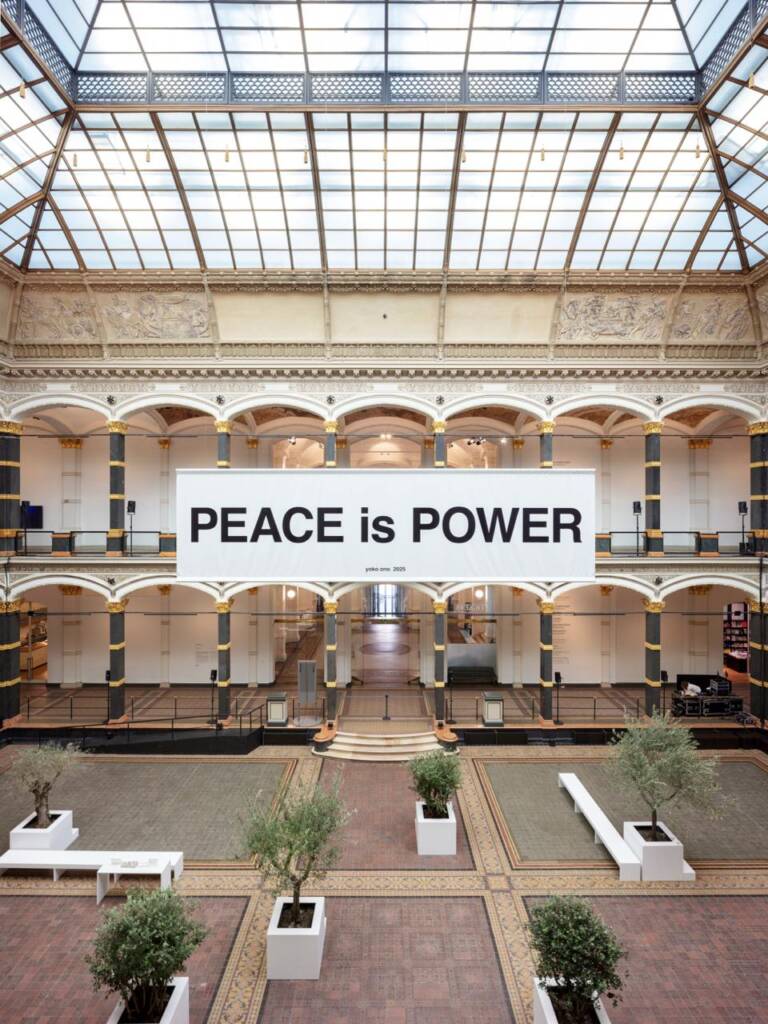

Wish Tree for Berlin, 1996/2025

YOKO ONO: MUSIC OF THE MIND installation view at GROPIUS BAU, 2025

Photography by LUCA GIRARDINI (GROPIUS BAU)

Photography by LUCA GIRARDINI (Courtesy of GROPIUS BAU)

Questions. Provocations. Possibilities. For curator Patrizia Dander, these elements converge to dismantle outdated museum norms and create radical art experiences – like she did with the bold spirit of YOKO ONO: MUSIC OF THE MIND exhibition, which opened on April 10, 2025, at Gropius Bau. Here, over 200 works spanning seven decades are brought together, inviting visitors to discover, re-experience, and, in some cases, even complete the works themselves. In this conversation, Dander reveals how her vision and curatorial approach have been transforming institutions in Düsseldorf and Munich, and now Berlin, challenging us all to rethink what a museum can – and should – be.

hube: Throughout your career – from co-running the white light exhibition space in Düsseldorf to curating at Haus der Kunst and Museum Brandhorst in Munich – what common thread connects these diverse projects, and how have they shaped your current work?

Patrizia Dander: I’d say the common thread is curiosity. I didn’t start out in the arts – my background is in psychology. But contemporary art pulled me in because it felt like a space where so many aspects of life are negotiated. Art can be weird, beautiful, even disorienting – and that’s what I love about it. I’ve always believed that no one should need a specific background to engage with art. Whether you come from psychology, architecture, or something completely different, there should always be an open door. That’s something I think about a lot when I curate – how to create space for different ways of engaging with art.

h: With your background in psychology, how do insights into human behavior and perception inform the design of immersive exhibition experiences that resonate with a wide audience?

PD: Not in a direct, ‘here’s my psychology toolkit’ kind of way. I finished that degree back in 2002, and I’ve worked in the arts for far longer than I ever did in psychology. But what’s stayed with me is a deep interest in people – especially artists. Through their work, artists offer us new ways of seeing the world – and I love that. So maybe that’s the connection: a fascination with how people think, feel, and make sense of things.

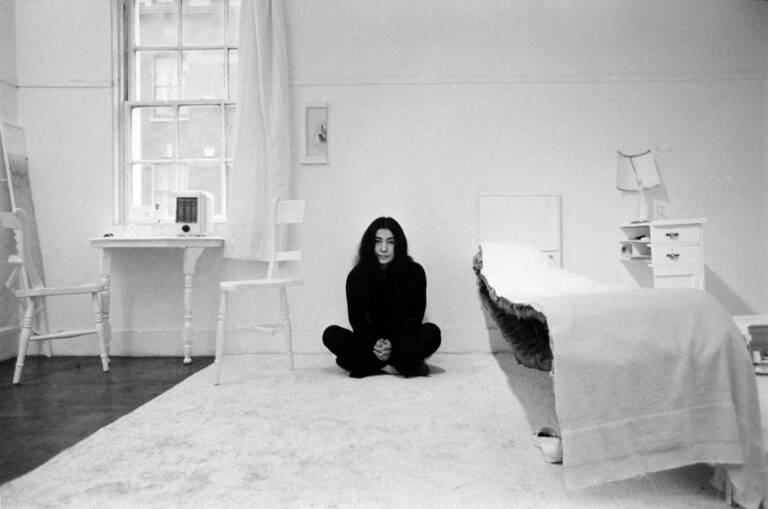

h: Your recent co-curation of YOKO ONO: MUSIC OF THE MIND brings together over 200 works spanning seven decades. How has working with Ono’s radically participatory art influenced your overall curatorial vision?

PD: I first encountered Yoko Ono’s work in the early 2000s at a small exhibition at nGbK in Berlin, and I was completely taken by its simplicity and depth. There’s a real generosity in her work – an open invitation to take part in it, rather than just observe. That always resonated with me. So when the opportunity came to work on this exhibition, it felt like many long-standing thoughts I have had about participation, accessibility, and art finally came together.

h: Yoko Ono’s art invites direct audience participation. What were some of the most unexpected challenges you encountered when adapting these interactive elements for a major institution?

PD: It’s certainly not like curating a conventional painting exhibition. Participatory works require a different kind of caretaking – you have to make space for change. One piece we’re showing, Add Colour (Refugee Boat), has its roots in Ono’s early conceptual paintings. In 2016, for an exhibition in Greece, she developed its current form in response to reports of hundreds of thousands of displaced people arriving in Europe. It features a white boat in an all-white space. Visitors are invited to write messages on the walls and on the boat itself – the work is in constant transformation. That’s what makes Yoko Ono’s art so powerful: you can never predict what it will become.