Richard Magee’s work discusses the interplay between surface and meaning, where the canvas transforms from a mere backdrop to a metaphorical body. From his exploration of memory to his innovative use of technology, Magee’s art offers a reflection on the relationship between creator, object and observer.

He is among the first artists showcased by the Corinthian Contemporary Art Partnership (CCAP), a foundation created in 2022 by Charles Bromley to nurture new talent, with works like Channel Tunnel ’94. CCAP fosters rising artists by exhibiting their pieces in members’ homes and partnering with curators and galleries, blending traditional art collecting with modern promotional strategies, positioning artists like Magee within a vibrant global art scene.

hube: Your artwork often incorporates unconventional materials like plaster and handkerchiefs. What inspires your choice of materials, and how do they contribute to the narrative of your pieces?

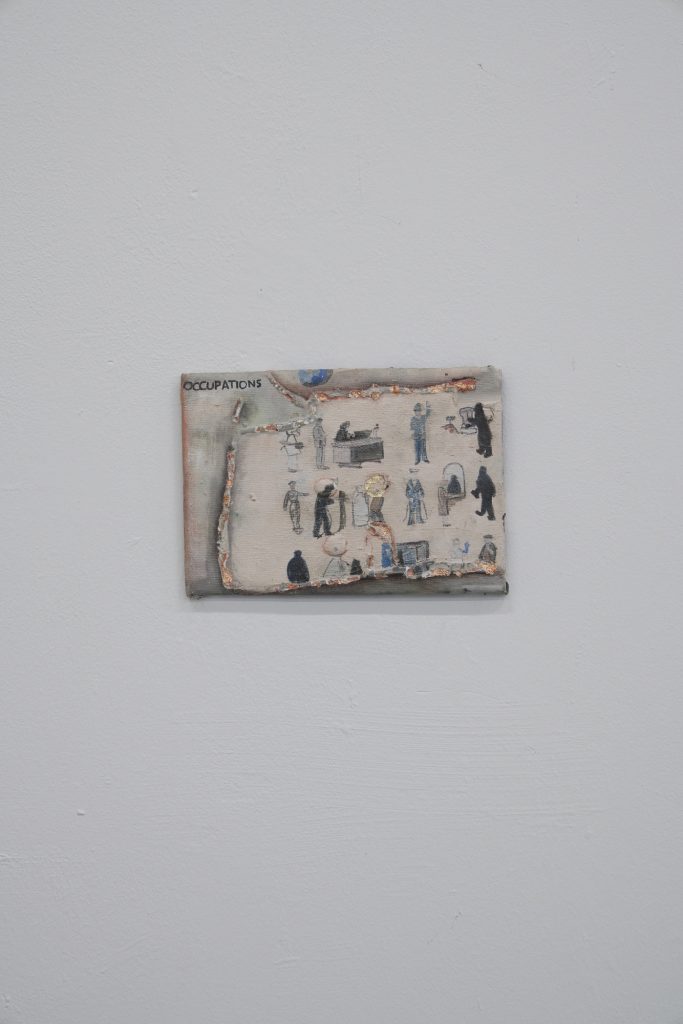

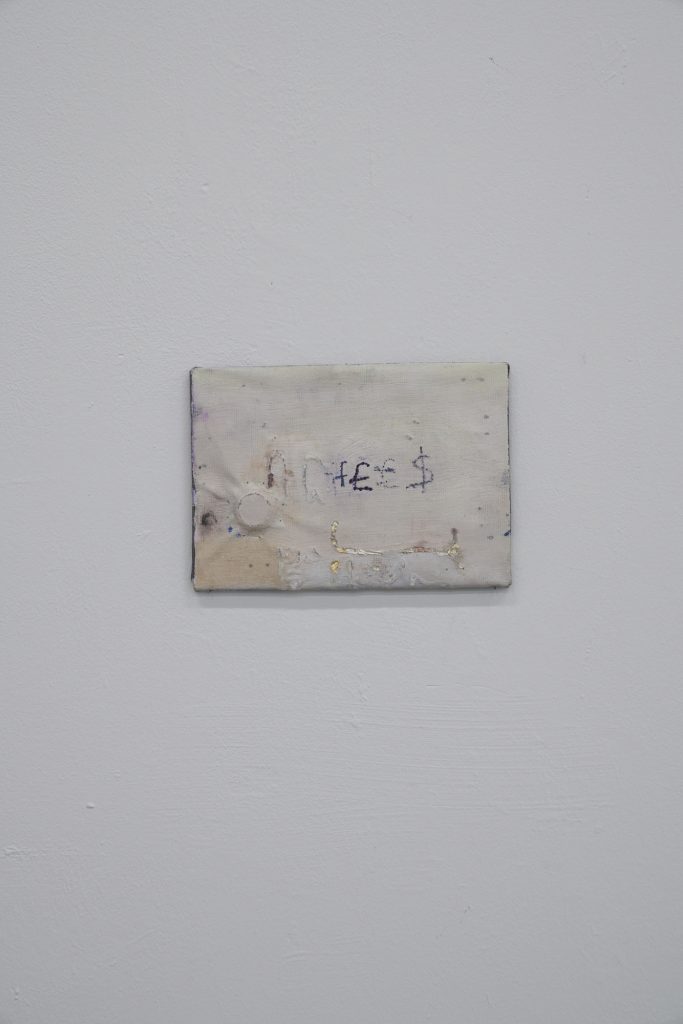

Richard Magee: The white canvas is already a defined surface. Once aware of that, it’s a small step to think that surfaces can problematise or seem more appropriate for different works. Sometimes, I’m interested in the canvas being presented as a sort of substitute body. My small, flesh-coloured, textured Brief Mark series should be read ontologically as something like pockmarked skin.

h: The Brief Marks series features postage stamps on paper. What are the conceptual origins of this series, and what is the meaning of the piece?

RM: ‘Briefmark’ means postage stamp in German, and I collect stamps, but only from the year I was born. I organise them on pages with broad themes like children, animals, or landscapes. They’re interesting to juxtapose or serve as time capsules of ideas from a certain time and place.

But… the Brief Mark series is different. It’s a loose title for small paintings, around 12 by 18 centimetres. These are interchangeably shown alongside a portrait where the space at the back of the head is missing.

On a wall, the little paintings look like thought bubbles coming from the figure’s head. They visualise the kind of procession of thoughts we have all day but barely notice. The head painting doesn’t change, but the small ones can react to the context in which they are shown.

The title introduces a situation where small ideas and observations, which wouldn’t normally be ‘enough’ for me as larger paintings, can exist. For example, how ‘war mega’ in German is saccharine – ‘Yeah, that was super’ – but for English speakers, the phrase sounds sinister.