Lines. Fabric. Form. For designer Steve O. Smith, these elements converge to create garments that are as much art as they are fashion. With a background in fine art and a passion for drawing, Smith has developed a unique approach that transforms his sketches into dynamic silhouettes, challenging traditional boundaries and redefining wearable art. In this interview, he delves into his creative process, the challenges of bringing two-dimensional drawings to life, and the inspirations that fuel his innovative designs.

hube: Your work beautifully blurs the line between fine art and fashion. Can you share how your background in fine art influences your design process? What do you consider the biggest challenge in transforming a two-dimensional sketch into a three-dimensional garment?

Steve O Smith: I did my BA at the Rhode Island School of Design, and most of my friends were in fine art – so I was around that a lot. I think that’s definitely influenced the direction I ended up going. I’ve always had a very drawing‐based approach to design. The challenge? It’s blowing that drawing up to scale. It’s easy to fall into the trap of just exactly replicating what you do on paper when you’re working in real life.

But it’s important to remember that it’s a totally different drawing – just like if you painted from a sketch, you use it as an influence for the spaces and what you’re trying to portray, but there’s room for interpretation. I try not to be too dogmatic about doing the same drawing I did on paper. I let the garment develop as its entity, even though it’s influenced by that two-dimensional work.

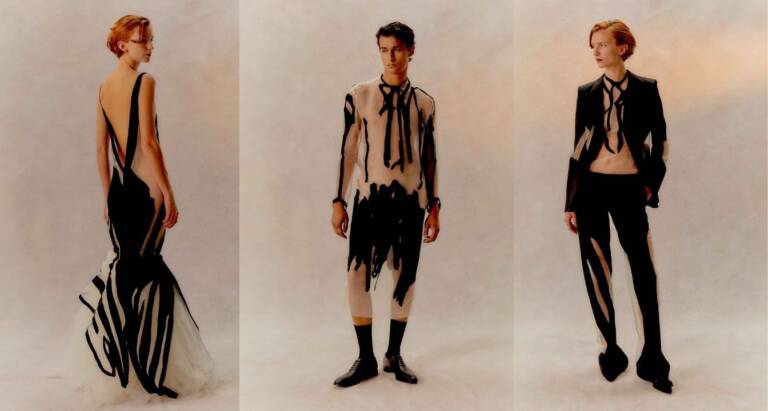

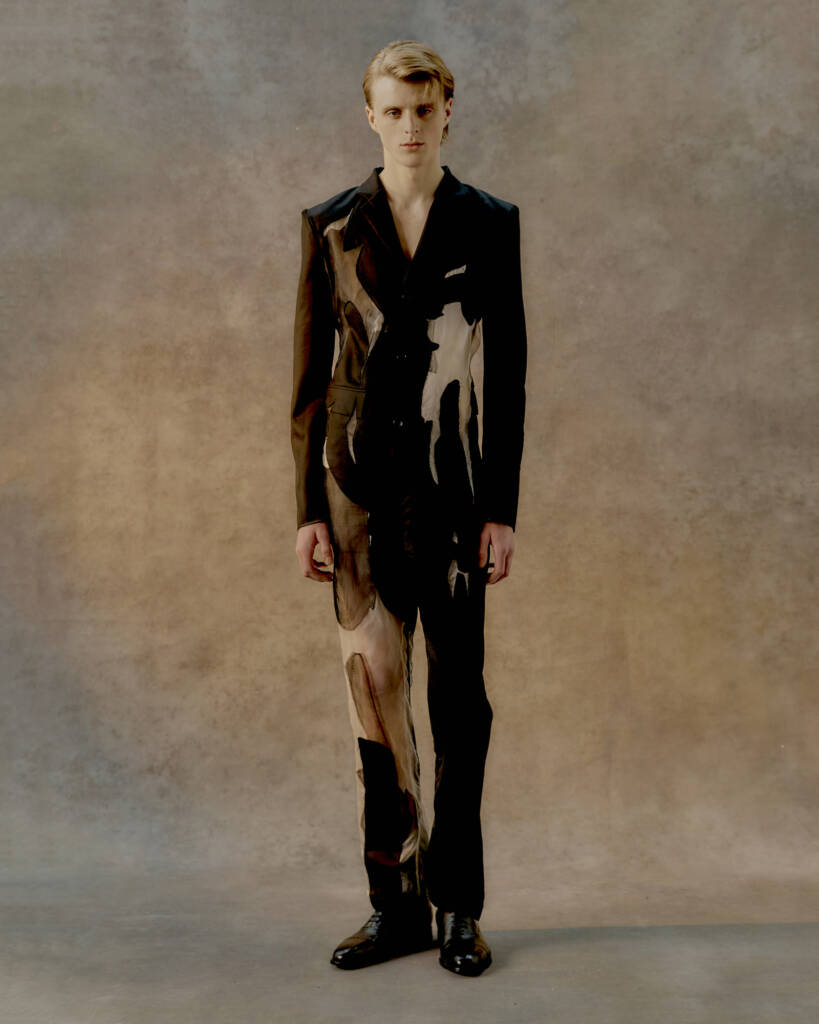

h: Your AW2024 collection is described as ‘a life-size drawing in the round’. How do you maintain the spontaneity of your sketches throughout the pattern-cutting and construction processes? Are there any particular techniques you’ve developed to preserve that artistic essence?

SOS: Well, it’s interesting because I’ve mostly been working with graphite sticks and pencils for the last year and a half. The techniques I use involve appliquéd silk crepe on organza. It creates these extremely dry, drawing-like pieces – there’s no wet medium involved. But when you scale those up, they end up with this sort of inky feel. Lately, I’ve started drawing in ink, and I’m really curious to see how that will change my techniques. I’m musing on it a bit, but basically, it all comes down to finding that balance between the precision of the drawing and letting the fabric evolve its own character.

h: How do you maintain the spontaneous energy of your sketches during pattern cutting, given that transferring a sketch to a full-size garment is such a demanding task? Is there a secret to preserving that creative spark?

SOS: Oh, definitely. There’s a way of pattern cutting that keeps the spontaneity alive. When I was at St. Martin’s, I had this amazing pattern tutor, Mark Talbot – he was actually Westwood’s first pattern cutter back in the ’70s. He was super strict, very charismatic (and a bit intimidating), but he’d always come up to me and say, ‘You need to cut these patterns like you draw’. It took me a while to really get what he meant, but I even printed an email he sent me and stuck it on my fridge that summer – the summer I started cutting like I drew. After ten years of pattern cutting, it’s become second nature. It’s all about seeing the pattern pieces as drawings, keeping the proportions and expressiveness intact. Draping is naturally expressive too – the final gown from our SS25 collection was draped directly onto the form, bypassing traditional patterns entirely. The secret is to trust your eye, cut like you draw, and don’t get bogged down by math.