For the nineteenth-century French essayist and art critic Charles Baudelaire, sin functioned as a sensory appetite. “The unique and supreme voluptuousness of love,” he wrote, “lies in the certainty of committing evil, and men and women know from birth that in evil is found all sensual delight.” Baudelaire understood such extreme sensations—those that puncture and punish our lives—as reckless yet rewarding: an escape from the inertia of not feeling at all. That compulsion to confront an ugly truth sits at the heart of the work of the London-born, Marseille-based artist Dominique White.

Winner of the 2022–2024 Max Mara Prize for Women, White’s work has been presented concurrently at Whitechapel Gallery, London, and Collezione Maramotti, Reggio Emilia. Her sculptures appear as though salvaged from the sea—stranded, scarred, and burdened with histories they refuse to explain. They confront brutality and beauty alike, while insisting on what White has described as her own “blackness”: not as representation, but as lived force. If her collapsing forms suffocate in their silence, denying easy legibility, it is because White is willing to reach inward—to draw on energies of anger, grief, and resistance that are as unsettling as they are generative. Spirited when speaking of identity and freedom, and of “living a nomadic life,” she seeks an abstraction that ruptures inherited narratives, unforgiving of what has already been recorded. If identity politics is central to White’s articulation of her work, the sea becomes its accomplice, rewarding this position with visual and material riches. Her sculptures spill outward onto the floor, as if severed by the sea itself. Reflecting on a lifelong connection to water and a sustained fascination with shipwrecks—vessels that, like human beings, retain layered histories, often preserved by immersion—White destabilises the romantic pull of maritime imagery. Sea and sand may initially conjure the idyllic, but she compels us to sink unceremoniously into their depths: to be cut open by fishhooks and weighted anchors, confronted by their looming shadows.

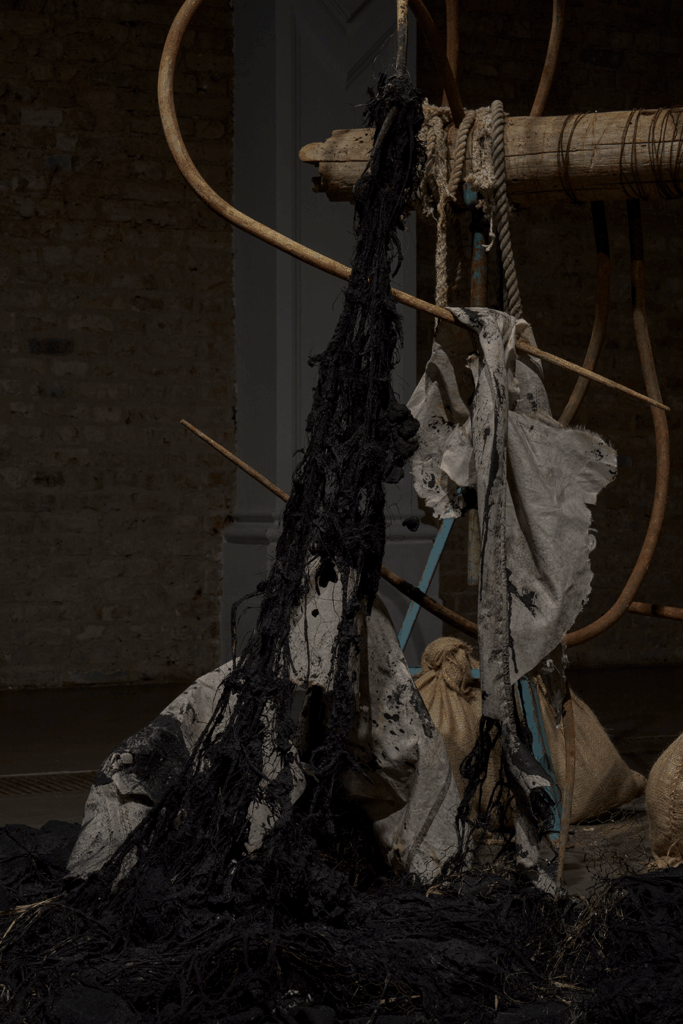

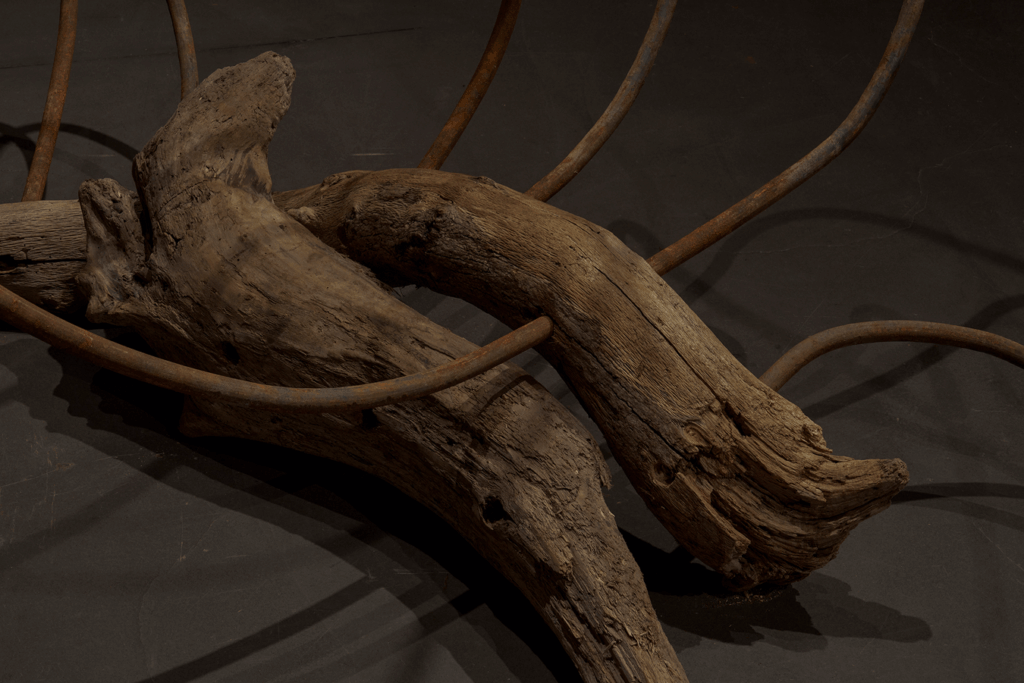

White’s materials, gathered from shoreline detritus, combine weathered natural and industrial elements—wood, metal, canvas, plastics, pigment—brought together in states of abrasion and decay. In her hands, they impregnate one another, as though death itself has stripped them of fixed identity. Yet, as Baudelaire proposed, such acidic appearances give way to a deeper beauty. These works attempt to seize time: to hold fragments that have not yet fully dissolved.

Rescuing these remnants from the sea’s appetite, White assembles them with equal attention to politics and poetry. Her fragile configurations propose fear as a legitimate emotional register—one that, as she argues, “has to be faced.” Encountered as though at night, when the senses sharpen and natural light is swallowed by darkness, her works operate in a heightened state of anticipation.

Uncertainty, for White, is fundamental. “The sea,” she has said, “is a site of impossibility—a flattening of time and a rejection of order.” This logic materialises in her sculptures’ apparent disorder. Yet they are far from chaotic. Iron rods scribble into space, mangled yet upright; skeletal forms hover above torn fabrics that stain the floor beneath them. To look at one of White’s works is to witness an incident—a body breached, its blood thrown outward, its breath faintly illuminating the dark. Historically, these works resemble no established sculptural lineage. They neither mimic reality nor seek to fill space in order to ennoble it. Instead, they appear riddled with grief, as though on the verge of rot. It is precisely this tension—between balance and brutality—that White sustains deliberately. As she has explained, she is invested in disrupting the power dynamic between object and viewer. Sculpture, she suggests, has long been conditioned to privilege the audience: to remain inert, elevated, obedient. In her work, menace emerges from fragility. Approach too closely, and the object may collapse—or harm you. Like the artist herself, these works are not passive. To encounter them in situ is to walk the seabed, confronting fear without the promise of resolution.

Dominique White has an upcoming solo exhibition at Kunsthalle Basel (CH) titled All Great Powers Collapse from the Centre, which will be open from 13 February to 17 May 2026.

Rajesh Punj: With exhibitions concurrently in London and Reggio Emilia, where are you based?

Dominique White: For the past two years I’ve been pretty much nomadic, because it’s been the easiest way to produce work. Even during the height of the pandemic, it felt easier to push myself creatively—I spent three months alone in Norway. Now, I’m based between Marseille and Essex, England.

RP: You have studios in both cities?

DW: I did before, but I’m moving—hopefully to the French countryside—to have more space. This is always my problem: I move into a studio, and within three months it’s completely full. You can have as many shelves as you want, but if one work is three or four metres long, and you’re making five shows a year, there’s simply not enough room.

split obliteration, 2024

Courtesy of VEDA and DOMINIQUE WHITE, photography by MATT GREENWOOD © ABOVE GROUND STUDIO

ineligible for death, 2024

Courtesy of VEDA and DOMINIQUE WHITE, photography by MATT GREENWOOD © ABOVE GROUND STUDIO

split obliteration, 2024

Courtesy of VEDA and DOMINIQUE WHITE, photography by MATT GREENWOOD © ABOVE GROUND STUDIO