Orhan Pamuk is a literary force whose work explores the complexities of identity, culture, and history, offering a nuanced perspective on the intersection of East and West. As the winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature, his writing has reached far beyond Turkey, offering readers insights into the soul of his homeland. His novels—Snow, My Name Is Red, and The Museum of Innocence—are not just stories, but explorations of the ways in which time, memory, and love shape the urban fabric of Istanbul.

Through his evocative storytelling, Pamuk presents Istanbul as an entity that is as vivid and complex as any of his characters. Just a month after our conversation, I found myself walking the city’s streets and felt its timeless beauty and the pulse of its contradictions—just as his books had promised.

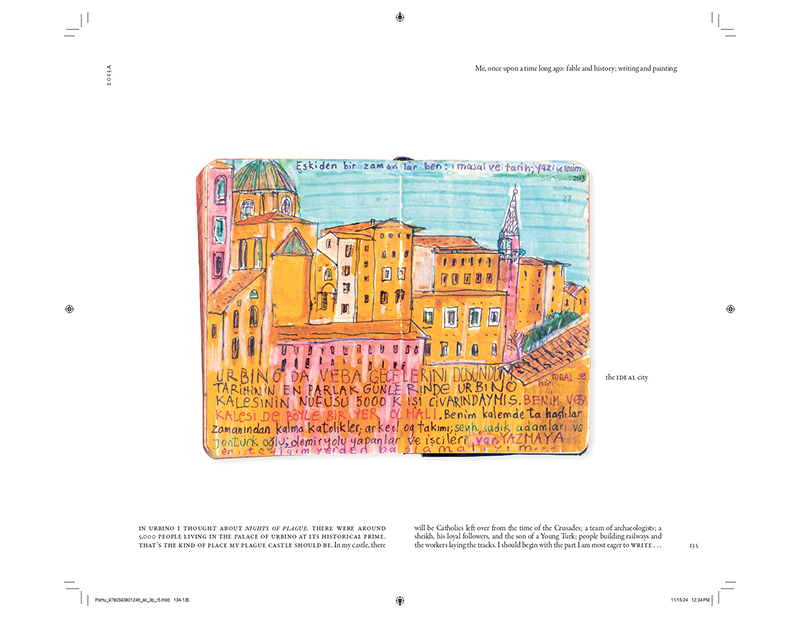

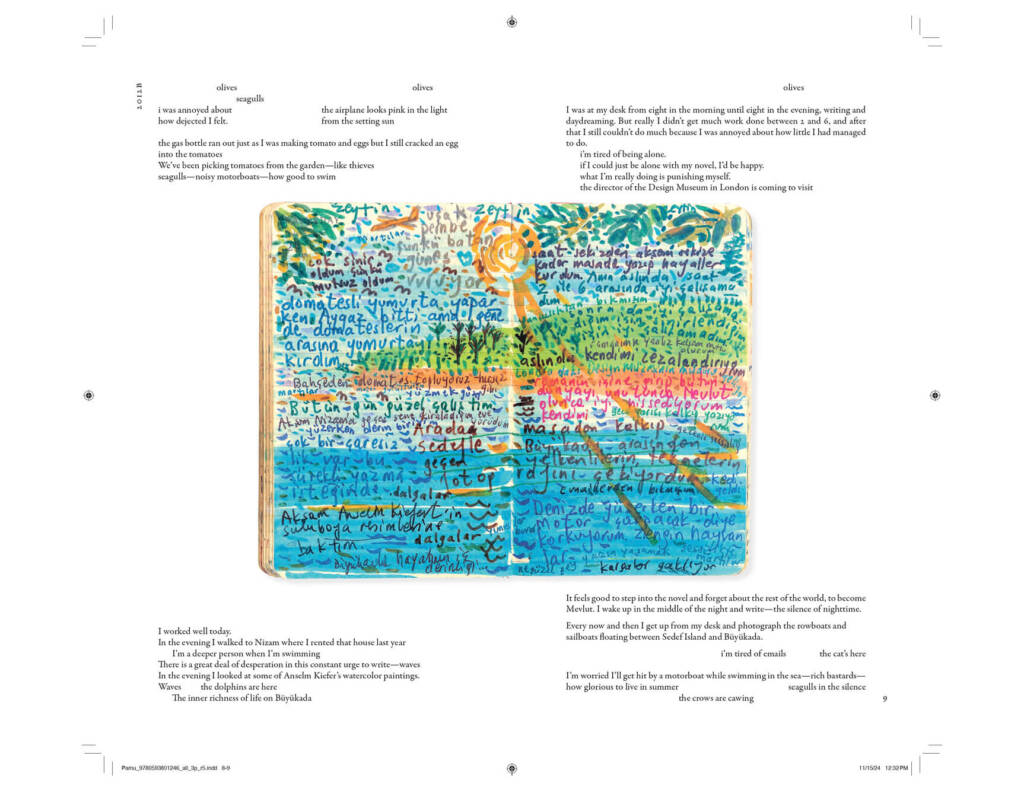

We spoke with Pamuk ahead of the release of his latest novel, Memories of Distant Mountains. Accompanying our interview are sketches from his beloved Moleskine notebooks, where he has been capturing the world for the past 16 years. Once aspiring to be a painter, Pamuk stepped away from art for reasons he “still can’t explain.” These small, intimate canvases reflect a passion for painting that Pamuk has quietly sustained alongside his writing over the past 16 years.

Sasha Kovaleva

hube: A hero’s literary life can fit within a single novel or a single page. Does the novel liberate characters from the pain of everyday reality? Are readers seeking the same thing?

Orhan Pamuk: No, not at all. Novels present everyday reality, but in an edited form—readers look to characters to see something meaningful in the familiar pain of daily life. We shape reality to suggest meaning, though we don’t actually escape from it.

There are two approaches to literature: one seeks to capture the world by reducing it, telling stories that distill life down to dramatic moments, almost like Borges’ map, which covers the world completely, as vast as the world itself. This is the epic approach. The other is the dramatic approach, focusing on smaller, more immediate experiences. A novelist, I believe, should hold both perspectives.

The joy of writing isn’t in escaping the “boring” surfaces of reality but in reworking them, creating new surfaces that suggest deeper layers beneath. Unlike the epics of the past, filled with battles and grand adventures, modernity has given us a desire to examine the surfaces of ordinary life and find unique tastes, styles, and qualities in them. The goal of literature and art, for me, isn’t to flee from these surfaces, but to reveal a new meaning, a new structure—a creation that resonates with the pattern of life.

h: When you create your characters and assign them roles, you imbue them with purpose. Do you believe that everyone has a purpose in life?

OP: We all have purposes, but we’re rarely fully aware of them. In The Red and the Black, Julien Sorel has one clear, perhaps shallow, purpose: to rise in the social hierarchy. The reader, the character, and even the author all know this. He’s intelligent, good-looking, and cunning, but what keeps us reading isn’t this obvious goal. It’s the style of his ambition—the details of his social manoeuvres, his love affairs, his cynicism, his lies, his devotion, and his romantic entanglements.

Novels shouldn’t focus on grand purposes or sweeping narratives. In fact, they’re often best when they embrace purposelessness. Our lives may seem superficial, yet novels lend them a meaning and purpose. A life without conscious purpose isn’t meaningless. A powerful political novel, for instance, doesn’t need to amplify its characters’ political goals. Instead, it reveals that the texture of these characters’ lives diverges from their politics. The drama lies in the tension between a character’s purpose and the texture of their life. This difference—this contradiction—between personal and political goals shows us the true essence of the novel.

I’m not writing novels to glorify political heroes or villains. My aim isn’t to propagate ideas about good and bad. I write novels to reveal the intricate texture of life, where grand purposes clash with the simple, detailed fabric of daily existence.