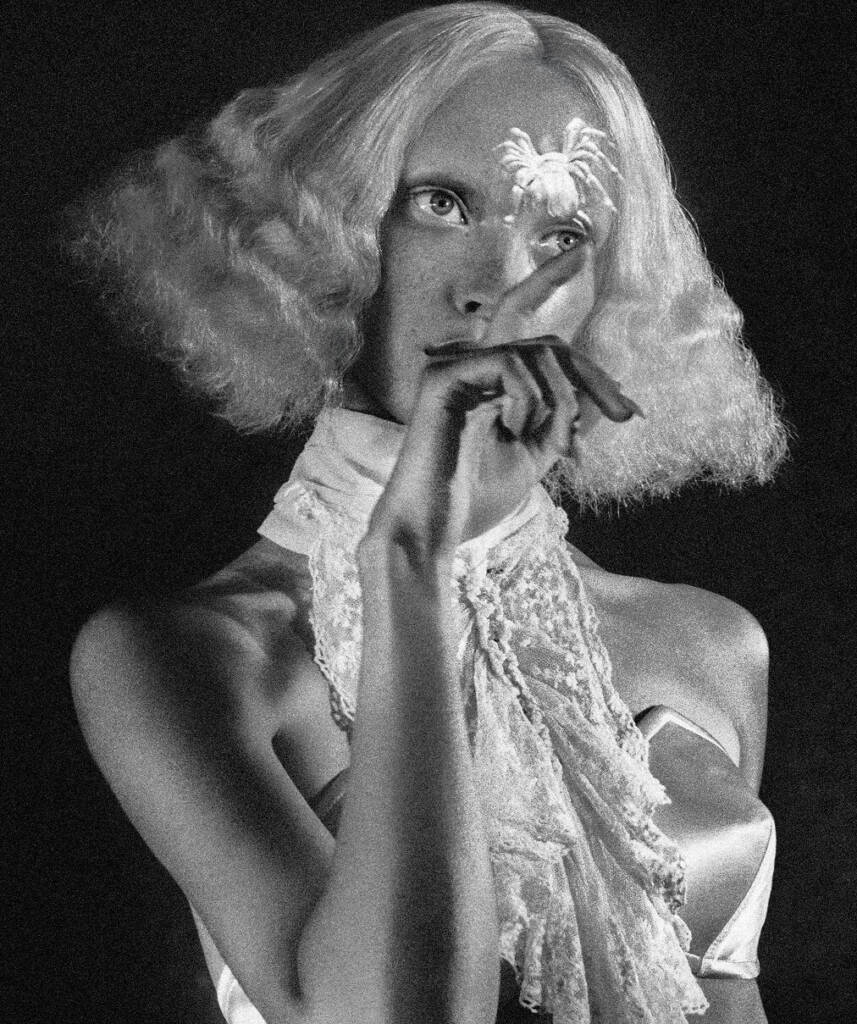

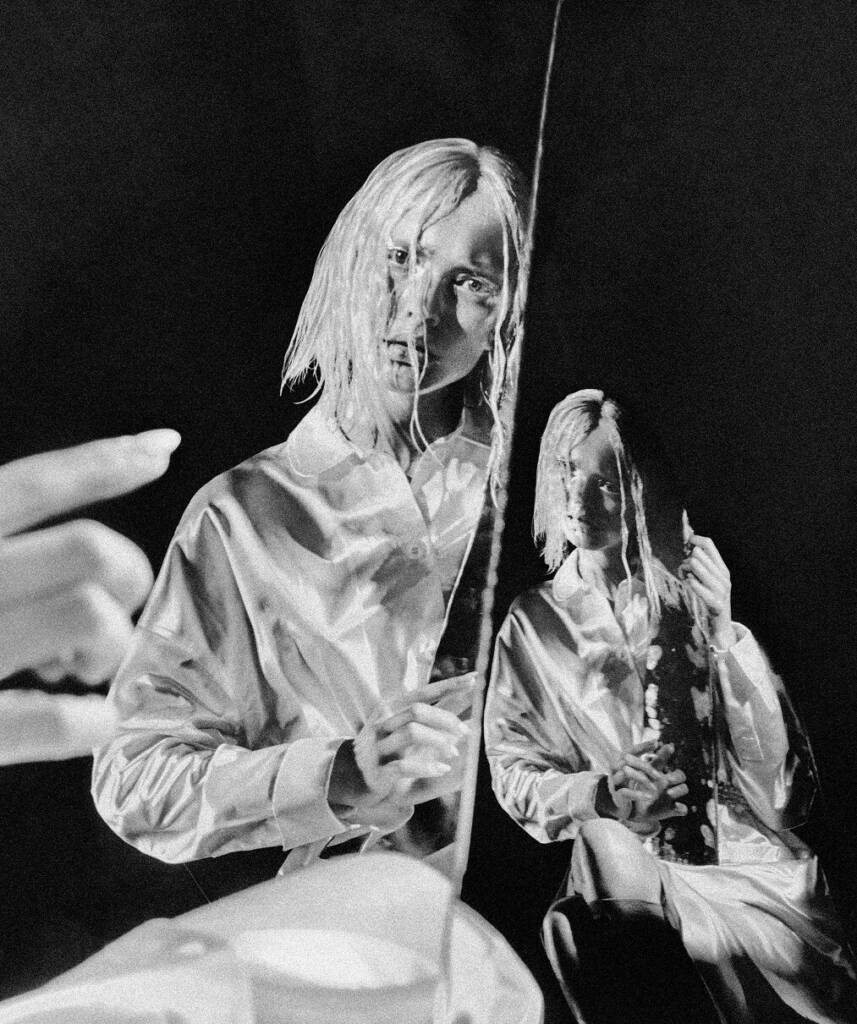

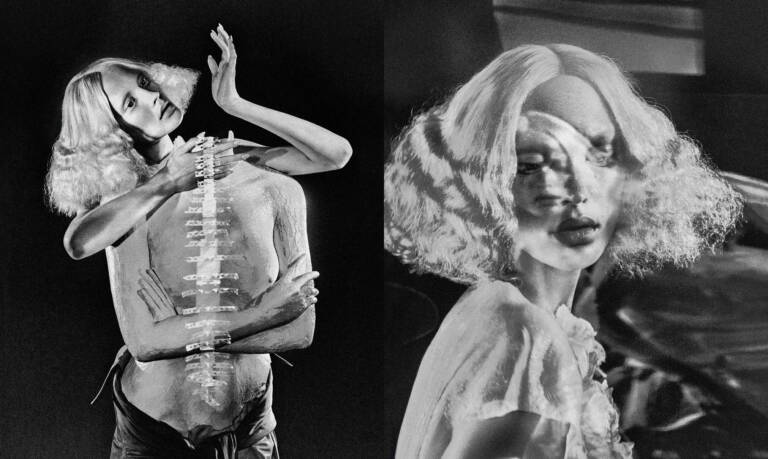

“What does it mean to be a good person?” asks Elizaveta Porodina. “How do kindness and dignity express themselves in human behaviour?” These questions guide her thinking and inform her practice, but her work doesn’t seek to answer them explicitly. Instead, it suggests a different kind of knowing: one that is cerebral, surreal, and sublime in its strangeness.

Porodina was born in Moscow and moved to Germany with her family as a teenager. Caught between languages, locations, and ways of being, she turned to art as a medium for understanding the world around her. She went on to study psychology, hoping to map the many territories of feeling, but found the practice offered distance rather than connection or expression. Photography returned her to something more essential, something that reminded her of where she belonged. “This is where my homeland is,” she says. “My native land is imagery.”

We spoke to Porodina about her work and the many things that exist beneath its surface: oneiric threads, the subconscious, and the life of an image before and after it reaches our screens.

hube: Culture creates stories and myths about good and evil, beauty and harmony. Your journey has led you through many different worlds. How do you perceive your cultural identity today?

Elizaveta Porodina: I think that the closest way I can answer this question is to talk about my personal journey. What kind of community, what kind of world, do I see myself in? I have always struggled with where to place myself, so I kind of see myself as a nomad: a traveller between worlds or an astronaut isolated from them.

Watching people in their various worlds connect and laugh and speak to each other, seeing them exchange verbal and nonverbal signals… for many different reasons, these interactions were sort of unattainable for me, and that made me feel isolated. I always felt like I didn’t fully belong to one culture or another.

When I was a child living in Russia, I found it hard to connect with key aspects of the lifestyle—it seemed quite intense to me. When I moved to Germany at 13, I found it challenging to adapt to another very different way of dealing with emotions. When I started studying psychology, I developed a strong cognitive understanding of people’s emotional behaviour, but I didn’t feel an emotional connection to it.

So, I think the first 23 years of my life were an odyssey, a journey to discover my own identity and to feel good and accepted. I found both acceptance and my way of expressing myself by going back to my roots. This is where my homeland is. My native land is imagery. This is what I understand. This is what I feel. And this is how I can express myself most authentically.

h: When we try to understand the world, questions often prove more important than answers. What questions are most essential to you right now?

EP: I agree with that. My questions are:

What does it mean to be a good person?

How do kindness and dignity express themselves in human behaviour?

What can a person do to have a positive influence on their immediate environment?

What is the essence and core of happiness and fulfilment?

Those are my biggest questions at the moment. This is what I’m asking myself pretty much every day.