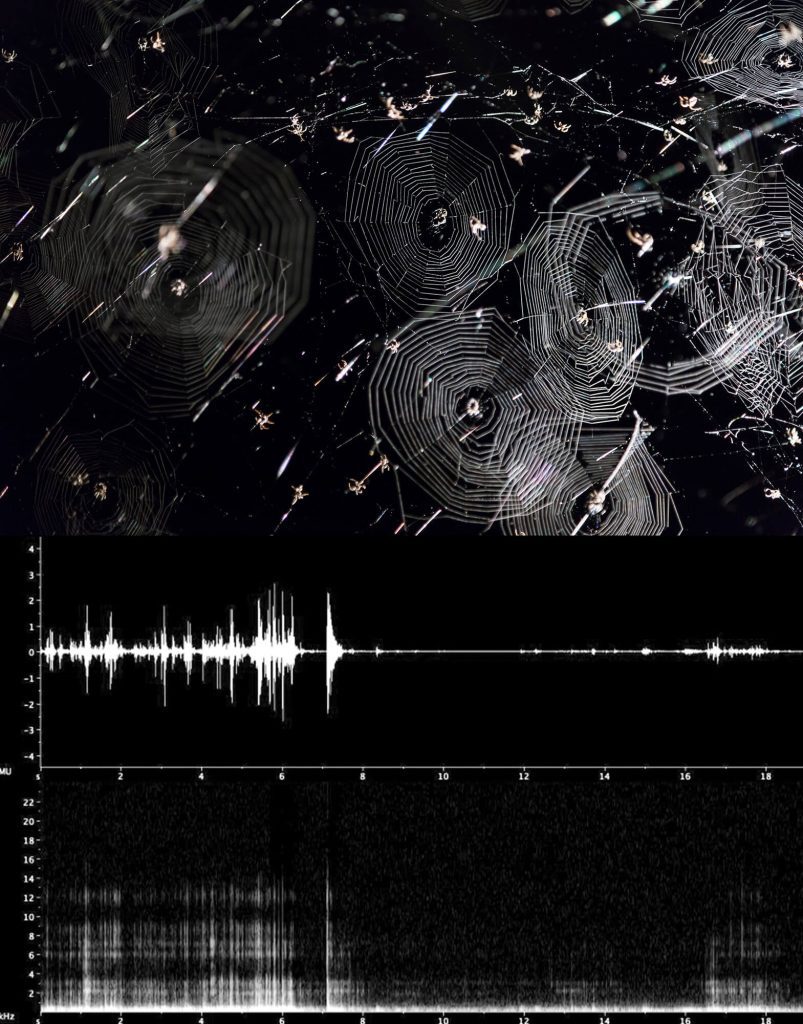

Quasi-Social Musical Instrument IC 342 Built by 7000 Parawixia Bistriata – Six Months, 2016

Installation view, How To Entangle The Universe In A Spider Web, Museo Moderno, Buenos Aires, 2017

While art and science are often considered as disciplines in strict opposition, in the practice of Argentinian artist and trained architect Tomás Saraceno, they coalesce and intertwine. Across a growing body of work focused on aerosolar sculptures and spiders and their webs, Saraceno explores environmental consciousness as a means of understanding space and connectivity.

What defines our human connection to the world? How do our actions shape it, and what responsibility do we bear in caring for it? Saraceno endeavours to answer these questions through research-based experiential works that are ethereal and architectural, natural and manmade, interactive and immersive. Together with his interdisciplinary studio, he explores themes of social cohesion, ecological awareness, and scientific innovation, urging us to reconsider what truly matters from a novel and thought-provoking perspective.

hube: Your projects unite artists, scientists, philosophers, and engineers, bringing together scientific and artistic explorations of the world. And yet, the duality between the domains of science and art perseveres. What are your thoughts on this enduring distinction, and do you believe it’s fair?

Tomás Saraceno: The name that immediately comes to mind is Arturo Escobar, a brilliant anthropologist who wrote this beautiful book, Designs for the Pluriverse, that weaves together an ontological proposal of many interdependent worlds, perspectives, and imaginaries. The mindset of some people is often too confined: they think within the framework of polarities and dualities. It takes a lot of time and work to change such a way of thinking and start seeing that all things in the world are connected much more tightly than we used to think. It seems that sometimes only scientific methods allow us to understand reality in view of the crises we are facing. Art, at times, is instrumentalised to help aestheticise what science reveals or suggests about the world. I don’t think that their division will really help to fully engage the sociopolitical climate faced today. They are probably deeply rooted in a particular way of thinking, of disciplining domains of knowledge. I come from Argentina, and there are many other cultures that have a very different understanding of their participation in life on this planet. Their cosmovision and perception of reality has persevered distinctly from the Western tradition for millennia.

h: In your work, the spider’s web strikes us as a motif for the interconnectedness of all things in our world, emphasising each person’s role and responsibility in everything that unfolds. Do you see humans positioned at the centre of this web?

TS: I’ve always been fascinated by spider webs, and I find most compelling the fact that many spider webs don’t have a centre. The web you most likely have in mind is an orbicular web, where radiuses connect in the centre and orbs extend around, but that’s only one type of web. There are many, many other types of spider web geometry. The webs I’m most fascinated with are those woven by social spiders. There are 47,000 spider species, and only about 10 of them are social spiders. A social spider usually creates a web that doesn’t have a centre. It is very decentralised and much larger than solitary spiders’ webs which sometimes have centres, too. If you try to disentangle them, there might be many spiders, many webs, and many centres. So, to answer your question, I’m with those who believe it’s preposterous to think that humans are in the centre of the planet and universe or that there is only one web and one way of entangling it.