This September, the prolific visionary celebrated two decades of collaboration with Emmanuel Perrotin with solo exhibitions in Paris and New York. The two spaces featured a wide range of Arsham’s work, including his early sculptures and most recent projects, a new collaboration with Star Wars, and paintings created with a new impasto paint that Arsham developed to invoke the texture of Renaissance masterpieces.

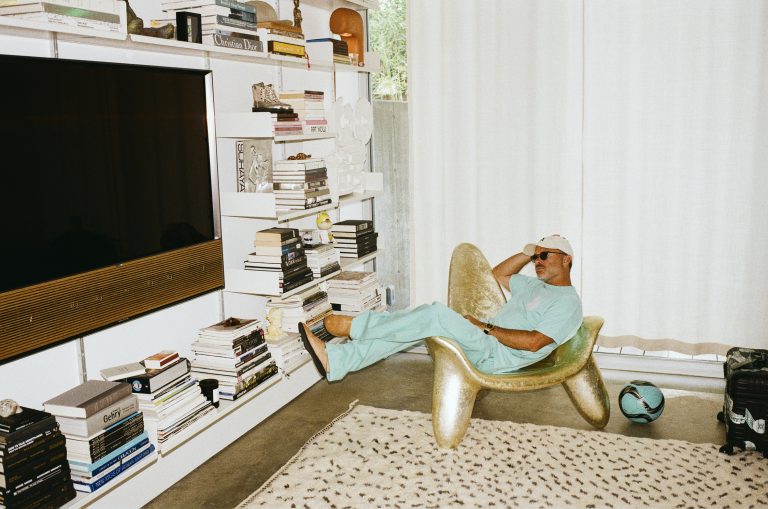

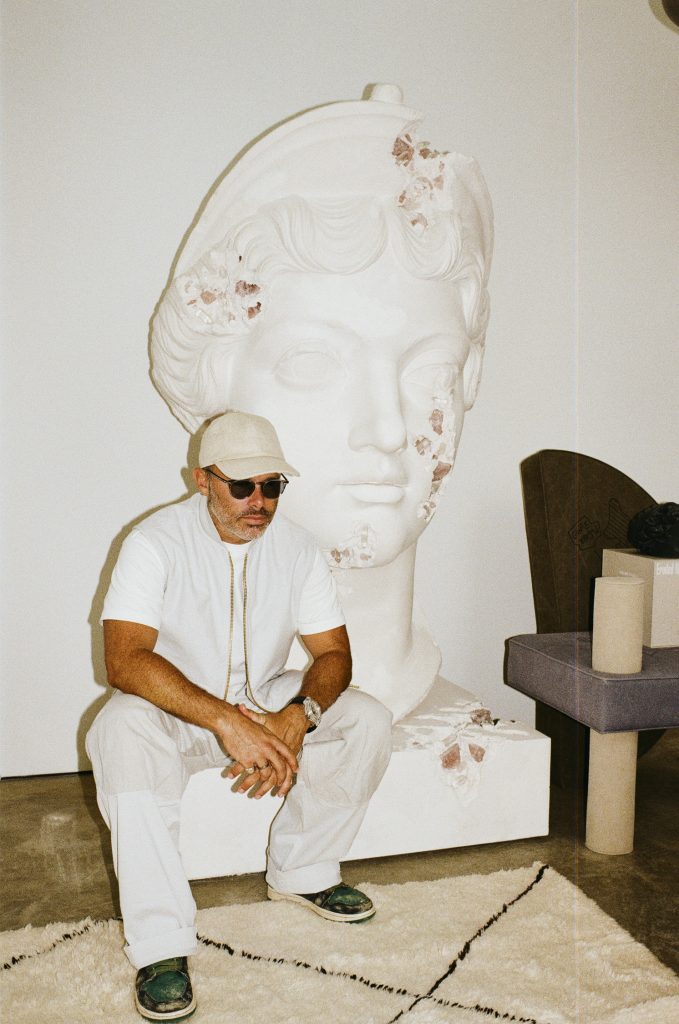

We visited Arsham at his home on Long Island; a 20th-century masterpiece designed by Norman Jaffe. The ephemeral, incomplete, and elusive beauty of Arsham’s work and the setting in which we met naturally led us to a conversation about Japan. Dive into our interview with Daniel Arsham as he shares his insights on beauty, collaboration, and the role of time in his creative process.

Photography by BRENDAN WIXTED

hube: Buddhist and Shinto philosophies have heavily influenced several Japanese aesthetic traditions. What is your perspective on the relationship between ethics and aesthetics?

Daniel Arsham: I’ve spent a lot of time in Japan over the last 20 years, and the attention that is paid to materials and the care in everything that is done in one’s daily life is something that I’ve paid close attention to. There’s a word, omotenashi, that is used in Japan. The literal translation is hospitality, but it really means care in everything you do, from the way you walk to the way that you might wrap an object in paper, the way you present food, the way that you hand an object to somebody. All these traditions have to do with attention, and I think our ability to understand aesthetics has a lot to do with the culture in which we live and grow up.

h: Is it possible to define beauty objectively, or does it exist solely as a subjective and individual perception influenced by irrational senses? Is there a concept of ultimate beauty that transcends cultural and personal preferences?

DA: Beauty is objective; however, I think there’s a constant of beauty that exists which, generally, humans can agree on. For example, objects from nature like the sun and water, and celestial bodies like stars and planets. I think beauty becomes subjective when it has a human hand in it and something outside of nature is the creator.

h: While a composer creates music alone, a choreographer and a dancer will collaborate closely to bring an artistic vision to life. In your perspective, what is the difference between such solitary and collaborative creative processes?

DA: I worked for many years as the stage designer for Merce Cunningham, the choreographer. In the 1950s, he began a process of separating dance from both the music and the visuals. Working with John Cage’s ideas around chance encounters in an artwork or a piece of dance or music, Merce would create a dance that was not linked to visuals or sound. So, in collaborating with him, I never knew what the dance was going to be. And I never knew what the music was going to be. I made my work independent of that. So did he and so did the composer of the music. So, all three of these elements were brought together to experiment. He liked to say that he might find things in this that he wouldn’t have otherwise found if he put his own intention or his own taste or choice into the music or the visuals. This was a great way to work for me. It was a bit terrifying as a 24-year-old when I began with him, but I learned a lot about collaboration and the ability of different art forms, when brought together, to create new experiences.

Time was such an element of Merce’s work, for example, he was able to stretch time, compress time, and sometimes his performances felt very long and other times very short, but it was all a feeling, the minutes would be the same.

h: The symbols and imagery employed in your work transcend cultural boundaries to create a visual language that seems almost universal. Do you believe art should be understood by everyone?

DA: I think art is for everyone. And everyone is an artist. Every child is an artist. I think we, as a culture, tend to lose that ability to communicate in those ways as we get older. Artists are striving to hold on to that ability to use creation as a vehicle for communication. And I try to make work that can speak the same language wherever it is. In Japan, New York, Paris, São Paulo, Sydney. The work sort of means the same thing and has the same reference points for people.