After directing the feature film Demolition Man, artist and filmmaker Marco Brambilla developed a body of work exploring media and collective imagery through large-scale video installations—often using contemporary technology to evoke nostalgic visions of retrofuturism and to experiment with ai-assisted art. His Megaplex series—among others—has been exhibited internationally in museums, and his work is held in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.

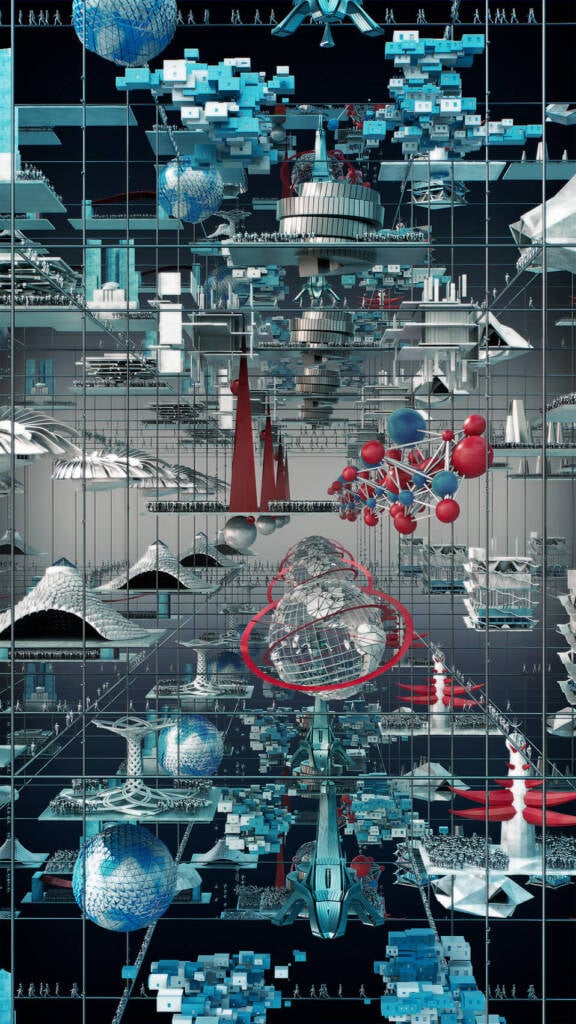

In 2024, Brambilla debuted the digital moving-image series Approximating Utopia across 95 billboards in Times Square, New York. His upcoming exhibition After Utopia, opening on the 2nd of December 2025 at The Wolfsonian–Florida International University in Miami and running until the first of March 2026, continues this conversation using artificial intelligence-assisted research and computer-generated imagery to construct virtual landscapes inspired by world’s fairs spanning three centuries. Animated from archival imagery of iconic structures, the work is presented in tandem with the museum’s exhibition World’s Fairs: Visions of Tomorrow, connecting past suppositions of progress to contemporary forms of technological spectacle.

hube: The exhibition is titled After Utopia. What drew you to this title, and what conceptual or emotional terrain does it open up within the broader arc of your practice?

Marco Brambilla: After Utopia is a title I came up with because we had the idea of using AI to create, or at least inform, a work that would also comment on the way AI is becoming a part of our world. Back in the sixties and seventies, there were all these architects who inspired me when I was younger—Archigram and Superstudio from Italy. Their work was always driven by a concern for a better life for people, a utopian condition, which was usually conceived physically. All their designs were meant to be realized in the physical world.

This led me to think about World Expos, and the idea that they have always embodied hope for mankind through technology. I’ve always been fascinated by World Expos. I visited maybe six or seven sites after they were decommissioned—Saka, Shanghai, Seville, Montreal, and Brussels. I’ve always been captivated by these arcs of civilization. They were like time capsules, preserving the spirit of their era. Every Expo introduced some new technology: in New York, 1964, a 360-degree movie theater for Kodak; in Osaka, a film screen that projected images on water mist; in Montreal, the monorail; in Dubai, 2020, the focus was on sustainability. Each Expo demonstrated the idea that technology—whether in engineering, electronics, or biotechnology—could improve human life and promote harmony with the environment.

If you were to imagine a utopia today, it would likely exist virtually rather than physically. A few years ago, there was a lot of discussion about the metaverse and digital environments where like-minded people could meet in infinite, reconfigurable spaces. I began this project when the first AI image generator was introduced and realized I could combine a technology that has the potential to both limit and expand our imagination. AI can enhance our ability to dream, enabling us to conceive ideas larger and more fantastical than what an individual could imagine alone. At the same time, it introduces an element of unpredictability—a shift in directions we may not fully control.

This dichotomy between technology and the spirit of utopia—the vision of cities that allow us to live in harmony with technology—is what truly fascinated me. I decided to create the work and selected 18 Expos to focus on. We trained the AI with extensive imagery and a wide range of data: national anthems, Expo statistics, attendance figures, and more. Then AI helped determine which pavilion to feature—the one that was most searched for or most celebrated in each case.

h: Could you walk us through your research process—particularly how you collected, analyzed, and reimagined historical material from the original pavilions while developing these moving-image works? What questions or themes guided your inquiry?

MB: I began working with the Wolfsonian Museum, where the piece will be shown for the first time, about two years ago. They hold the largest archives of physical blueprints, brochures, floor plans, and sculptures of pavilions up until 1970—everything pre-internet that was otherwise difficult to find for training AI models. My team and I visited the museum and were able to scan 3D models, images, blueprints, and various artworks, and then input the corresponding metrics. This became the foundation of the library.

For the more recent Expos, most of the research was done online, so the library was supplemented with digital archives. From this comprehensive collection, I began selecting the elements I wanted to feature and bring to the foreground. I was inspired by the idea of migration—people moving from one future to another—because each Expo had a specific chronology and geography. The lines of people you see in the final work are algorithmically generated: they correspond to the actual number of visitors to each pavilion that year, yet they also move across the conceptual grid that structures the piece.

AI was used from the very beginning for sketching and experimentation. I was particularly drawn to the idea of dynamic architecture, reminiscent of Archigram. One concept I especially loved growing up was the Plug-In City—a city that could move to the suburbs or countryside, bringing culture with it: movie theaters, book readings, circuses—a fully mobile cultural hub. AI allowed us to animate the buildings according to the movement of people, creating unexpected and surreal simulations that made each Expo come alive.

The research phase involved extensive training and input—perhaps too much at times—followed by a careful selection of the information most relevant to the final vision of a future utopia. That vision is what After Utopia represents: distilling all these time capsules into one hopeful future, just beyond reach, just over the time horizon. That was the core idea behind the work.

Photography by KOEN BROOS

After-Utopia

Courtesy of MARCO BRAMBILLA

After-Utopia

Courtesy of MARCO BRAMBILLA