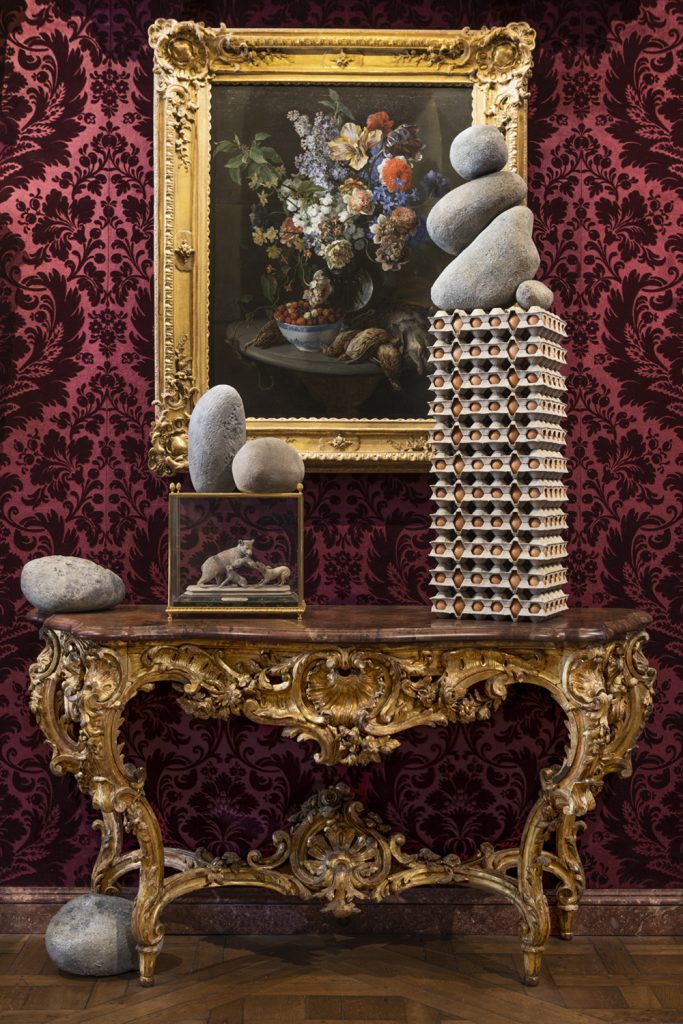

Every stone should cry exhibition view, 2019

Every stone should cry, 2019

Théo Mercier is a French sculptor and stage director whose artistic prowess unveils harmonic contradictions of sculpture. Mercier’s work is a testament to his commitment to freedom, challenging the mechanisms of history, objects, and representations. As a resident at Villa Medici, a Marcel-Duchamp prize nominee, and a Silver Lion recipient at the 2019 Venice Biennale, Mercier’s journey explores the topics of anthropology, geopolitics, and beyond. Each piece becomes a narrative that dismantles conventional notions and invites viewers to contemplate the nuanced intersections of art, culture, and the world by dismantling the concepts of time and space.

hube: Could you tell us about the influence of your personal background and cultural experiences on your artistic practice? How do these elements shape your perspective and the stories you choose to tell through your art?

Théo Mercier: I didn’t study fine arts. For some years, I went to a School of Design in Paris and in Berlin. I’ve always been very interested in how things are made, and I must admit that I draw more inspiration from industrial, daily life objects and crafts such as carpets, ceramics, or shampoo bottles than from art itself. I always wonder why things are made in a more practical and conceptual way. For me, objects are not only about material and fabrication but there is also an economic and political aspect to reveal. In my work, objects are most often the pretext for talking about humanity and our relationship to one another.

h: Your work often combines various mediums, from sculpture to performance art. How do you choose the medium for a particular concept, and how do these diverse forms of expression contribute to your artistic vision?

TM: I’d like to see my work as an answer. Whether it’s an exhibition or a performance, my ideas are usually ‘reactions’ to something, to a space, an audience, an economy, or a way of producing. I always look for the most appropriate medium to answer some kind of muted question. It’s like imagining what would be the most relevant language to speak in. I’m free to use the medium and the materials that feel the most appropriate, and it often depends on the space and context. It could be an entire mono-material environment such as sand sculpture, a composition made out of some antique sculptures that were stored in the basement of a Museum for years, or an installation made out of recycled waste… In fact, it is a very sensual and intuitive way of choosing the medium.

h: You once mentioned that you listen to the space. Can you elaborate on this, how exactly does it happen?

TM: I don’t really know… I guess this is the magic of being an artist! This is just the thing I’m good at. I often say that I’m not inventing anything; everything already exists, and my job is to bring out the ghost of space because most of the time it’s the space that’s telling me what to do. So I need to take time to observe it and to listen to it.

I’m asking myself — what is the sound of this space, who’s coming forward, and who’s that guy that looks like a security guard? For me, it is essential to understand the space as if it was a piece of territory. I wonder: what is the temperature, what is the quality of light? When people enter space, are they speaking loudly, or do their voices go quiet? All these little clues help me to imagine what’s the most appropriate thing to do.

And there is a radical difference between doing this job within institutions where three people visit per day, or in institutions where 4000 people visit per day. Sometimes, people are coming for my show; and sometimes, they are coming because it’s a patrimonial monument. So, I always do different types of work for these spaces. When I say that I’m listening to the space, to what the architecture really is, I also think of how it’s feeding these people, almost as if it was an organism. I visualize it as a big animal with humans inside, and I think of how the humans are moving there and what type of humans they are… These are all the things I have in my mind when I look at a space.

Strangely, my ideas come with visions. And for that to happen, I need to spend time sitting and walking in the space where I will present works. And suddenly things happen, I have some visions or words in my mind, I take notes and do some rough drawings. I feel a little like a detective asking the space what the enigma is, what I will have to resolve this time…