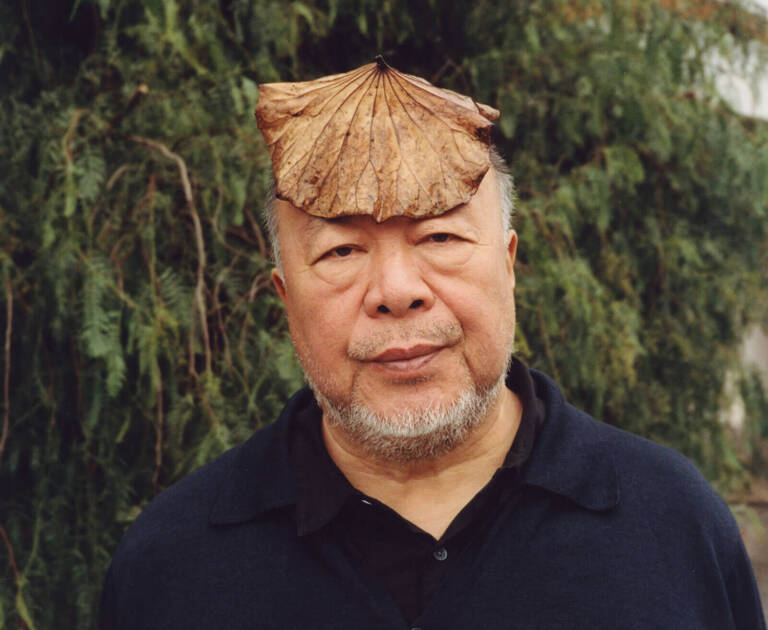

Does freedom demand courage, or are the two inseparable? For Ai Weiwei, they are sides of the same coin. The artist has become world-renowned for transforming commonplace materials, objects and actions into powerful political and social statements, revealing their meaning through formal subversion and scale: One surveillance camera sculpted from marble. Three Han Dynasty urns, dropped. Fourteen thousand life jackets across the facade of Berlin’s Konzerthaus. One hundred million hand-crafted porcelain sunflower seeds scattered throughout the Turbine Hall at Tate Modern. Ninety tonnes of steel rebars, recovered from the rubble of the Sichuan earthquake, straightened by hand and displayed across the ground floor of the Royal Academy of Arts in London.

Spanning installation, activism, and investigation, Ai’s boldly provocative and conceptually rigorous work has earned him international acclaim while provoking intense scrutiny in his homeland. His experience as a dissident artist, coupled with that of his father’s exile, have shaped a practice that is art and activism: a platform for resistance and truth that resonates across East and West.

Join us for an interview with Ai Weiwei, where he explores the power of objects, the role of time in artistic legacy, and why creativity is always linked to destruction.

hube: Is a connection between an artwork and an idea necessary? Can art exist without ideas, narratives, or meanings?

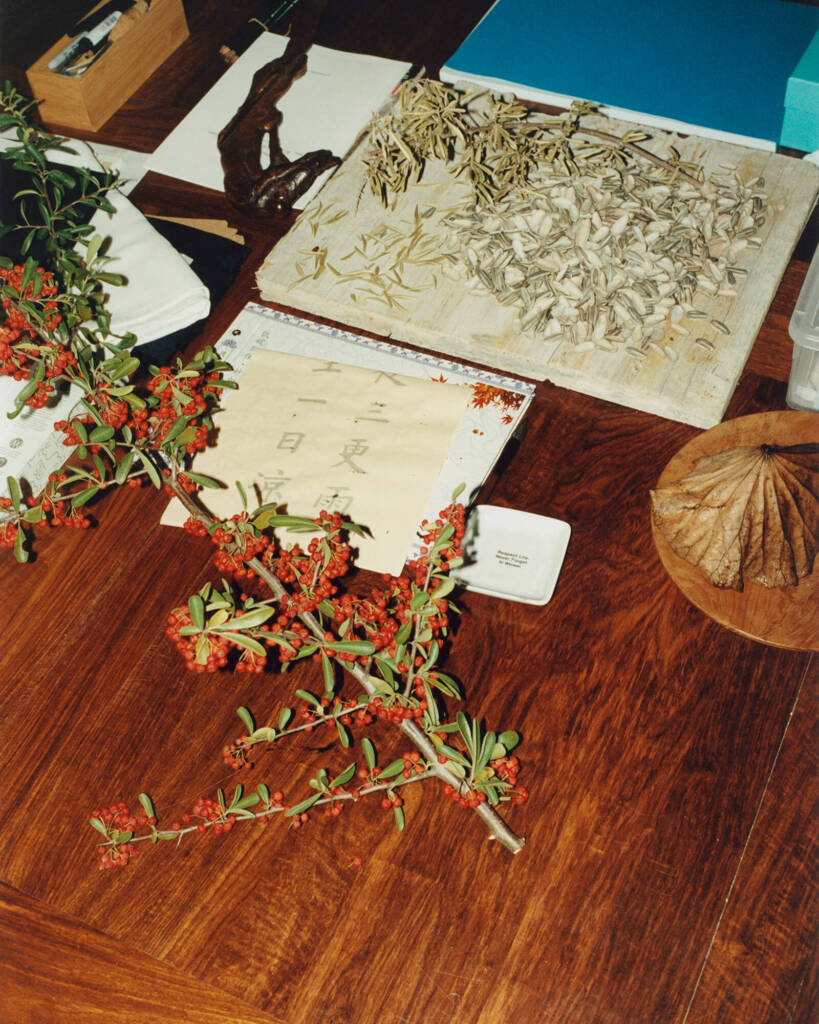

Ai Weiwei: All human behaviour, including what we refer to as creative activity, is inherently tied to the transformation of emotions into form. This process of transformation is, in essence, the formation of ideas. When an idea takes on a concrete shape, we can consider it a complete, rational decision. In most cases, artworks arise from a guiding rationality—whether aesthetic, ethical, or political. Yet, if we examine creation more closely, we see that the process of forming ideas gives new artworks their meaning and existence. Art cannot be separated from ideas, nor can it be detached from narrative or value. It is similar to the flow of air and water, which cannot exist without temperature, currents, or geographical characteristics.

h: The symbolic meanings of objects are often associated with religious or mythological thinking—a refusal to acknowledge the rationality of the world. How do you see the connection between reality and imagination?

AW: If we view the relationship between imagination and reality as one between concreteness and emptiness, or between presence and absence, this relationship becomes clearer. All the ideas we hold—whether based on objective reality or mythological and religious concepts—are narratives we create to fill the space of imagination. Yet, as humanity explores the world, it becomes apparent that the universe is far greater than our senses or cognition can fully grasp. I thus believe that what we call “reality” is simply a relationship between positive and negative forces, existing simultaneously within what we imagine as space. Both coexist.