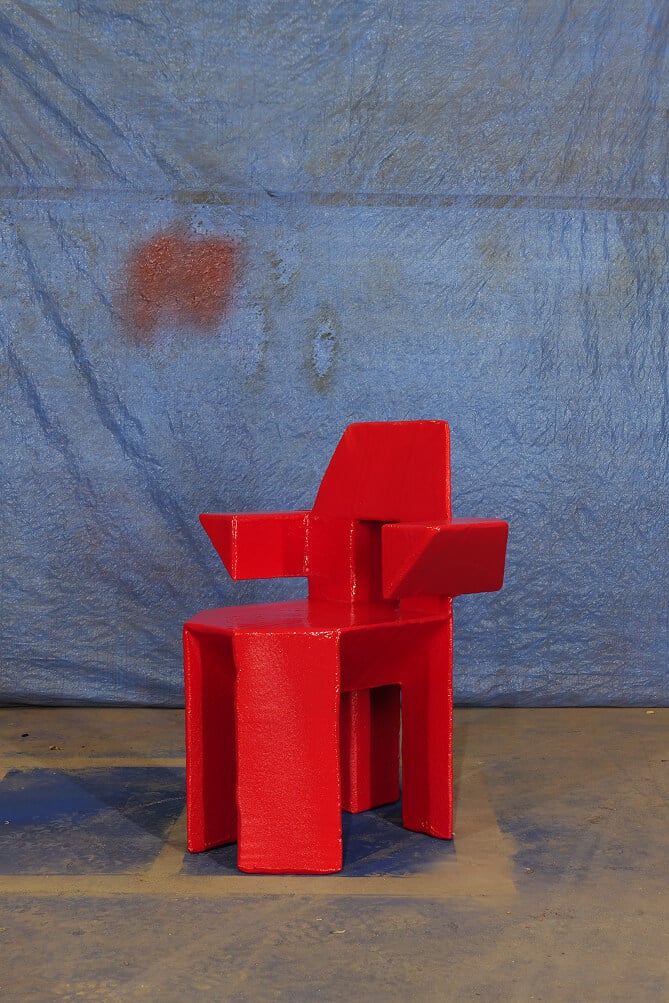

50 Armchairs

Courtesy of MAX LAMB

Jeanne Greenberg Rohatyn was born into the art world, her childhood framed by Warhols and Judds, her worldview shaped by brushstrokes of experimentation and vision. Today, she continues to sculpt that world on her own terms. With her Upper East Side space on New York’s Museum Mile, Greenberg Rohatyn has created a hybrid: part art gallery, part high design showroom, entirely embedded in contemporary culture. Housed in a historic building originally designed by architect Ogden Codman—with a past steeped in art residencies and studio life—gallery Salon 94 now represents the furniture of both the Donald Judd and Gaetano Pesce Estates, honouring a legacy of radical thought passed down through generations. In this conversation, we speak with Jeanne Greenberg Rohatyn about collaborating with artists like Urs Fischer and Tom Sachs, and what it means to run a gallery today—when the role of the art space is being questioned, reinvented, and reimagined.

hube: Salon 94 is a studio that’s been reimagined as a gallery and domestic space. How does this unique setting influence visitors’ interaction with the artwork? Do you think the intimate atmosphere encourages a deeper, more personal connection to the pieces, or is there a risk that it limits how people perceive the art?

Jeanne Greenberg Rohatyn: Salon94 is a domestic space, but bettered and exaggerated—it’s architected to enhance looking. It was originally built to show and make art, not to be lived in, so it had perfect bones for an art gallery. The space was built to enhance art though it throws a curve ball for the artists who show there. The white cube model eliminates distractions, allowing for a neutral playing field and a fixed experience—this is not my approach or intention. In contrast, our gallery adds layers of complexity through architecture, design, and objects—even flowers or scent. Perhaps this creates initial challenges, yet each artist would agree that this magnifies their narratives in a remarkable way, creating true ‘aha’ moments. The natural light moving through Salon94 also changes the experience—visitors see things differently throughout the day. Our second floor offers a version of a white box room, with a curved ceiling and corners like an infinity room. It a piece of the future in the midst of the past.

h: Having grown up surrounded by such iconic works and figures—your father Ronald K. Greenberg, a prominent contemporary art dealer, brought home pieces by Andy Warhol and Donald Judd. How does your own upbringing in the art world shape how you engage with your own children and expose them to art in ways that go beyond just ownership?

JGR: I’m very lucky because the art business is a family business. I’ve had regular dialogue with my father for many years, working with him, and now my sister in the gallery. Now I also have three children who are adults themselves. They are interested in the art—they’ve grown up around it, and they’re each interacting with it in their own way. My middle daughter is people curious, interviewing various artists and creatives for podcasts—she is flexing a different muscle and finding her voice. My muscle is my eye.

h: Is there an artist you’ve been eager to work with or present through Salon 94, but haven’t had the opportunity yet? What draws you to their practice?

JGR: I am at an advantage, in that I have this wonderful space to show art, but at a disadvantage, because I am not a mega-gallery with their stables of artist. I can certainly manifest mounting exhibitions of, say, Jenny Saville or Julie Mehretu, though this might not be realized for many years. Today, we continue to discover new artists, and give different practices a platform. It is also the perfect space to merge art with design, and one of the rare spots in New York that can do this seamlessly.

h: Given the ever-expanding landscape of contemporary art, how do you sift through emerging talent to identify the artists you want to champion?

JGR: We’re always traveling and looking from art fairs, to biennials, to exhibitions by young curators. Our gallery tends not to show emerging artists that often anymore—we realized our sweet spot is an artist who already has an audience but needs to notch it up. Who needs repackaging? Who needs to be given a bigger voice and platform? We’re very good in terms of telling an artist’s story through our installations, photography, and the writers or directors whom we commission for essays or film. Spending the concentrated time to build an exhibition, we make sure that our audience has a special experience when visiting the gallery.