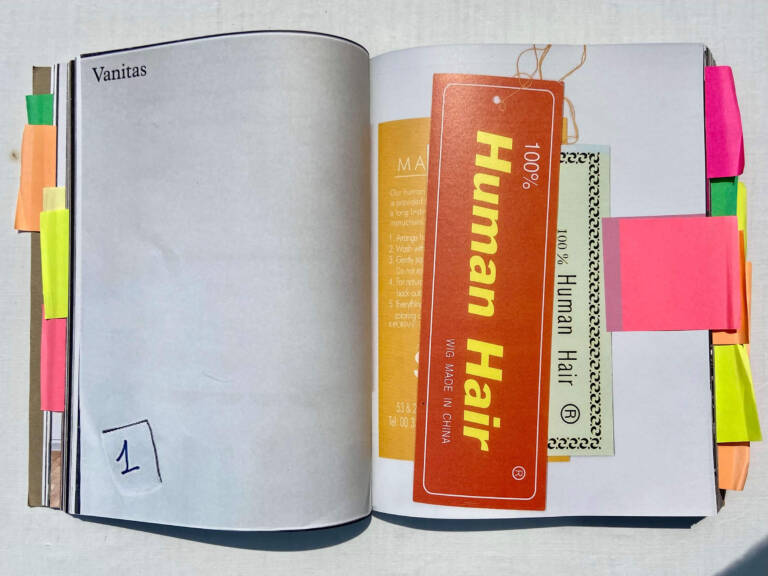

VANITAS II, 2024

Silicone, natural hair

Approximately 30 cm per sphere

Photography by BORIS KIRPOTIN

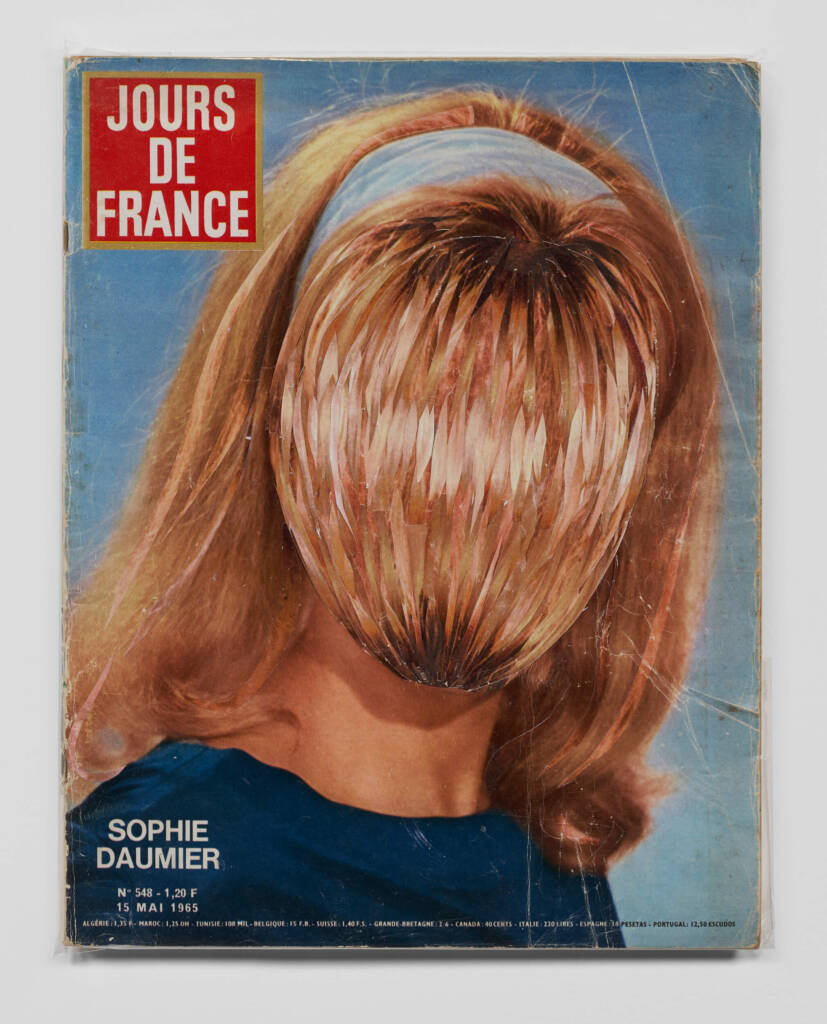

HAIR PORTRAIT, 2015–24

Vintage magazine, plexiglass, polypropylene, Approximately 34 x 26.5 cm

Photography by PETER COX

Martin Margiela is a fashion iconoclast celebrated for a creative vision that eschews ideas of propriety in favour of the radical, conceptual, and subversive. After stepping away from his eponymous label in 2008, he turned his focus to art, where his signature exploration of deconstruction, appropriation, and copy culture has continued with creative abound.

Margiela’s artistic approach resists simple categorization—like his work in fashion, it inhabits a permeable space between mediums and genres. His focus is less on the object than on what is revealed when the object is deconstructed or recontextualized. Through fragmenting and reassembling familiar forms, he explores the tension between the visible and invisible, questioning how each is understood and defined.

Moving into the art world has given Margiela the freedom to expand on ideas once bound to the rhythms of the fashion industry, all while preserving his signature anonymity—his aversion to interviews and industry events, photography and film, persists.

Discover a rare glimpse into Martin Margiela’s artistic world in our interview, where he reflects on the evolution of his creative vision, the intersection of fashion and art, and the enduring power of anonymity.

hube: Artists transcend the material world, entering the realm of symbols, ideas, and myths. Is this the best way to achieve immortality?

Martin Margiela: Achieving immortality is not at all one of my goals; I never think of this matter during the creative process. I love the opposite of eternal—the ephemeral, which is present in performances. For me, experiencing a particular atmosphere is more powerful than looking at any material artwork. As soon as a work is completed, I am excited to imagine its presentation. It is a moment of intense joy because it means it is ready to be shared. Unfortunately, I want to keep every newly finished artwork for myself, so I leave it in my atelier for a certain period to contemplate it as long as needed. Sometimes, enthusiastic reactions from outside help me to send it into the world.

h: Deconstruction, transformation, and moving beyond reason were important ideas in 20th-century art. These are closely linked to the concept of humanism. How do you see the future of humanism?

MM: Deconstruction and transformation have always been very dear to me. I dress mostly in secondhand clothes, so back in 1988, it felt obvious to present transformed secondhand clothes together with new fashion designs in one collection. The idea of giving new life to the discarded touched me, but it was highly unusual in the fashion world back then—sadly almost unacceptable. Today, I am happy to see how secondhand clothes have been ennobled as “vintage.”

In my art, I still love transforming found objects. Some direct results are the DÉODORANT (2021)editions, recycled plastic containers with Nymphenburg porcelain; BODY PART (2019), drawings on projection screens; HAIR PORTRAITS (2015-2022), collages on vintage magazine covers; SCROLLING IMAGE (2021), a series of drawings displayed on billboards; BUS STOP (2020)and PODIUM (2024), urban objects covered in artificial fur; TOPS & BOTTOMS (2023), underwear forms cut from antique plaster casts; SHORE SHOES (2024), washed up flip-flops reworked into new shoe shapes. I give my newly produced catalogues a used feeling by sticking Post-its onto certain pages. I find common objects within daily situations very inspiring. Creating something extraordinary out of the ordinary intrigues me.

As a child, I loved to isolate myself in a world of my own imagination. I remember how disturbing it felt every time I was called back to reality. This was probably when my strength of imagination forged my creativity. It may also be the root of my later desire for anonymity. But it wasn’t until the late 80s, when I was Jean Paul Gaultier’s assistant, that I discovered that becoming famous transformed a person into a public object. I rejected the idea that my privacy would suffer as a consequence of success.

As a kid, I would constantly, almost exclusively, draw portraits and people in full dress. The human body has always been my main inspiration, in all its possible forms. Even when working on empty interiors or bare staircases, I aim to show absence rather than emptiness, which creates the feeling that somebody has just left the scene. I was never, and still am not, a social person. To this day, the need to be on my own is absolutely necessary in creative moments, it’s crucial for the realisation process. When I feel confident about an artwork, I am more than willing to share it with an audience.

How do I see the future of humanism? I am not able to answer this question properly; we live in such an uncertain world today. I strongly believe in humanity. I like to think that human beings will always need human beings.