Photography by STEVEN TAYLOR

Pseudonym, 2024

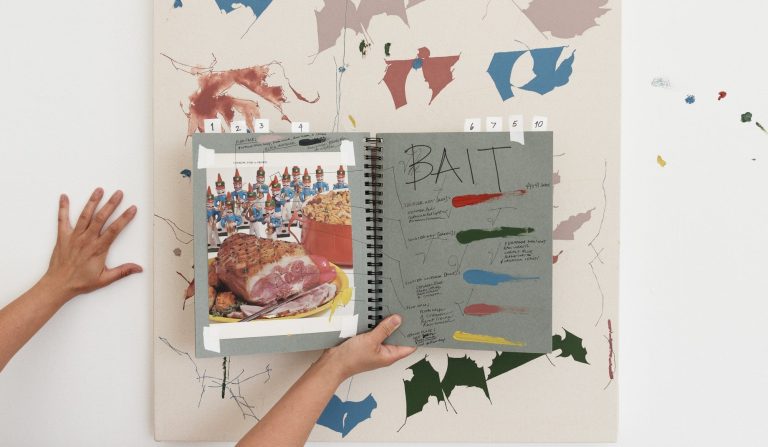

yesterday I was a tiny tube of toothpaste installation view, 2024

Photography by KEIZO KIOKU

In yesterday I was a tiny tube of toothpaste, Maysha Mohamedi reflects on her time spent in Japan two decades ago, revisiting personal diary entries to create a deeply introspective body of work. Her exhibition at Pace Gallery Tokyo features abstract paintings that blend emotions from her past with her current self. Through this process, Mohamedi explores themes of growth, connection, and the fluidity of time, offering viewers a glimpse into her journey of self-discovery through art.

hube: Your recent exhibition yesterday I was a tiny tube of toothpaste at Pace Gallery Tokyo features new works inspired by your personal diary from your time in Japan two decades ago. What encouraged you to revisit these diary entries and how were they transformed into visual art? Are there particular entries that stood out and significantly influenced the pieces?

Maysha Mohamedi: When I found out about the Tokyo show a year ago, I immediately thought back to my time living there in 2004. I was 24, in a PhD program for neuroscience, working in a lab, and all I wanted was to be an artist. I started reading my old diaries and re-entered that part of my life – being a young woman trying to figure out what I wanted and how to get there. At the time, everything felt so far away. I was surrounded by brilliant minds, and I badly wanted to have an impact like them.

Reading those diaries now was honestly shocking. I didn’t recognise that girl at first – she seemed so naive, even silly. But over time, I developed a lot of empathy for her. I realised that despite the time gap, we wanted the same things, and that really shaped the paintings. I started pulling out themes, concepts, and people from that period and translating them into visual forms for the exhibition.

h: The new Pace Tokyo gallery, designed by Sou Fujimoto, has a minimalist and ethereal design. How did the unique architectural features and atmosphere of the gallery space influence the presentation and arrangement of your works? Did the gallery’s design inspire any specific aspects of your exhibition?

MM: When I was creating the paintings, I wasn’t actively thinking about the architecture. But something interesting happened toward the end. About a month ago, I was looking at a rendering of the layout, with all my paintings placed where I imagined they would be. We realised one wall was missing a painting – it felt incomplete.

I had ordered a circular canvas, something I’d never worked with before, just to experiment. It was a small one, only 15 inches in diameter, but it hit me: this is the missing painting. It felt like a period at the end of a sentence, especially with its placement at the end of a line of paintings. That painting became the Full Stop. Later, I read an article about the gallery’s architect, who said curved edges were a key feature of the space. It was almost like the universe was telling me this circular painting belonged here.