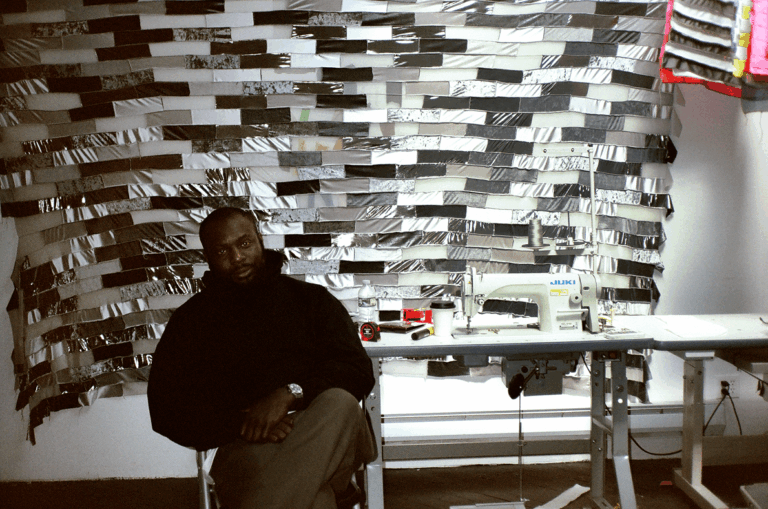

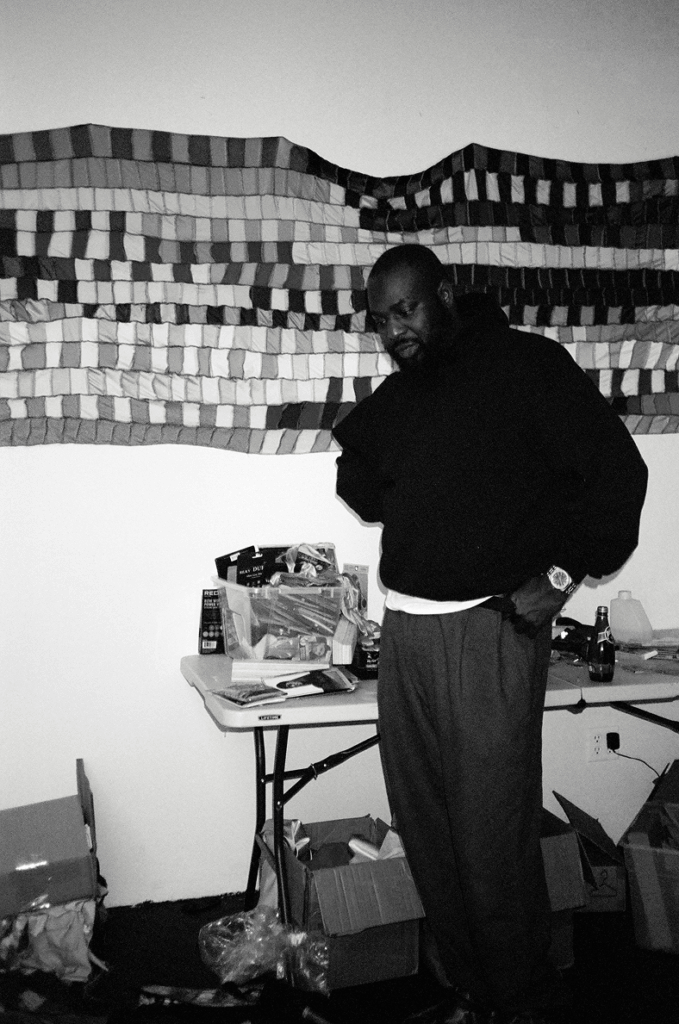

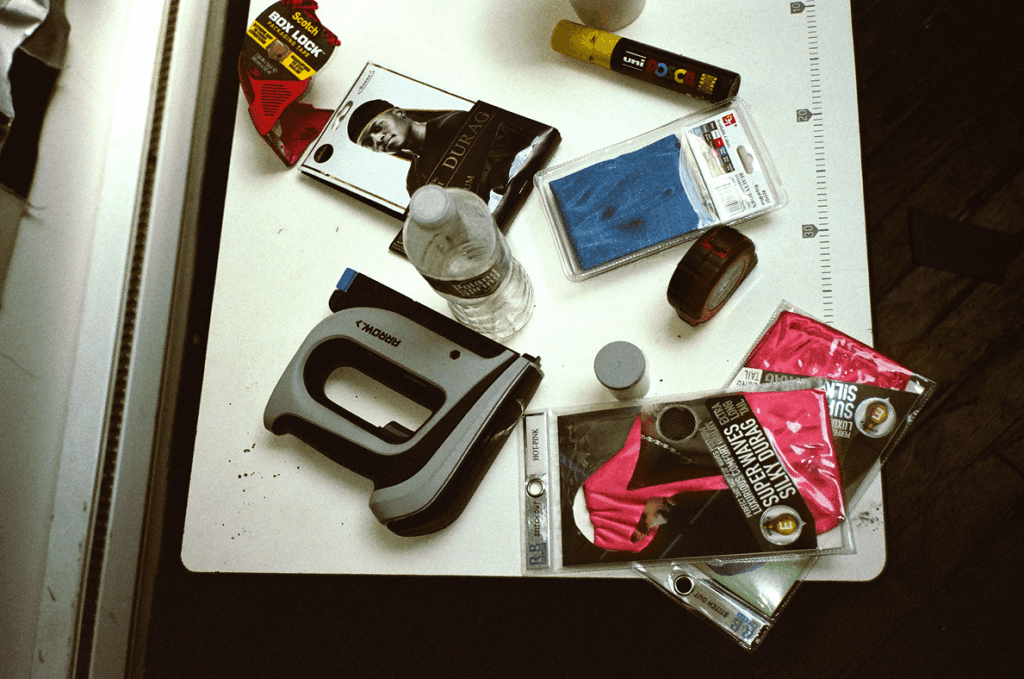

Nigerian‑American artist Anthony Olubunmi Akinbola has emerged as an incisive voice in examining the diasporic Black experience within the material world, making profound contributions to contemporary conversations on identity in art. His celebrated Camouflage works repurpose, with reverence, the durag as a medium—large textile‑based pieces that carry with them the ever‑evolving story of the African American experience. Akinbola has exhibited at leading institutions, including the Institute of Contemporary Art San Francisco, Schirn Kunsthalle, and the Museum of Arts and Design in New York City, where he currently resides, and his work is featured in major international collections such as the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, the Pizzuti Collection, the Speed Art Museum, and the Ogunquit Museum of American Art.

At only thirty‑four, Akinbola has already made his mark on the New York art scene through his ability to position contemporary cultural criticism within a larger global context, demonstrating mastery over his craft while suggesting that his most defining work may still lie ahead. Looking forward, he is featured by Carbon 12 Gallery at Art Dubai in April 2026, marking an important engagement with the UAE contemporary art scene and signaling the continued global reach of his practice.

Ivona Mirkovic met with the artist in his studio to capture the essence of his process and the nuances of his practice, while hube sat down to discuss the intersections of identity, materiality, and diaspora in his work.

hube: Much of your practice revolves around identity—both personal and collective. How has moving from Missouri to Nigeria and later to Brooklyn reframed the way you locate yourself within a global Black diaspora? How do those geographies inform your sense of belonging, or even the audiences you imagine for your work?

Anthony Akinbola: I think the beauty of the concept of diaspora is that it’s not subject to just one physical location or experience. I am a collection of my experiences and it’s these experiences that shape my idea of blackness. I hope people can see themselves in my practice, but ultimately I believe what’s more important is that they feel inspired to share their stories and contribute to the ever-growing pool that makes up this ‘global Black diaspora’. I feel like people don’t always appreciate some of the more banal parts of their lives, but it’s these things that create new and unique perspectives compared to the more sensationalised stories we tend to hear more often.

h: From a purely technical perspective, what has working with du-rags taught you about surface, tension, and modularity? Do they behave in ways that force you to adapt, and how do those limitations shape the outcome?

AA: Over the years I’ve learned more and more about the material and have been able to develop different techniques around working with it. I find myself constantly trying to push the limits of the material and what I can do with it, and I spend a lot of my time experimenting in the studio. Most of the time I don’t really know what I’m going to get until what I’m working on is finished, but I also think that’s the beauty of it; there’s an element of spontaneity I like. I don’t think I would be as interested if I knew what I was going to get.

h: How do your new flower arrangements mark a shift in your practice, and what excites you about this new direction?

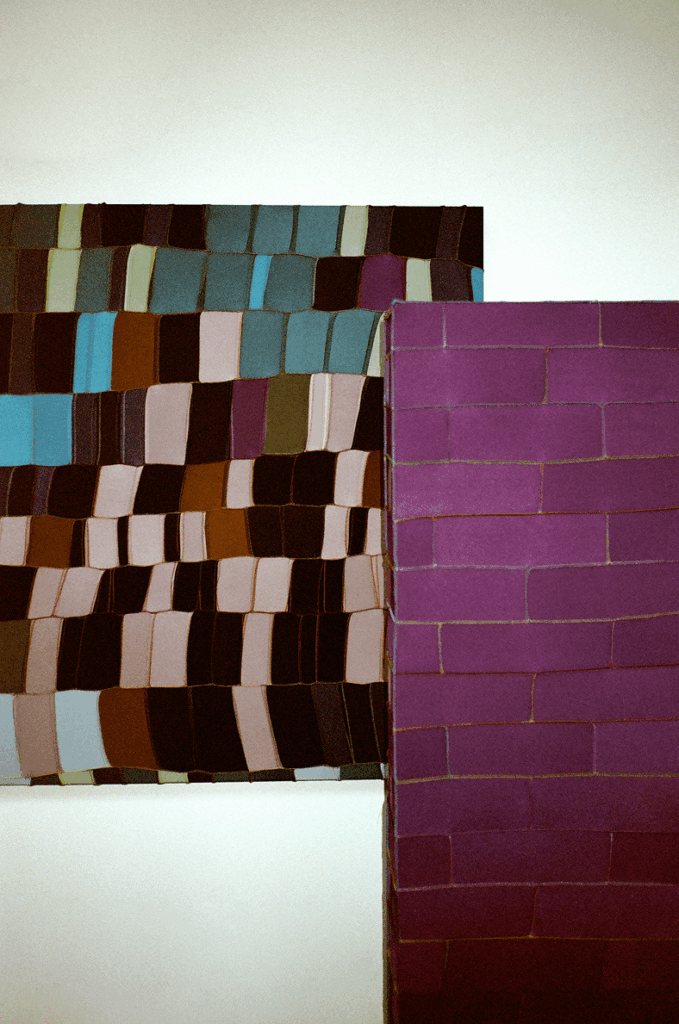

AA: The flower arrangements are a body of work that is still very new. I’ve made work that has referenced foliage but it was surface level, like the work was green and draped so by nature I would think of trees and leaves just by the way the material draped. What makes these works different is that I’m starting with the intention of participating in the art history of floral/garden scenes. For me these paintings are my offering to what many have done before me and add to the ever-evolving conversation of still life and landscape painting.

This exercises allows me to also push the limits of the material and expand the ways I can use it. For me each du-rag tail is a brush stroke or a mark of color, and it’s the accumulation of that mark making that creates a composition. I’m deciding to make a major switch from the works I’ve made over the past five years to this new style of working. Basically this is a new shift in the work, and I’m not going to be making the work I’ve been making the past couple years. I’ve learned what I need to learn from it, and now it’s the start of a new journey. I personally feel like each body of work needs a start and finish—all good things must end, and you need to be able to return to the cave and figure out how to make fire again. It’s important as an artist to constantly push yourself.

h: What feels truly beautiful to you right now—not just visually, but in energy or feeling?

AA: Wanderlust.

h: Having roots in Nigerian visual culture—renowned for its bold colours, draping, and geometric textiles—while being immersed in the American visual field, which often defaults to muted palettes, how do you think about negotiating or colliding these languages? Do you find yourself blending them, or creating a third space altogether?

AA: I don’t think much about palettes in relation to culture. A lot of my colours are based on what’s available. Because I’m working with ready-made objects, the colour is directly dictated by the market. Supply, demand and competition are the factors influencing the palette. Of course, I ultimately decide how these colours come together, but it’s more of a feeling to me. I put colors next to each other, and if it feels good, I move in that direction; if it doesn’t, I change it. It’s a visceral experience for me; it depends on my mood and how I’m feeling in the moment.

h: Collaboration, whether direct or through reference, seems to underlie parts of your practice. What role does dialogue with other artists, musicians, or writers play in shaping your trajectory?

AA: All art has an element of collaboration in it; we are all inspired by things that came before us and it finds itself in the work. I think artists like to run from this or deny this because they want to believe they’re doing something original. I don’t think being inspired makes the work less original. The things I’ve read, listened to, or seen will eventually come out in the work.

h: What does ritual mean in your practice—not only in terms of spiritual or cultural traditions but in the daily rhythms of making art? Do you think of the studio itself as a ritual space?

AA: My studio is just where I get my work done. Going to my studio to make work gives me a sense of direction; I think this direction is important for me or I start to get anxious. I don’t know if I would call it a ritual, but it definitely keeps me busy and engaged in a way that is necessary for me. Recently, I’ve been making brick motifs in the studio and it’s nice because I don’t have to think too much about it. There is a clear sense of direction for me in this act, almost as if there’s a utility to it. I go into the studio, spend the day sewing bricks together, I leave, then come back the next day and do it again. Maybe this is my current ‘ritual’.

h: As your visibility increases, how do you navigate the delicate balance between authenticity and market demands? Does the commercial framing of Black art risk narrowing its meaning, or can it expand its reach?

AA: I try not to think about the market in relation to my work; obviously it’s there, but I don’t think it’s helpful or useful to think about it too much. There’s work that I make for myself because I need to make it and need to learn from it, and there’s work that the art market has deemed as valuable and tends to sit more at the forefront. All the work I make is important to me, and it’s also work I enjoy making, and when I don’t feel like it’s feeding me anymore, I’ll move on to something else. I think any type of framing can expand or reduce the way in which the work is seen. I welcome all views and perspectives. I can only learn from them.

h: What role do audiences play in your practice? Do you imagine your work differently when it’s experienced in a museum, a gallery, or a community space?

AA: I feel like the audience brings their views and experience to the work in a way that activates it. I can only look at the work from one perspective and one experience because I’m one individual. An audience allows you to learn more about your own work because you’re seeing all the different ways it’s being experienced by people, and in turn I’m learning from their experience.

h: New York is relentless in its energy. How do you carve out moments of stillness or clarity to sustain your practice? Are there particular rituals, communities, or spaces that help you stay centered?

AA: A couple of years ago, I purchased a property in upstate New York which is essentially in the middle of the woods. It was one of the best decisions I could have ever made. Don’t get me wrong, I love the city, but I think every once in a while, you need a detox.

h: How would you describe the future in five words?

AA: As bright as can be.

Talent: ANTHONY OLUBUNMI AKINBOLA

Photographer: IVONA MIRKOVIC

Digital editor: ISABELLA MICELI