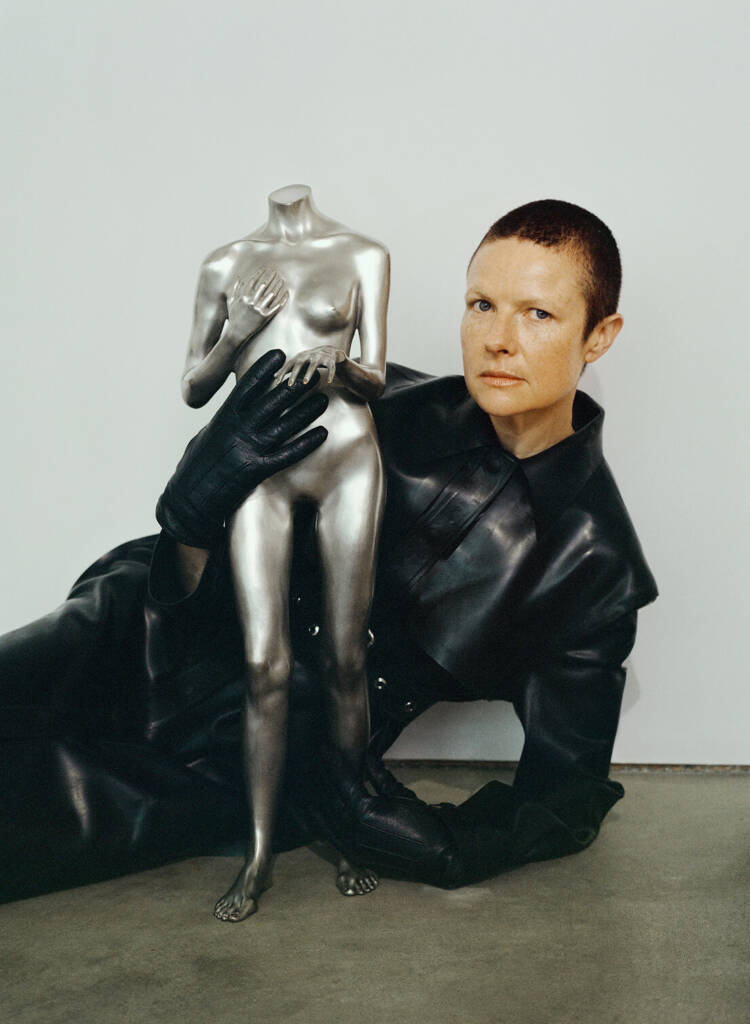

Wearing KWAIDAN EDITIONS

Photography by OLIVIA MALONE

HEAD WITH TONGUE, 2024

Photography by LEE TYLER THOMPSON, courtesy of the ISABELLE ALBUQUERQUE and NICODIM

Isabelle Albuquerque’s great-grandmother was a traditional Malouf singer in North Africa. Her grandmother, a playwright; her mother, a land artist; her sister, a dancer. Spanning continents and disciplines, this matriarchal lineage has created fertile ground for a new kind of creation. Albuquerque’s art is just this.

Trained in architecture and theatre, and with a background performing and playing music as part of Hecuba, Albuquerque came to sculpture in 2016. It began as a compulsion, a response to the first election of Trump. Working with plaster and clay, she made heads and phallic forms that she would later destroy. Though this new phase of work was born from a place of fear and loss, for Albuquerque, it has grown to reflect power and possibility.

The artist is best known for the life-size figurative sculptures that she models from casts and 3D scans of her own body. Inspired by ritual and mythology, she reshapes symbols and stories into contemporary provocations that confront traditional ideas of desire and control. Albuquerque releases the body from the male gaze, reclaiming it as a site of embodied power.

Amidst a busy year of exhibitions, we spoke to Albuquerque about her practice, the fluidity of gender and desire beyond fixed identities, and the necessity of hope as humanity careens toward an increasingly uncertain future.

hube: Human consciousness, and the creativity it gives rise to, remains one of the great scientific mysteries. How do you understand your own creative energy?

Isabelle Albuquerque: My muse is a kind of dom. She wakes meup at four in the morning. She makes me dowhatever she wants. She tortures me. Shedelights me. She makes me lose control. Iam at her mercy.

Sometimes, I don’t feel I have enough bodies to fulfill all of her demands. And aspects of my series Orgy For Ten People In One Body are about that: the desire for multiple lifes-

pans to do all the making. All the loving. All the dying. All the destroying. All the reaching and soaring and falling that just one body can barely begin to wrap its arms around.

h: The body—living and vulnerable, mythological and otherworldly—is central to your work. In art, is the body a tool, an object, or a subject?

IA: My body is the thing that connects me to all other bodies, to humanity, and to a kind of shared experience. A very human experience that is outside of, for example, the experience of an algorithm or an artificial intelligence that doesn’t understand pain, bleeding, pleasure, being hurt the way that someone who has a body might. Through this corporeal understanding comes empathy. In this way, the body for me is an instrument of empathy.

h: You engage with femininity, sexuality, and identity. Are there personal taboos when it comes to your work, or do you see artistic expression as a domain of unrestricted freedom?

IA: I see it as a place of freedom, with all the burdens that freedom carries.