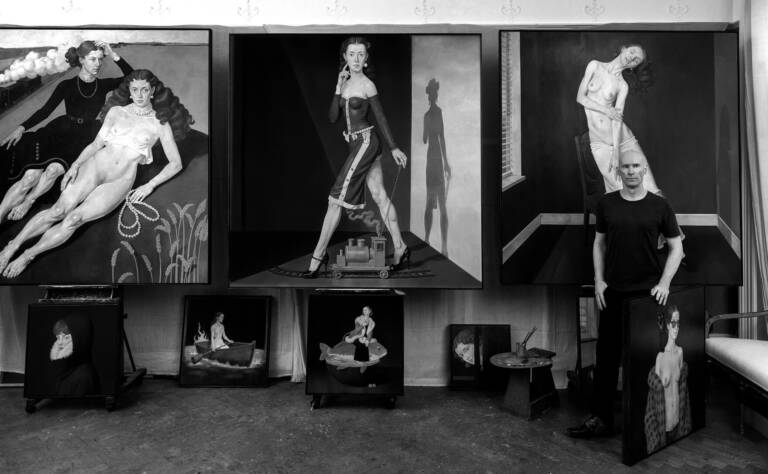

London based artist Von Wolfe works where oil meets algorithm. Trained in philosophy at NYU, he builds images like arguments, treating history as a living archive rather than a fixed reference. His portraits slow the churn of self-images and return the viewer to duration, presence, and the fragile depth of being human.

The process begins with computation. Wolfe trains custom LoRA models on his own archive until strange outliers appear, then edits and translates those forms to canvas, where touch gives them weight. Clothing reads as psychological architecture, site can become a collaborator, and music and literature set the tempo. The point is not to dissolve the tension between mediums, but to let them speak to each other in real time.

hube: You studied philosophy at NYU before fully entering the world of art. How has that philosophical foundation shaped the way you construct images?

Von Wolfe: Philosophy trains you to look at the structures behind what appears obvious — to question not just what something means, but how meaning itself is produced.

Thinkers like Wittgenstein or Derrida remind us that meaning is always shifting, never fixed, and my work mirrors this by placing historical, cultural, and technological images into constant dialogue. For me, art is less about providing answers than creating a space of questioning.

h: Your work carries the gravity of history yet resists nostalgia. How do you engage with the past as a living archive rather than a fixed reference?

VW: I regard history as a continuum rather than a distant past — a living archive where the same fundamental questions of human existence continually resurface. Themes such as love, grief, faith, or the struggle for freedom are not bound to one era; they recur in different guises across time. My work seeks to reactivate these motifs, translating them into forms that resonate with the present while retaining their timeless gravity. In this way, the past is not something to be nostalgically preserved but a vital source through which we can better understand both ourselves and the world we inhabit today.

h: Portraiture has long served to immortalize, idealize, or expose. What do you think its role is today?

VW: In an age overwhelmed by self-images, portraits risk becoming disposable, endlessly replicated, and consumed. Yet painting resists that ephemerality. A portrait slows time asking both artist and viewer to dwell in presence rather than immediacy; unlike the fleeting image on a screen, a portrait in oil insists on duration. Today, the role of portraiture is not simply to immortalize or flatter but to cut through the noise of simulation, reminding us of the depth and fragility of being human.

Photography by NICK KNIGHT