By JJ CHARLESWORTH

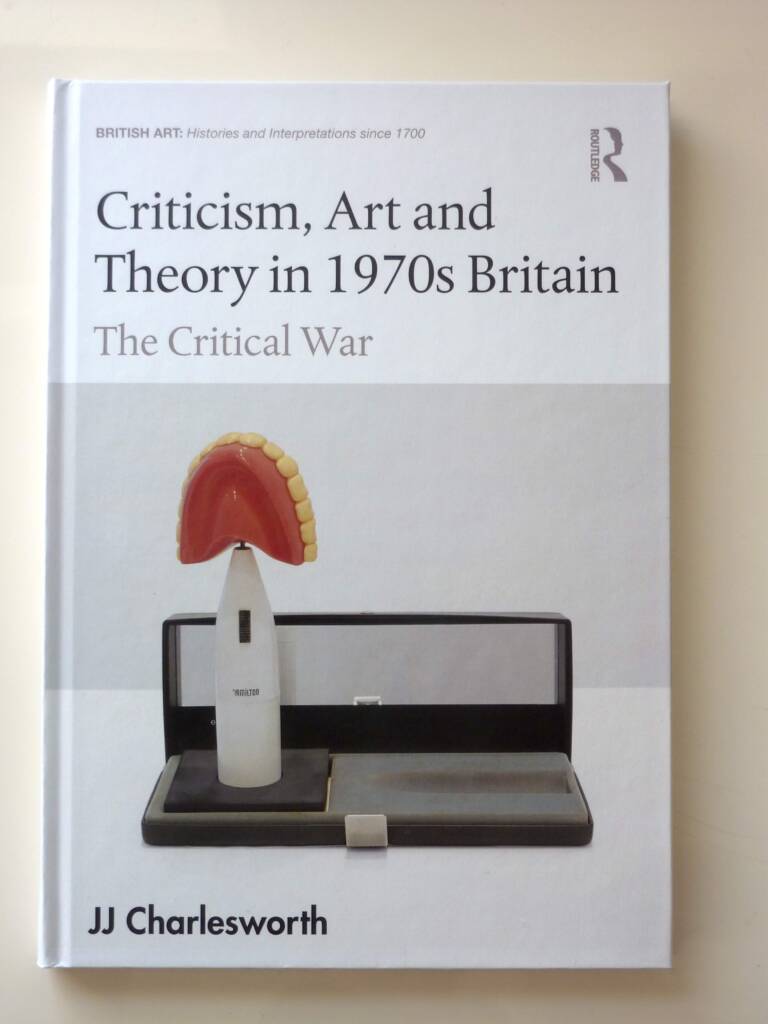

Published March 12, 2024 by ROUTLEDGE

Photography by SILKE BRIEL

ArtReview Asia Spring 2025

Art critic and published author JJ Charlesworth has been a sharp observer and tastemaker of the London art scene for over twenty-five years. In this conversation with hube editor-in-chief Sasha Kovaleva, he reflects on the state of contemporary art criticism, the evolving media landscape, and the intersections of art, technology, and culture.

In addition to lecturing at universities, he has worked as the editor of ArtReview, where he covers contemporary art from an inimitable vantage point—one that only experience and a versatility to connect—and challenge—a range of disciplines through time can create. In his recent book, Criticism, Art and Theory in 1970s Britain: The Critical War, Charlesworth turns the lens around, examining the role of the art critic rather than the artist, and the profession’s role in understanding the development and legacy of art as it is understood.

Sasha Kovaleva: In a time when cultural discourse is increasingly shaped by social media and rapid opinion cycles, what role do you believe long-form art criticism still plays? Can it coexist with—or even counter—the speed and brevity of online commentary?

JJ Charlesworth: I think there are two things going on right now. Social media is in a bit of a state of flux, and if the goal is just to drive readers to opinion pieces, then that’s not a bad thing. But the “opinion cycle” is a big problem because everyone is now forced to have a hot take immediately. There’s a lot of pressure on big media outlets to cover shows, exhibitions, and films as soon as they’re released. Long-form criticism, though, is for a dedicated audience and doesn’t need to compete with fast online writing. Long-form criticism (over 1,000 or 2,000 words) serves a different role, working through bigger ideas with more depth.

I see a lot of fast writing on art, but I’m not always interested in it because much of it is simplistic. Many new online art magazines have emerged over the last 10 years, but they don’t always last. This new wave of writing tends to be less regulated than older print culture, which has led to a more anarchic style that lacks the depth of traditional criticism. There’s always been fast, superficial writing on art, even in older print magazines. The question is whether there’s space for a more reflective, developed way of writing about art, tackling bigger theoretical or analytical debates.

Some platforms, like Substack, are experimenting with longer, more in-depth discussions. Platforms like e-flux have offered a consistent agenda, incorporating themes from politics, philosophy, and media theory. They’re a good example of a publication setting the terms for a type of criticism that has a definite influence on a particular kind contemporary art. But even short-form writing itself is under threat. Audiences may not be as engaged with the field as before, partly due to changes in how people relate to locality—where the publication is and where the readership is. Older art magazines had a physical and geographical relationship to what they covered. They addressed local scenes, and readers had some access to the art and artists they discussed. The internet has changed this relationship, dilating how we access and connect to art. Visual art is still primarily a physical experience, as galleries remain important. Unlike film or music, visual art requires a connection to physical venues. There are now many micro-scenes around small galleries, and social media—particularly Instagram—plays a huge role in bringing people together. But there’s less short-form writing covering this small-scale activity, which is I think a problem.

SK: In what ways do you believe art critics shape not only public perception but also the long-term historical narrative of art movements?

JJC: I think the idea of the art critic has become of a 20th-century anachronism, though this isn’t a great development, in my opinion. The role of the art critic has changed historically, partly due to shifts in culture and media. Many newspaper critics have been fired or retired, and the role of the individual art critic who writes for a broad audience has diminished. This is due to the rise of online media, online commerce, and the changing financial model of media. The figurehead critic with a significant platform is now less possible than in the age of monopoly media outlets.

But another important shift—perhaps the most significant—is the decline of the critic as the person with all the knowledge. Those who write criticism today are often more academic or more closely aligned with major theories and discourses, unlike the old-fashioned individual critic, who was usually more independent from the academy. In the last 20-30 years, critical ideas have moved from being part of independent, informal culture to existing somewhere between the institution of the art school and academia. Before the 1960s, radical ideas influencing artists came from politics, subcultures, and avant-garde thinking, with critics channeling these ideas. But there were usually outside—and often in opposition to—the institutions of art. After the 1970s, these ideas entered the academy and transformed it.

Today, critical discourse is shaped within art schools and universities, and curators and artists are more literate and engaged in theory, so, the critic no longer controls the discourse; they’re now just part of the conversation. The critic doesn’t lead the way as they did in the post-war, or even perhaps into the 1970s. In terms of long-term historical narratives of art, the art critic no longer plays a central role. Curators and art historians, who are part of academia, are now rewriting historical accounts. This is evident in events like Documenta and many other biennials, where curators themselves revise and direct art historical narratives.