Getty Images. Courtesy of THE WORLD AROUND

Getty Images. Courtesy of THE WORLD AROUND

Getty Images. Courtesy of THE WORLD AROUND

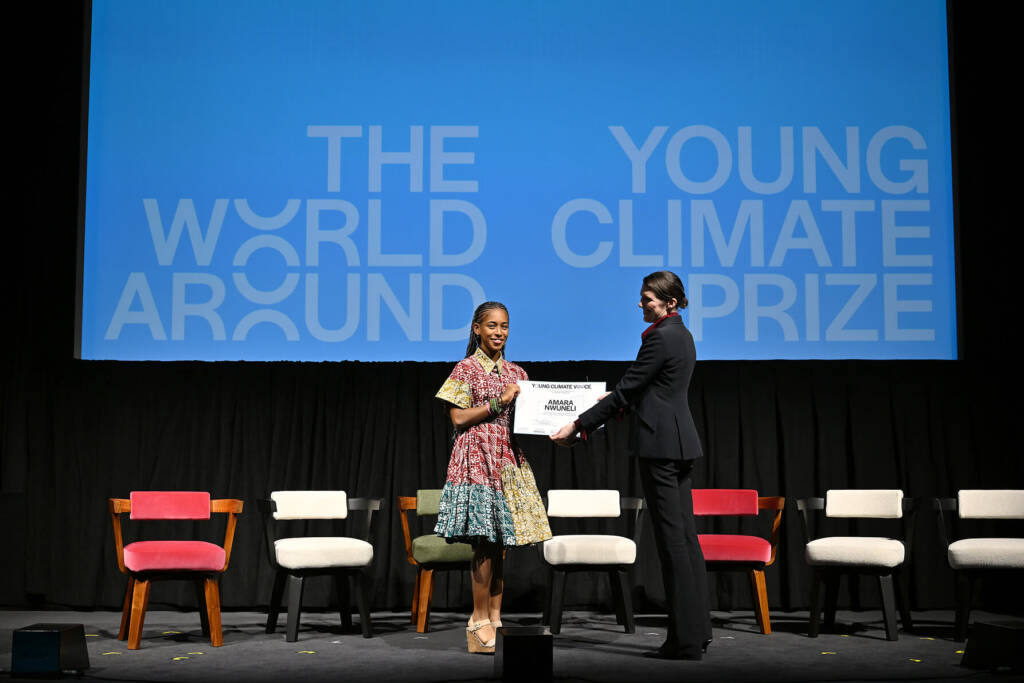

Beatrice Galilee, internationally recognised curator, writer, and founder of the global non-profit The World Around, has pioneered the dialogue around architecture and culture in a career spanning over twenty years. Having worked as editor of Icon Magazine, creating revolutionary pieces like Architecture Without Buildings, to curating events and numerous architecture biennales—eventually moving on to serve as the first-ever curator of contemporary architecture at the revered Metropolitan Museum of Art, Galilee has created a sharp and action-driven critical discourse about architecture in connection to culture and the future of climate action. Since 2019, she has focused on her non-profit The World Around, organising summits bringing together voices from around the world with the common goal of amplifying sustainable innovation with urgency. With a prioritisation of education beyond borders, Galilee and The World Around launched the Young Climate Prize in 2023, an initiative partnering young innovators from all over the world with mentors and resources to broadcast and manifest their ideas for the ‘now, near, and next’ of climate action.

hube: You were the first-ever curator of contemporary architecture at The Metropolitan Museum of Art—an institution deeply rooted in history. How did you go about shaping this unprecedented role? Were there particular challenges or freedoms that came with that responsibility, and what legacy did you hope to leave?

Beatrice Galilee: When I arrived at The Met, invited by Sheena Wagstaff and Tom Campbell, the role itself was wide open—there was no precedent, no playbook, and no expectation beyond the fact that architecture had historically been under-represented in the museum’s programming. That freedom was exhilarating but also daunting. I approached it as an opportunity to experiment: to bring the voices of contemporary architects and designers into dialogue with the museum’s vast collection and with contemporary global issues. One of my priorities was to reframe architecture not just as an object or style, but as a lens for understanding the world—politically, environmentally, socially. I did this through collaborations with contemporary artists, photographers, sculptors and film-makers for whom architecture represents those ideas. I brought work into the collection that I think was really meaningful and presented a public programme series that brought thousands to the museum to hear emerging voices and fresh, global ideas in the architecture world. My legacy, I hope, is that I left behind a clearer path for architecture to exist in major art institutions as a living, urgent, and deeply relevant cultural practice.

h: In your opinion, does architecture inherently look toward the future, or is it more often a dialogue with the past? How do you personally balance those two temporalities in your thinking and curatorial work?

BG: I see architecture as living in constant conversation between past and future. This is why our motto at The World Around is ‘architecture’s now, near, next’! Every building is a palimpsest—layered with historical context, cultural memory, and material histories—yet it inevitably projects into the future, shaping how we live and interact for decades to come. In my curatorial work, I aim to hold those two poles in tension. For example, I’m interested in projects that revive traditional building practices through contemporary needs, or that take a critical look at modernism through the lens of climate responsibility. To me, it’s not a question of choosing one over the other, but of curating that continuum.

h: Architecture often acts as a mirror—reflecting cultural values, political systems, and environmental conditions. When traveling, what have you observed about how different societies integrate contemporary architecture into their cultural landscapes? Is there a particular city or encounter that left a lasting impression?

BG: While I call New York my home, I’ve lived in London, Beijing, Berlin, Lisbon, and worked at length in major cities such as Gwangju, Milan, and Shenzhen. The type of travelling I’ve done helps me see that contemporary architecture is never neutral; it always reflects and refracts the values, histories, and urgencies of a place. In Tokyo, for example, new buildings are absorbed into a fabric of perpetual reinvention. Change itself is tradition, and architecture becomes a visible expression of a culture comfortable with transformation.

In Europe, by contrast, the conversation feels more heavily focused on memory, preservation, and reuse. Too many structures are still demolished unnecessarily, but the most compelling projects show how reuse can be both culturally resonant and ecologically powerful. Berlin, where I lived for several years, remains the most striking example: the Reichstag’s democratic rebirth, David Chipperfield’s restoration of the Neues Museum, and Arno Brandlhuber’s reimagining of the Mäusebunker all demonstrate different ways of negotiating history through design. They carry the memory of war, politics, and collective trauma while pointing towards new futures.

What makes Berlin even more relevant today is how these practices are being echoed and amplified at the level of civic policy. The HouseEurope! campaign, for instance, is a citizen-led initiative that seeks to establish a legal ‘right to reuse’ buildings across the European Union. By calling for tax reductions on renovation, fairer evaluation criteria, and the recognition of embodied carbon in existing structures, it reframes architecture not only as a cultural practice but as a legislative priority. This intertwining of design, politics, and activism feels especially urgent now. It underscores the idea that architecture is not just a mirror of society but a tool for shaping what we collectively choose to value, preserve, and imagine for the future.