“Hell is Real” flashes across the canvas in one of Amanda Ba’s 2023 paintings, a lone female figure racing down a highway on a motorcycle. It feels like the entry point to a world you think you recognize: cinematic, restless, apocalyptic, yet quietly layered with reflections on national identity. Ba’s canvases resist easy definition, sighs suspended in pigment, questions that refuse to settle. Look closer, and the work opens up.

Ba logs onto Zoom after a detour to an AMC theater in Midtown, where she’d just picked up a Tamron lens off Facebook Marketplace. A detail that feels fitting: practical, funny, slightly cinematic. In our conversation, she talks about the motifs running through her paintings, how watermelons became a loaded symbol, and why New York is still the only place she wants to paint.

hube: You often speak of an apocalyptic undertone in your work.

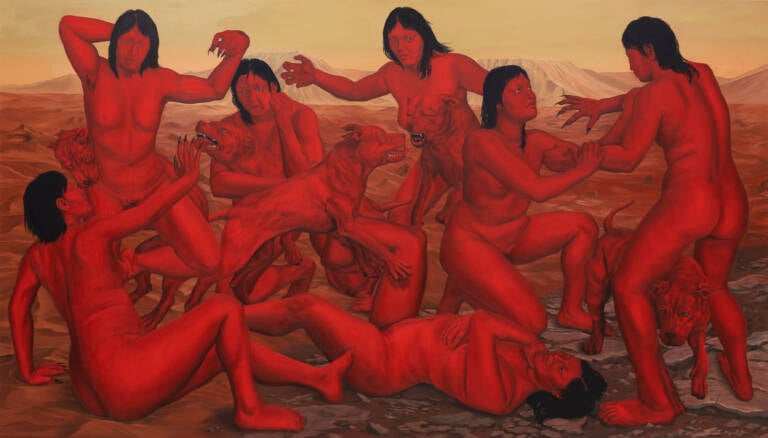

Amanda Ba: I keep motifs in an arsenal: things I’ve researched for past shows that I can redeploy as needed. In my last show, which was about sports, that tone wasn’t as present; I was working with a different idea. But my first solo show in London had Titanomachia, a frieze-like painting of figures and dogs tussling. The background could read as primordial or dystopian. It suggested creation, but also something Martian, like a desert in the future.

I’ve never been overly concerned with chronology. My figures and environments are archetypical, so desolation can feel like the past or the future. I’m not trying to declare “the apocalypse,” but my next body of work, circling violence, might bring that tone back.

h: Your early life spanned vastly different geographies, from Columbus to Hefei to New York. Have those shifts in place and pace taught you to perceive time or space differently?

AB: My location definitely factors into my work subconsciously, but the effect is usually delayed. I need contrast to reflect on what a period of time meant. Splitting my time between Ohio and my hometown in China gave me a sense of what else is going on outside of big cities. Sometimes I’m glad I didn’t grow up in New York; though I used to be really jealous as a teenager, growing up in Middle America probably made me friendlier and helped me understand why sociopolitical trends in America tend to drift the way that they do. And most of America is like Columbus, where it’s harder to access cultural pipelines. There, the internet becomes your main source of information.

On a larger scale, my childhood made me more inquisitive about global relations, especially between China and America. The average American is starting to sense China’s development on a different political and historical model than the West expected. I’m always thinking about perspectives on historical timelines, and how we have come to think of our national identity, versus someone else in a different place, thinking of their national identity. And philosophically, time is colonial; standardized time was developed with British naval exploration to standardize shipments. Before that, clocks relied on gravity, and didn’t work on ships, which led to competitions to invent a stable timekeeping device at sea. You can trace that to the Atlantic slave trade. So, time is a big question, too big for me to fully answer, but that’s where my thoughts go.

h: Do you feel people in those non-urban environments are more attuned to their surroundings, maybe even closer to a posthumanist way of being? Or is that just a romantic idea?

AB: It’s a really hard question, as there are different measures for what it means to be “attuned to your surroundings”. People in big cities all want and strive for something, which is why we choose to live in places that are so difficult in many ways. But there’s connectivity, and through collective efforts, scenes and communities develop, and you can situate yourself in a web. In more suburban places, things come to you by proximity, whereas in New York, everything is in a ten-mile radius, so you have more ability to choose who you spend time with. In small towns, you engage with whoever’s around, valuing everyone’s presence more because your social pool is smaller.

Blueprint Titan

Developing Desire exhibition at the JEFFREY DEITCH GALLERY, New York City

Courtesy of AMANDA BA

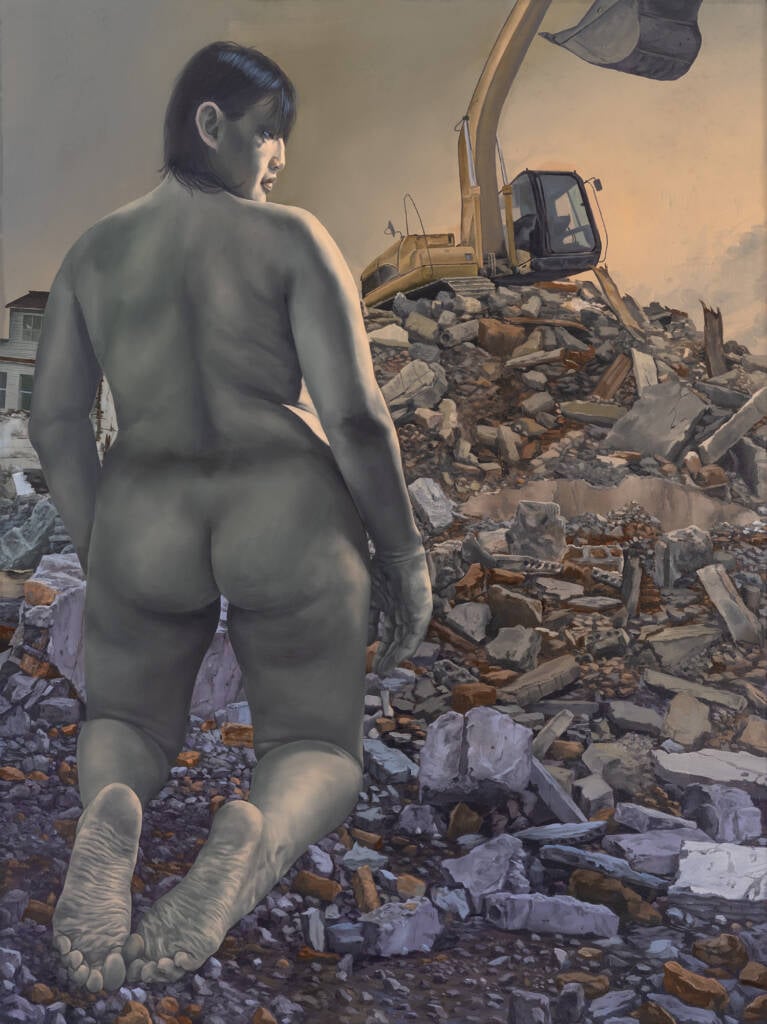

Rubble

Courtesy of AMANDA BA

Installation view of More Future Triptych, view from the Developing Desire at the JEFFREY DEITCH GALLERY, New York City