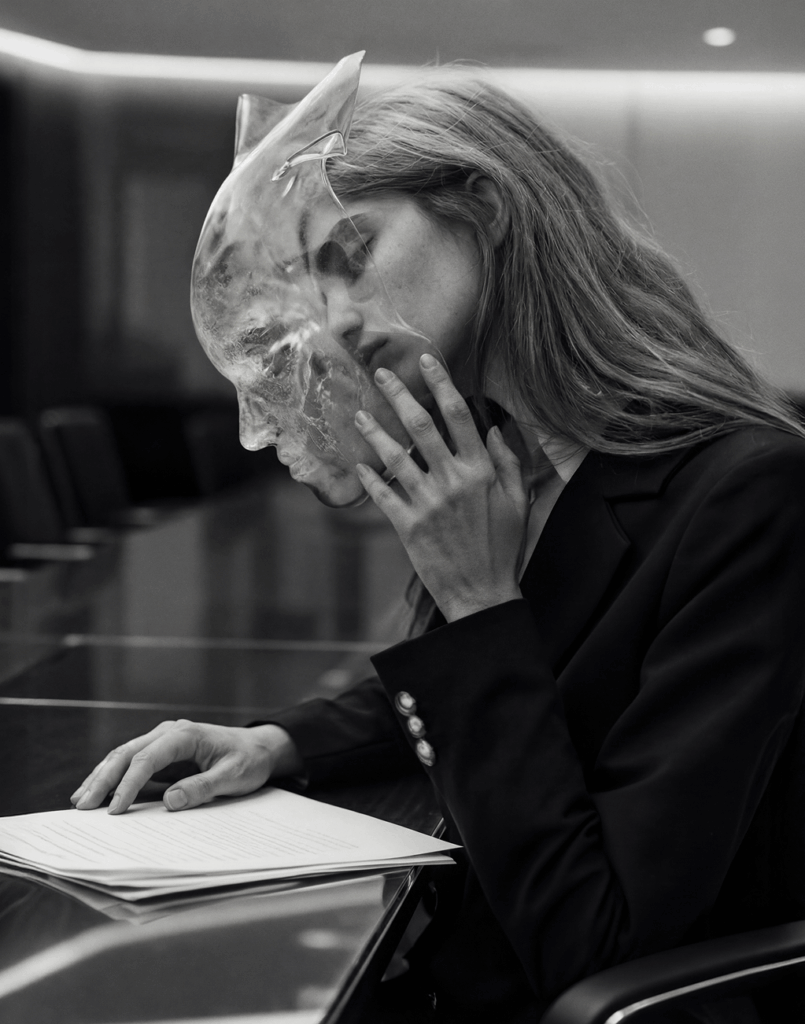

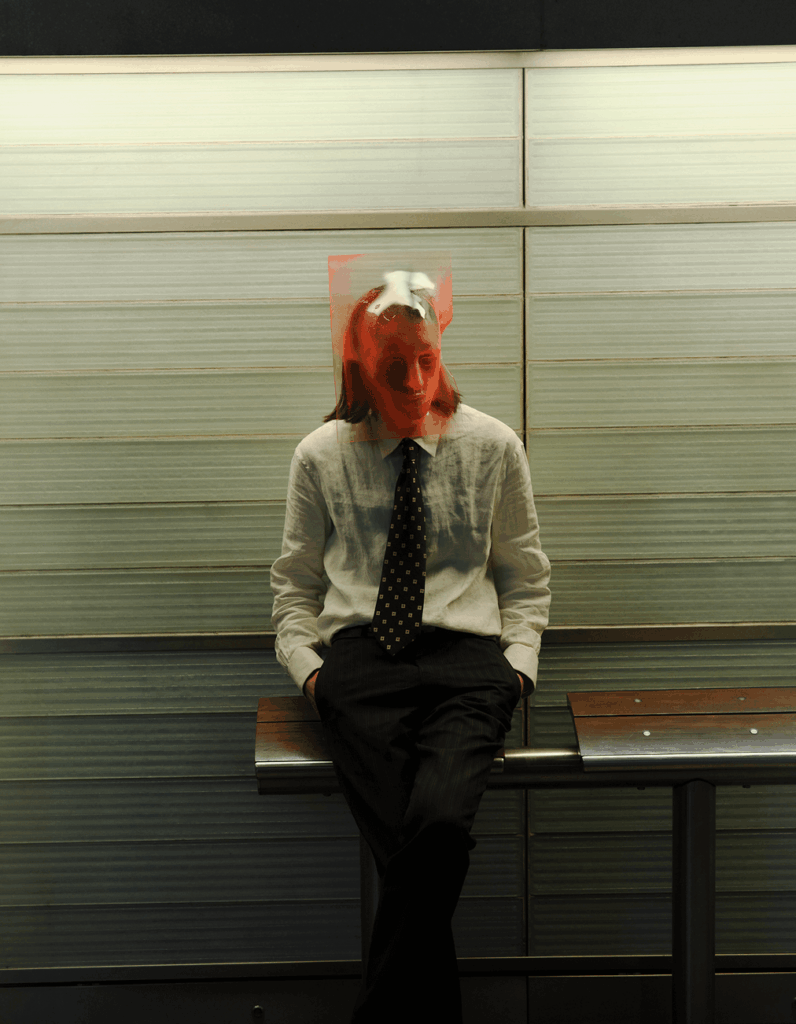

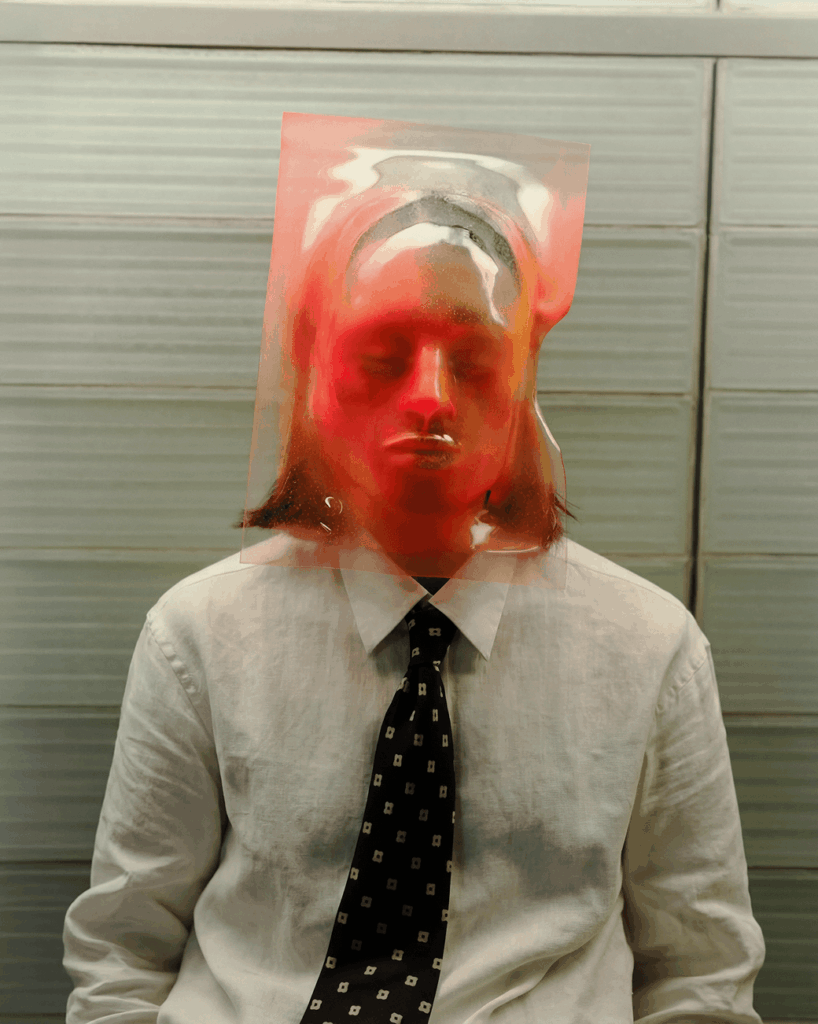

Face Value is a photographic series by Rowan Papier, featuring sculptural works by Amin Bidar, photographed across Paris as a special commission for hube magazine.

Moving through public spaces—cafés, metros, art schools, offices— Bidar’s masks, busts, and sculptural forms are unexpectedly embedded into the city’s everyday rhythm. Seated on bodies and placed within real environments, the works act as physical extensions of the inner world: projections of thought, emotion, memory, and inherited pressure.

Alongside the images, Rowan Papier engages in a conversation with Amin Bidar, reflecting on his creative practice—its origins, emotional undercurrents, and evolving language.

The series explores the tension between outward composure and internal complexity, staging a quiet confrontation between what is seen and what is concealed. Face Value makes visible the mental and emotional states we are conditioned to hide, offering a portrait of emotional interiority set against the expectations of societal restraint.

Rowan Papier: You work in three dimensions with stone, polymers, light, and projection—materials that each carry their own language. When you’re creating, how do you sense that a piece has reached its true completion, that moment when it can finally stand on its own?

Amin Bidar: I feel a piece is finished when it becomes very hard for me to work on another one whereas I didn’t show the first one to the public. I think the more you create, the more your gesture seems defined and the less the objects around you are defined.

RP: Your vertical forms seem to ascend—as if drawn by an unseen force rather than built from the ground up. What inner or symbolic impulse drives that upward gesture?

AB: I am glad that you feel the form ascending, because this is my intention. Using a certain “texture code” with transparency, sprayed paint dyed in the mass zones, or super-smooth elements, I try to give spectators the opportunity to think in terms of a celestial register—or, we could say, a metaphysical or spiritual register.

Beyond textures, I use forms, environments, their relationships, and colours, etc., to manage contrasts in the object so that it appears in tension, as my mentor David Altmejd explained to me.

I love to use very pragmatic techniques to create an ascending movement, which I call “verticalisme.” It means creating an object that is taller than it is wide, placed in a space that is also taller than it is wide, and captured in portrait orientation to evoke a vertical sensation in the spectator’s mind. It’s classic Gothic, in a way.

But you know what? I create almost everything on the floor, away from the desk, on my knees, as if I were charging the object with energy and, at the same time, unifying it with myself, being very close to it. Like Mary was close to Jesus in the Pietà, as if the same being were both dead and alive at the same time.

The creator who knows how to regard his creation unifies himself and the object into a single body, as if this body, by observing and forgetting itself—like two complementary poles—generates energy.

RP: You’ve said that you seek to manifest unknown entities rather than represent what already exists. How does that philosophy guide your choice of material and the eventual form a work takes?

AB: It guides my choices by making me able to take physical risks, intellectual transversality, poetic contemplation, spiritual emptiness, mystic identity, to manage the room for the unknown or the unmanifested to come.

RP: Titles like SELF SHORTCUT, SHIP SHIFT, and HALO I feel like fragments of an inner language—cryptic yet resonant. How do your titles emerge, and what kind of dialogue do they create between word and form?

AB: They emerge from my philosophical education. I mean, from the deep belief that Reality is explainable to itself—unified, subtle. Philosophy and mathematics are existentially warm. They are not complicated in themselves, because their fundamental goal is to explain, to connect things.

Relative to this aim, we can consider that they are never complicated, or should never be complicated by definition. That’s why, when I feel they are complicated, I tell myself: maybe you are tired, or sad, or impatient, or perhaps these are just less exciting compared to the ones you have already discovered—but this does not mean that reality itself is like you.

Take your time to create your own “language.” When I was younger, I felt intuitively that “discourse” is destructive. Discourse may seem useful in the short term, but it is destructive in the medium and long term, because discourse is a translation of energy, whereas language is an actualisation. Language is alive.

RP: You studied law, practiced judo and rugby, and then turned to art—three worlds built on structure, motion, and discipline. How do these earlier experiences continue to echo through your process and sensibility today?

AB: Most of the time, like many people, I try to live according to a balance, according to a dynamic created by triangulation. It makes me actualize; it makes me feel alive.

Structure, motion, and discipline are complementary, creating a system where each element is irreplaceable within the system but insufficient alone outside of the trinity. Structure brings stability, motion brings instability, and discipline never stops trying to link the two, at every moment, everywhere.

It’s all about balance—not as a concept so precise that it seems close to death, but, on the contrary, something so precise that it is open and alive. This is paradoxical. I truly believe there is more room in the middle of a mathematical line segment than at either of its two extreme ends.

RP: Living and working in Paris means being surrounded by both history and constant flux. How does the city’s rhythm—its density, energy, and contradictions—shape your creative pulse?

AB: Paris is my NYC, my Beijing, my Roma. Objectively, it is a human front for exploration, creation, and meditation; subjectively, it is a light I have loved, I love, and will continue to love.

It both protects me, offers me possibilities, inspires me, and puts me in contact with hard realities. Paris is an enhancer—an “exhausteur” in French, which is close to “exhausting” in English. Like Parisians, we all try to build a Paris that enhances life without being too exhausting to live in.

RP: I often think of light and shadow in portraiture as ways of revealing interior states. In your practice, beyond its material or optical role, what emotional or spiritual dimension does light hold?

AB: Light is interesting to experience, both as a creature and as a creator. I think there are too many types of light, but we could simplify them into two categories: one physical and one metaphysical — or, on a less visible frequency, we could say.

Global light links the material and immaterial worlds, more precisely the manifested and the unmanifested worlds, as René Guénon might say. Physical, visible light defines objects, permeating our relationships between beings as humble creatures thinking we are creators, and in doing so—by the same act—undefined subjects, making us believe that light is external to us, whereas the real light is within us.

Physical light could be considered as a mixture of the inner light of all living beings, creating objectification, whereas everything is part of the same unique being: Reality.

RP: You describe meditation as a principal state of being. When you’re in the studio, what shifts when making itself becomes meditation—when awareness and creation merge?

AB: I think everyone is always in a kind of meditation because, as living beings, we are linked to the Subject, the Totality, Unity, or Nature, as Spinoza would have said.

But the studio is a ship that allows me to move closer to the Source of the Subject. It is a constructed place, just as my ideas are constructed spaces meant to become spaceships. So you’re right—it’s interesting to keep this idea of shifting.

In the studio, I shift into an active meditation when the space is built well enough to allow me to remain meditative, connected to an indescribable Reality, while keeping my eyes open and continuing to act in the material world at the same time.

The goal is to gently reach a deep concentration in order to act across different levels of Life. If I superimpose several dimensions or frequencies too quickly, I may see degenerate forms; but if I do it slowly and subtly, I will see true forms—or even the Truth itself.

RP: Beauty has many faces—it can attract, unsettle, or transcend. Within your work, what kind of beauty are you searching for, and what purpose does it serve?

AB: I search for Socratic beauty—not a superficial, material one, but the kind that is synonymous with Truth. Again, it’s about an energetic trinitarian system. The concepts of Beauty and Justice are parts of Truth, yet they are able to express it complementarily.

If we listen to Einstein, Time exists only relatively for the one who is attracted by someone more powerful than themselves, just in the moment when the attracted is joining the attracting. So Beauty becomes a very interesting way to empower us when it is combined with Justice and Truth, because they are the source of attraction.

But if they are used incorrectly, they will not be effective. You will not be attractive, but merely attracted. Perhaps beings must pass through the two turbulent zones of pseudo-beauty in order to access the deep Beauty of the living axis of Truth—the Self, according to Ramana Maharshi.

RP: When I photograph the human figure, I see it as both subject and mirror. In your sculpture, does a trace of the human form remain as an echo, or is your aim to dissolve it entirely into something beyond recognition?

AB: I think both, questioning the solidity of human form as a scientific hypothesis. I remain and dissolve to express a vibration, trying to help the spectator to accept, to understand, maybe to feel what a more achieved being could look like.

RP: You often highlight your creative community and fellow artists in France. What role does that circle play in your practice—dialogue, challenge, belonging—or is solitude still your truest space of creation?

AB: I hope to highlight them enough, but I am not sure I do it enough, you know. Feeling alone deserves effort. Certain persons are a little more gifted than others, but it is always a science to feel alone, I mean by being alone concentrated.

It is a science to have real fellowship as well. Contrast is exhausting to live for beings, and it’s hard to believe that Grace is still active at any moment, available for each person challenging itself into sincere focus.

There exists material finished energies and infinite energy too. Let’s have confidence in that. I don’t think it’s deism saying that.

RP: Among your works, is there one that feels particularly honest or revealing—a piece that still mirrors a moment of transformation in your life?

AB: I remember a small face I made in 2019, published on my Instagram as Time in February 2020, after I took a few shots of it on the wall of No Gallery in Los Angeles. To me, it feels incredibly alive. Doing art while traveling is always special.

The piece is a kind of sundial, exposed outside the gallery in public space, on the south side, full of light—the most important part of the year. The spectator, facing the piece, is forced to cover it with their own shadow, but there is a small beam of light in the transparent face between the nose and mouth, creating a kind of backlight, reminiscent of the Hindu notion of Neti Neti, like Narcissus finally reaching near God.

Now, I want to speak about a second piece, the most important to me, the most refined I have shown: Timing Hit I, at Pact Gallery in Paris. The director, Pierre Arnaud Doucède, saw the piece at Poush, a well-known French collective studio. He met me and then presented the piece a few weeks later in a group show with Amy Brener, Igor Hosnedl, Emily Ludwig Schaffer, and Isaac Lithgoe.

The piece was published on my Instagram on June 1st, 2022. It embodies all that I have worked on, from my beginnings alone in basements to an important Parisian gallery. I will always be grateful to Mr. Doucède and Mrs. Trivini for seeing something in my work without any recommendation—just pure artistic intuition.

More technically, I think this piece is important because it expresses two fundamental ideas of my intellectual artistic search. First, when aligned to itself, individuality improves its ability to embody totality. The rosary symbolism is linked to a symbolic “shortcut painting” technique.

The second idea is that the creator’s gesture heals the body so completely that it can be considered as being the body itself. The plexiglass forms in my pieces are gestures, capable of managing their own destiny, serving as the keystone of Reality. They appear suspended in emptiness, depending on an external force, yet they are the foundation of everything.

RP: I often think of portraits as conversations rather than poses. When your sculptures coexist in a room, do they speak to one another—or does each insist on its own silence and presence?

AB: Your questions have been very interesting, Rowan, and I am very grateful for that. Thank you.

I like the vibration between the two ways of demonstration, when there is just one sculpture in the space or two. In the two cases, the architectural dimension is super present and the relational dimension too.

One suspended sculpture expresses maybe more the architectural dimension of the object, and the second expresses more the relational dimension between objects according to their positions with one another, but also as a group in relationship with the spectator. I like the suspension because the spectator has to turn around, as if the sculpture were on a pedestal, but he can go underneath as well, so his point of view is rich.

RP: There’s a quiet power in your vertical structures—they feel like witnesses or sentinels. In your eyes, what are they standing guard over, or what kind of silence do they hold?

AB: You evoke silence, which is so important to me. Simpler than meditation, the concept can still create apprehension. It is a shared silence that I would like to encourage with these suspended sculptures.

As in Nicolas Bourriaud’s exploration in Relational Aesthetics, the sculptures are socius — a relational face with Emmanuel Lévinas, an eurythmy with Rudolf Steiner, even if this last reference is controversial.

RP: As digital and AI technologies increasingly intersect with the arts, what possibilities or tensions do you see emerging? And do you imagine integrating any of these tools into your own exploration of form and presence?

AB: In my Muslim culture, the concept of witness is very important. The creative act, as in Henri Bergson or Muhammad Iqbal, is a testimony—an actualisation of the living link between beings as parts of the same Body.

The sculptures try to encourage you to be sentinels with them, sharing the responsibility to create — a responsibility inseparable from the secret of Acted Hope: dignification, a sincere act to improve something, to strive to elevate it, to make it more noble.

Presence in the process is key. AI tools are useful for researching information, but not for creating it. AI cannot successfully combine, for example, a painting by Leonid Ouspensky with a sculpture by Anish Kapoor or Antony Gormley. Artists like Diego Perrone or Josep Subirach succeed in expressing presence, sometimes with a liturgical dimension in their objects, as in the work of David Altmejd.

Louise Bourgeois, Pierre Huyghe, Marguerite Humeau, Jean-Marie Appriou, and Vermeer are inspirations for me. They are aware of a kind of ambidexterity in gesture, a sense of depth. I always try to feel my own gesture as balanced, like ambidexterity, to welcome the grace of presence—as if, by being focused, we could create more space within the same physical bounds.

Photographer: ROWAN PAPIER

Sculptures & Masks: AMIN BIDAR

Art Direction & Set Design: STUDIO FAVREAU

Models: ROSE DUSSER and TAIYO

Production: JAMESON PEPPER and DEARSYLVIA