The events fall on a Harvest Moon. A time, they say, is for manifesting our deepest, darkest desires. Paris is still hungover from the end of Fashion Week, where monumental things have happened. Matthieu Blazy has debuted at Chanel, unveiling his first collection beneath the domed ceiling of the Grand Palais, over a galaxy of planets. A universe has been created. A new and exciting one for the world of fashion.

Across the city, another universe unfolds inside the dome of the Bourse de Commerce. The exhibition Minimal is, on the surface, an ode to minimalism. But after contemplating it more deeply, something in it felt urgent. Though we’re not sure if it was intentional on the part of curator Jessica Morgan, Director at the Dia Art Foundation in New York. The show felt to us like a message. An urgent one in these precarious, trying times of genocide, war, social media overload, relentless overconsumption, and persistent unemployment. As we, the journalists and critics, took our photos for our own social media accounts (yet another small ritual of consumption), the exhibition opened with a floor of candies, an installation by Félix González-Torres, and a series of Robert Ryman’s white paintings. A perfect introduction that begs questions. Are our lives of consumption so sweetly deceptive? And how pure are we with all our worldly desires?

Above, the floors unfold like campaigns, dedicated to Mono-ha (an artistic movement from late 1960s Japan that translates to the School of Things), Balance, Surface, Grid, Monochrome, and Materialism. Themes that echo something profound about our relationship to our physical realities, and, perhaps more intimately, our identities. Bronze sculptures by Susumu Koshimizu for one sit like radical meditations on materiality. Nearby, Senga Nengudi’s Water Composition series, which curator Morgan describes as a response to pressure and gravity, shows the same tension in different forms. The liquid, sealed in plastic, collapses heavily on the floor, ropes holding it like tired, injured limbs, almost like a representation of the weight we’ve created for ourselves through what we consume. It functioned as a challenge, almost confrontational, a prompt to provoke reflection.

On Materialism, Michelle Stuart’s Sayreville Strata Quartet (1976), realized using earth pressed directly onto muslin-backed rag paper, stands strong on the wall. The work is arresting; you cannot miss it. Marden Hassinger’s thirty-foot River Floor sculpture stretches across the gallery, using shipping ropes to tell the story of transatlantic voyages of enslaved Africans to the Americas. The piece calls attention to the waterways that facilitated the slave trade, and perhaps to the destruction of life and labor through industrialization.

Below, throughout the basement floor, the section Light emerges as its own. In the 1960s and ’70s, artists began using light as a primary material which apparently was a response to the visual noise of neon signage and the unavoidable presence of advertising in our lives. Dan Flavin’s alternate Diagonals of March 2 glows in red and yellow fluorescent light, two colors in combination known in color psychology to boost urgency, sometimes appetite. Chryssa, one of the earliest artists to translate sculptural form into neon, sought to “embody all the emotional and nervous energy of contemporary visual communication.” According to the Dia Art Foundation, her vastly underrecognized body of work “bridges Pop, Conceptual, and Minimalist ideas of art making.” Gates of Times Square, part of her series inspired by the iconic New York landmark, vibrates with the same electric message: light can energize and seduce, but at its worst, lure and distract, getting us lost rather than found.

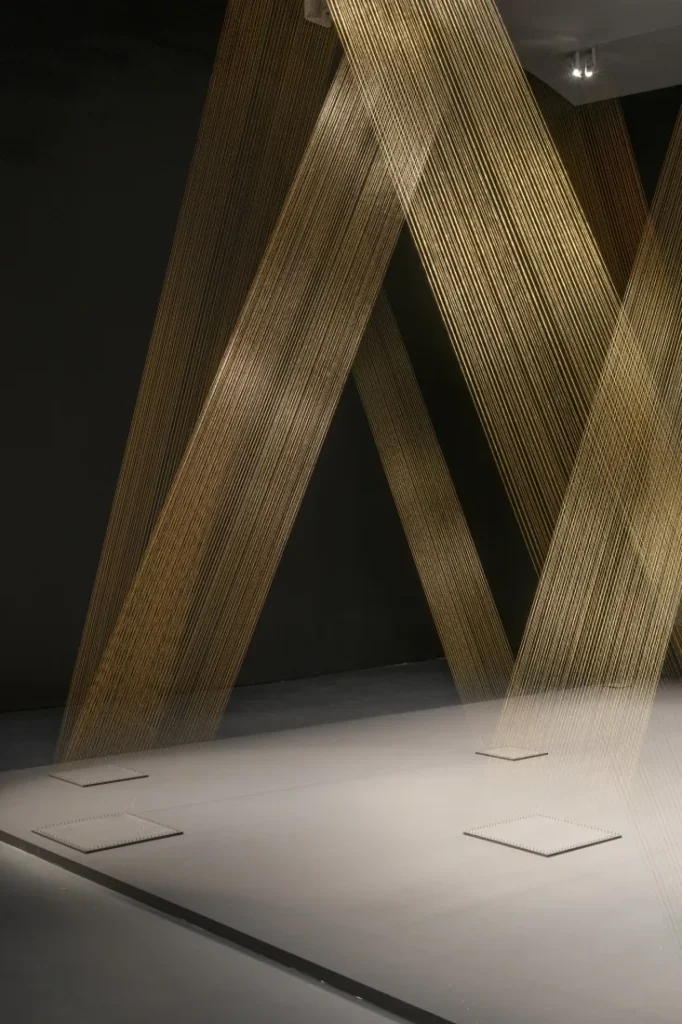

Two artists are given their own galleries: Agnes Martin and Lygia Pape. Canadian-American artist Agnes Martin described her work as an expression of inner states, calm and clarity, rather than representations of the visible world. Her oil-on-canvas piece White Flower quietly reveals the need for restraint. Meanwhile, Lygia Pape’s gallery places discourse on social politics at its core. A video of one of her performances is on view, alongside Ttéia 1, C an installation of gold strings that shimmers with quiet precision. The work can be read as the epitome, or even pinnacle, of desire: our endless attraction to gold, to status, to material beauty.

Just beyond the center, along the hallways, hang a few of On Kawara’s date paintings. Minimalist meditations on the passing days. Is the exhibition reminding us that no investment is more precious than time itself?

Meanwhile, beneath the Bourse de Commerce’s magnificent dome, sit Meg Webster’s five installations: Cono di Sala made of salt, Mother Mound and Mound shaped from soil, Wall of Wax crafted from beeswax, and Circle of Branches assembled from diverse branches, all materials of which have been locally sourced reflecting her enduring focus on materiality and ecological awareness. In Mother Mound, the soil transforms over time, developing damages shaped by the environment itself. As the visit draws to a close, something becomes clear: the curation, almost instinctively, positions Webster’s works as the antidote to our excesses. The remedy is there—in nature, and in time.

Photography by FLORENT MICHEL, courtesy of PINAULT COLLECTION

Words: LIZ BAUTISTA