The idea for the first edition of hube magazine came after a conversation between editor-in-chief Sasha Kovaleva and I during my art residency in Bremen, Germany. I had been invited by the artist and curator Effrosyni Kontogeorgou at the Güterbahnhof Areal für Kunst und Kultur, with the theme of ‘niche(s)’. The term niche describes the role an organism plays in an ecosystem.

The construction of biological niches is the process in which organisms adapt or change conditions for themselves and other organisms in their environment. The ecological term niche goes back to the architectural term, which means a recess in a wall for a statue. It probably comes from the French word nicher meaning ‘nest’. This polysemy of the term in English and German does not occur at all in Greek as a singular word. Just by translating it into Greek, several words, new images, and contexts could emerge. With that, I focused on the question: do niche constructions belong to the realm of ordering or are they anarchic collective structures of becoming, while displacements of cultural ideologies or heritages become a negotiation of power or colonialist interpretations?

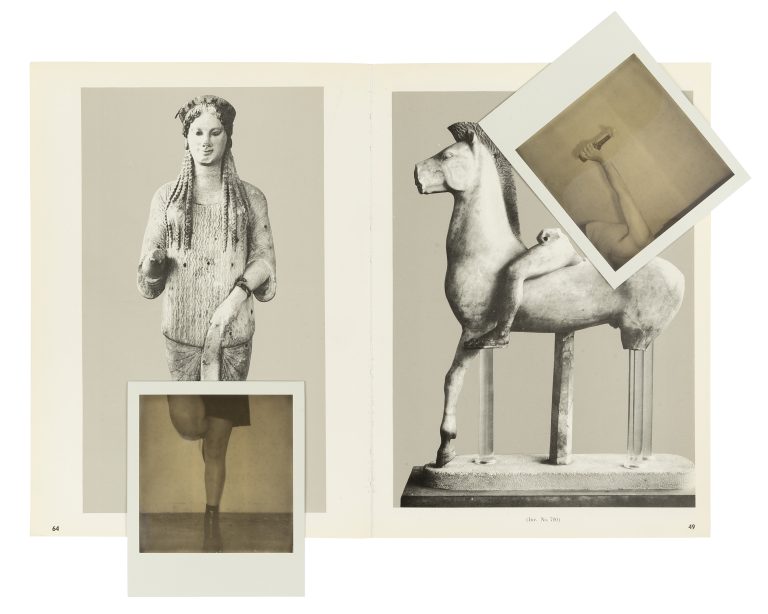

Carrying out this action in Berlin’s Altes Museum takes a humorous approach, like artistic practices in the early 20th century in Europe—in particular, art movements that tried to destroy traditional notions of good taste. Also, characteristic of this action is the choice of the medium of ephemeral collages through a performative, almost surreal process of uncovering how to use museum antiquities in different ways.

This interventionist project can be perceived as an attempt to subvert the monolithic discourse on the ancient Greek classical ideals about art, philosophy, and democracy by bringing to the fore imperialist and capitalist practices. As important and internationally widespread the concept of democracy is, so is the concept of anarchy. Etymologically, the word ‘anarchy’ comes from the verb άρχω—to lead, to govern, to rule, to dominate (with the prefix ‘a’) or from the noun αρχή related to hegemony, power, government, and leadership. ‘Anarchist’ is thus the same as the ancient anarchos—a(n)+archos—where archos meant the leader and is, therefore, one who does not want to be ruled over and wants to be autonomous. If in the Stoics we find anarchist theory, in the Cynics we find anarchist practices with the solemn and superstitious dissolution of every value and institution of organised society, with Diogenes of Sinope (412–-323 B.C.) being the most important representative of the Cynic movement.

Photography by TAREK MAWAD