She carved a star into her stomach. She lay naked on a cross of ice, bleeding under a heater. Decades later, she sat motionless for three months at MoMA, silently meeting the gaze of strangers. For most of us, pain is something to escape. For Marina Abramović, it’s a language—a way of communicating what words cannot hold. Over five decades, she’s turned endurance into a form of beauty and suffering into a form of care.

In a culture obsessed with speed, problem-solving, and dopamine, Abramović asks us to slow down. To linger. To stay. Her work is not about pain for its own sake, but about what pain reveals—the parts of us that recoil, the parts that endure, and the fragile space in between. She invites us into an encounter where art becomes a test of attention: can we truly look, without looking away?

Pain as portal

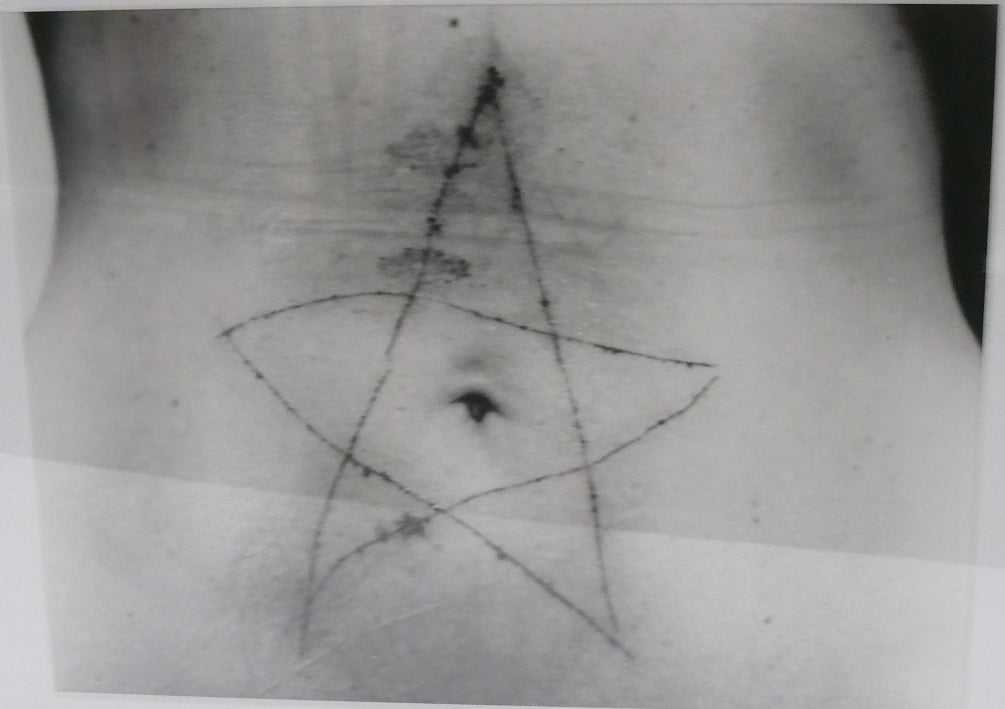

In 1975, at Galerie Krinzinger in Innsbruck, Abramović performed Lips of Thomas. She ate a kilo of honey. Drank a liter of red wine. Smashed a glass. Carved a five-pointed star into her stomach. Then she lay down on a cross of ice, bleeding beneath a heater, until the audience intervened. It was raw, messy, and strangely holy. In those hours, the body became both altar and battlefield, enduring its prayer. Watching her, the crowd wasn’t sure whether to flee or fall silent. A year earlier, in Rhythm 0, she stood beside a table of 72 objects: a rose, scissors, nails, honey, a knife, and a loaded gun. A sign invited the audience to use the objects on her however they wished. At first, they offered tenderness—flowers, kisses, laughter. Then came the unraveling. They cut her clothes. Drew blood. One man pressed the gun to her head. No one intervened until she finally moved at which point everyone scattered, unable to face her as a person again.

Looking back, Abramović said, “If you leave it up to the audience, they can kill you.” After six hours, as planned, she finally stood up and everyone ran. What unfolded in that room wasn’t just violence; it was revelation. The performance exposed how easily empathy can flip into cruelty, how the urge to connect can curdle into domination. The audience came to watch an artist, and left having met themselves.

Philosopher Simone Weil called such states affliction—a suffering so total it dismantles identity itself. Unlike ordinary pain, which we can describe or resist, affliction empties us out. It’s the collapse of control, the moment when the body and the mind stop pretending to be separate. For Weil, this was the site of the sacred: where the soul, stripped of comfort and ego, finally sees what it means to be human. Abramović takes that idea out of the realm of theology and puts it under the museum lights. She enacts what Weil imagined; the stripping of the self until only awareness remains. Pain becomes a shared experiment in ethics, testing the threshold of compassion: how long can we stay present before discomfort becomes too much? How long can care survive before it turns into voyeurism? Through this lens, her work isn’t about suffering at all—it’s about attention. The performance becomes a mirror, reflecting not her endurance, but ours.

Lips of Thomas (Star on Stomach), 1975, Framed black and white photograph with framed letter press text panel, Unframed, 49.5 x 59.7 cm|Unframed, 26 x 18.4 cm

Collection IRISH MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, Purchase, 1995

Rhythm 0. 1974

Courtesy of MARINA ABRAMOVIĆ and SEAN KELLY GALLERY

Rhythm 0. Performance 6 hours. STUDIO MORRA, Naples. 1974

Courtesy of the MARINA ABRAMOVIĆ ARCHIVES

Film still The Artist Is Present

Courtesy of SHOW OF FORCE

The Artist Is Present, 2010

Courtesy of MOMA

The quiet turn

Decades later, the mirror changed. The knives, the honey, the blood—all gone. What remained was silence. At MoMA’s The Artist Is Present (2010), Abramović sat still for three months for 736 hours, facing one visitor at a time across an empty table. No script, no movement, no violence, just gaze. Where her earlier works screamed, this one whispered. The pain was internal now, drawn out not by spectacle but by stillness. The tension moved from the edge of the blade to the edge of time. If Rhythm 0 showed us the danger of freedom, The Artist Is Present revealed the discipline of attention—a different kind of endurance, quieter but no less demanding.

Lady Gaga, Björk, and James Franco lined up like pilgrims. Cameras flashed, and suddenly stillness went viral. The work became a paradox: both deeply spiritual and completely Instagrammed. Yet even in the glare of spectacle, something real flickered. To sit across from Abramović was to feel time slow down. The silence thickened, the air seemed to hum. Many left in tears, unsure why. The piece proved that presence—raw, wordless, unspectacular—could still move people in an age built on distraction. Her art has always flirted with contradiction. It’s both performance and prayer, discipline and chaos, exhibition and confession. The quiet of The Artist Is Present wasn’t an escape from the violence of her earlier work, it was its transformation. Pain turned inward; endurance became stillness. But that stillness wasn’t spontaneous. It was trained, disciplined, almost ritualistic. To understand the force behind Abramović’s performances we have to look beyond the museum and into the practice that sustains it.

The Method

Behind the mythology of Abramović’s endurance lies something quieter: discipline. Her body isn’t just a site of art—it’s an instrument, tuned through repetition and deprivation. She fasts for days, practices stillness for hours, spends weeks in silence. Over the years, she’s trained with Tibetan monks, Brazilian shamans, martial artists, and mystics, borrowing from their rituals but shedding their religion. What remains is a kind of secular spirituality, built on focus and presence. For Abramović, art begins long before the performance. It’s in the empty stomach, the aching knees, the slow breath. She calls it a cleansing: stripping away ego until only awareness remains. When she performs, that awareness becomes contagious. The longer you watch, the slower your own pulse becomes. The noise of life—the mental tabs open in your head—starts to close one by one. It’s not something you just witness. It’s something you catch. The Abramović Method isn’t about faith; it’s about the encounter between artist and audience, self and other, silence and sound. In her world, attention is the only true form of devotion.

Healing without resolution

Western culture loves closure. We like to solve pain, archive it, and move on. Abramović refuses that storyline. Her art keeps the wound open long enough for meaning to appear, not as catharsis, but as connection. In The Artist Is Present, no one left the chair “healed.” There were no epiphanies, no clean endings. Yet something happened in that silence. People cried, not out of sadness, but out of recognition. When was the last time someone really looked at you—for minutes, for hours—without wanting anything in return?

That’s the subversive heart of her work. In a world monetized by attention, Abramović gives hers away freely. She turns the simple act of looking into a moral gesture. To meet another’s eyes and stay—without judgment, without agenda—becomes a quiet revolution. She’s often called a spiritual artist, but her version of spirituality is stripped of doctrine. It’s not about God. It’s about gaze. Healing, in her world, it’s the courage to stay broken together.

Photography by Hick Duarte

Courtesy of the MARINA ABRAMOVIĆ ARCHIVES

Courtesy of MARCO ANELLI/SERPENTINE GALLERY

Courtesy of GALLERIE DELL’ACCADEMIA in Venice, ‘by concession of the MINISTRY OF CULTURE’

Courtesy of GALLERIE DELL’ACCADEMIA in Venice, ‘by concession of the MINISTRY OF CULTURE’

Endurance as ethics

Endurance, for Abramović, is ethics, it’s a way of reclaiming depth in an economy that rewards distraction. To stay, to bear witness, to resist the reflex to scroll past discomfort, that’s where her art becomes political. In Lips of Thomas, the question was: how much pain can one body hold? In The Artist Is Present, it became: how much stillness can one room hold? Both demanded the same thing; presence as a form of resistance. Her audiences aren’t passive. They’re implicated. The longer they remain, the more responsible they become. To look is to choose: to care or to consume. To intervene or to turn away. Each second of watching becomes a moral act. Abramović turns museums, those sleek temples of spectatorship, into spaces of risk. She exposes how looking itself is structured by power: the institution, the camera, the celebrity. And still, she insists that attention can be an act of care. It’s not naive optimism; it’s radical insistence.

Presence beyond redemption

There’s no redemption in Abramović’s work. No salvation narrative, no happy ending. What she offers instead is something more fragile: presence. In her performances, pain doesn’t dissolve; it lingers, reshaped by attention. The body becomes the threshold between self and other, a place where perception is both wound and bridge. “The hardest thing,” Abramović once said, “is to do something that’s close to nothing.” Maybe that’s her greatest lesson. To endure without spectacle. To be still without disappearing. To see and be seen, knowing it will hurt a little. Her art teaches us that attention itself can be a kind of grace. That looking, truly looking, might be one of the last sacred acts left. In a world addicted to distraction, she reminds us: staying is radical.

Abramović will return to Venice in 2026 with Transforming Energy, a historic solo exhibition at the Gallerie dell’Accademia, which will be the first ever dedicated to a living woman artist in the museum’s 250-year history. The show will revisit works like Rhythm 0 alongside new pieces carved from quartz and amethyst. It arrives at a moment hungry for depth. Abramović’s work keeps asking the same difficult question: can we stay? Venice will only amplify that challenge. And in a city built on water and illusion, her work might finally show us what it means to stand still.

Words: ZSANETT RITLI

Zsanett Ritli is a Fulbright Scholar, a postgraduate student at NYU, and an alumna of the University of St Andrews. With a background spanning art, business, and philosophy, she writes through those lenses to understand how people see and make meaning.