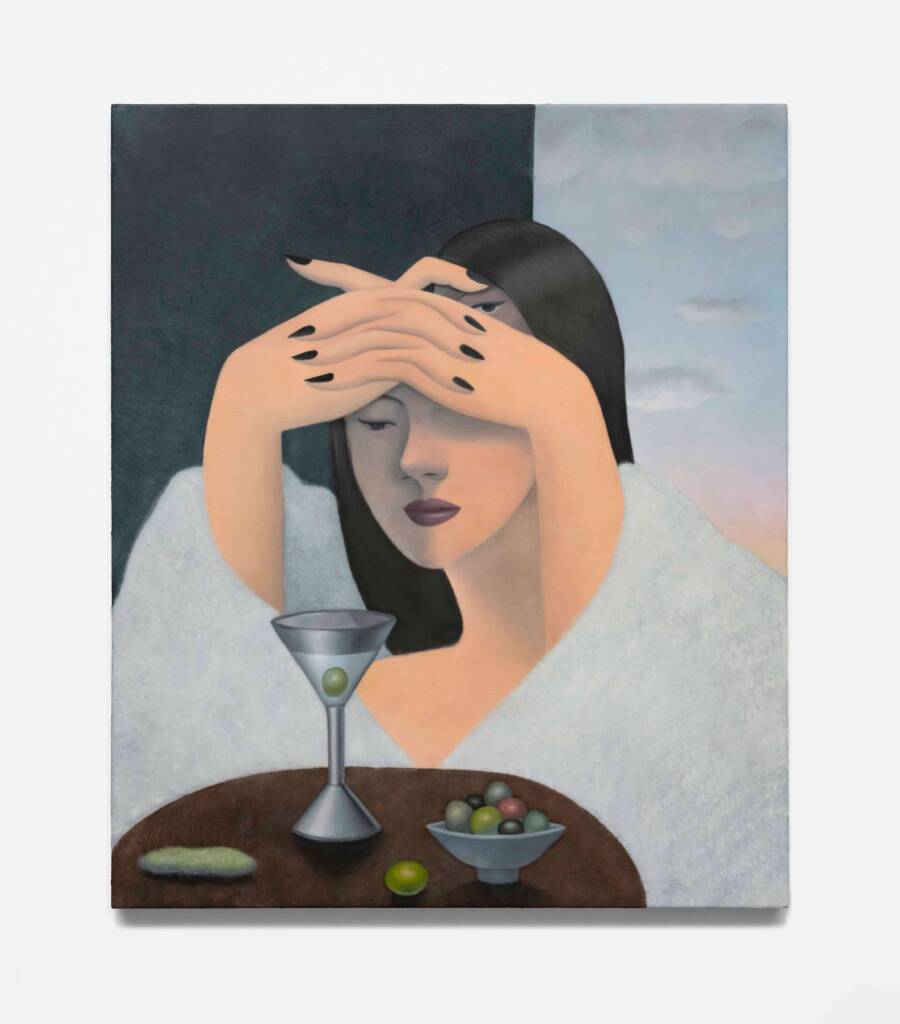

Woman with Cocktail, Olives, and Caterpillar, 2023 – 2025

Courtesy of GAHEE PARK and PERROTIN, photography by PAUL LITHERLAND

Room for Reflection, 2025

Courtesy of GAHEE PARK and PERROTIN, photography by PAUL LITHERLAND

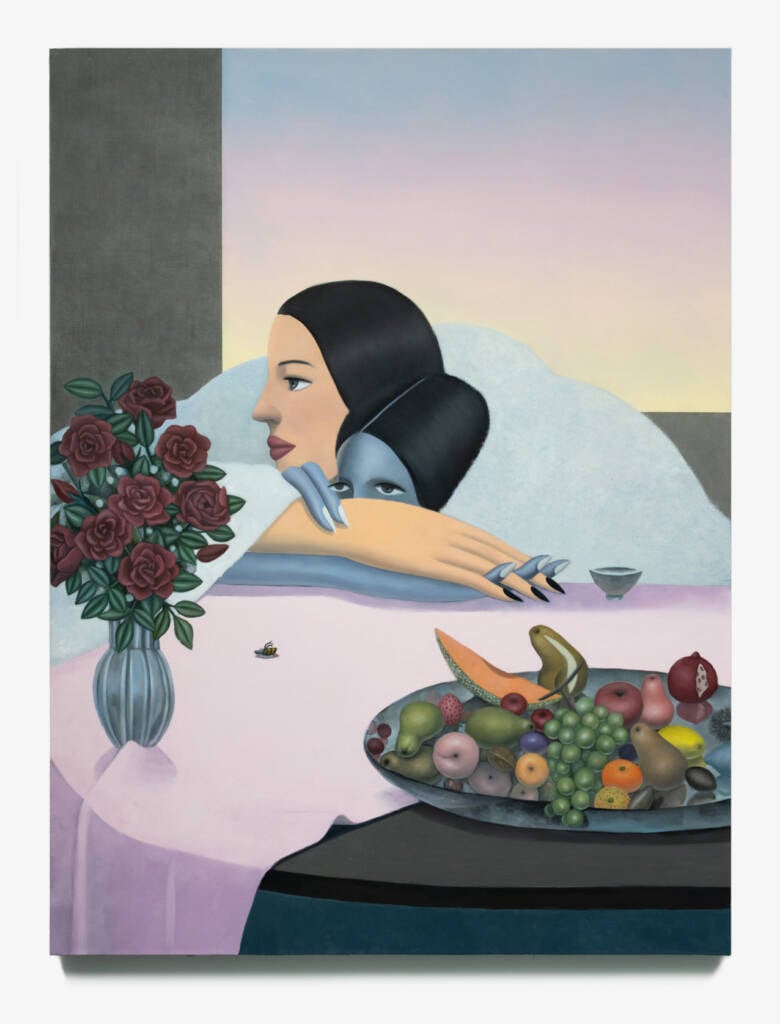

Blue Thoughts, 2023 – 2025

Courtesy of GAHEE PARK and PERROTIN, photography by PAUL LITHERLAND

Working in a vein of contemporary surrealism, GaHee Park’s paintings take their viewer into a corner of her mind, one that overlooks the sea. Half-entrapment, half-hallucination, the works speak in delicate tones, layering perspectives with relatives—whether it be including a painting within the painting, or is it a window? Guided by her distinctive artistic gaze, her focus can range from a still life that is anything but still, time rushing over a bowl of fruit on a cloth-covered table, to depictions of eroticism that feel mundane in the soft dreamscape she’s built. In this interview, hube speaks to Park about growing up Catholic, her likeness seeping into her work, and how time and space are often equivalent to memories and fantasies.

hube: You’ve lived between South Korea, the US, and Canada, with each country carrying their own cultural and visual codes. How do those overlapping cultural textures shape your artistic gaze? Do you feel like an insider anywhere or is that ambiguity part of your artistic identity?

GaHee Park: Maybe I’m stuck in between various places. Even within the US, I have lived in Miami, San Diego, Philadelphia, and New York—a lot of the ambiguity in my work comes from processing and digesting my experiences in these different places. Growing up in Seoul was frustrating for me as a kid. I have some good memories of my time as a teenager, but I also have many traumatic memories that can be overwhelming at times… adults hitting children was legal back then, in schools etc., and I was often exposed to violence.

When I transferred from my Korean art school to do my BFA at Tyler School of Art in Philadelphia, I felt kind of invisible, which was great in a way, but pretty lonely as well. In undergrad and grad school I made friends, and eventually moved to Montreal during the pandemic. Being in Philly and NYC gave me amazing access to art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Barnes Foundation, the Met, MoMA and all the galleries—that experience deeply influenced my gaze.

h: You grew up in a Catholic environment. Has your relationship to Catholicism evolved into something more complex than belief or rejection? Does it still act as a kind of creative friction: something to resist or reinterpret?

GP: Growing up in a Catholic family distorted my brain for sure. To stay sane, I had to be naughty behind everyone’s back, whether that meant being rebellious with my friends or drawing taboo subjects. It felt like creating a secret room underground, one that no one else could know about. Creating the subtext of these ambiguous narratives—as I do in my work—could be coming from this sense of burrowing into secret internal spaces or realms, which are hidden under the surface or within the details of everyday life. But growing up, learning art history from the Baroque and Renaissance periods was fun. Back then, everyone had to make art based on religion, but there are layers you can enter to understand these artists, and I felt connected to them.

h: Your work moves in a suspended, almost dreamlike temporality, as if moments stretch and melt instead of unfolding linearly. What does time mean to you on the canvas?

GP: I like to think about time as moving in circles that never touch, like a spiral… like variations of experiences or similar moments that recur over and over in different configurations. For me, time connects us with the earth, the sun, the moon, our bodies, the weather, and the seasons. These are all distinct experiences of time. Then, there is memory, which has its own sense of time. For me, time and space relate to memories and fantasies, dreams and imaginations, images and narratives. I like to play with all of this, more instinctually than in a deliberate or cerebral way. It’s an abstract practice, as the canvas has strangely simple dimensions, yet it’s a space where I can play with multidimensionality through painting.