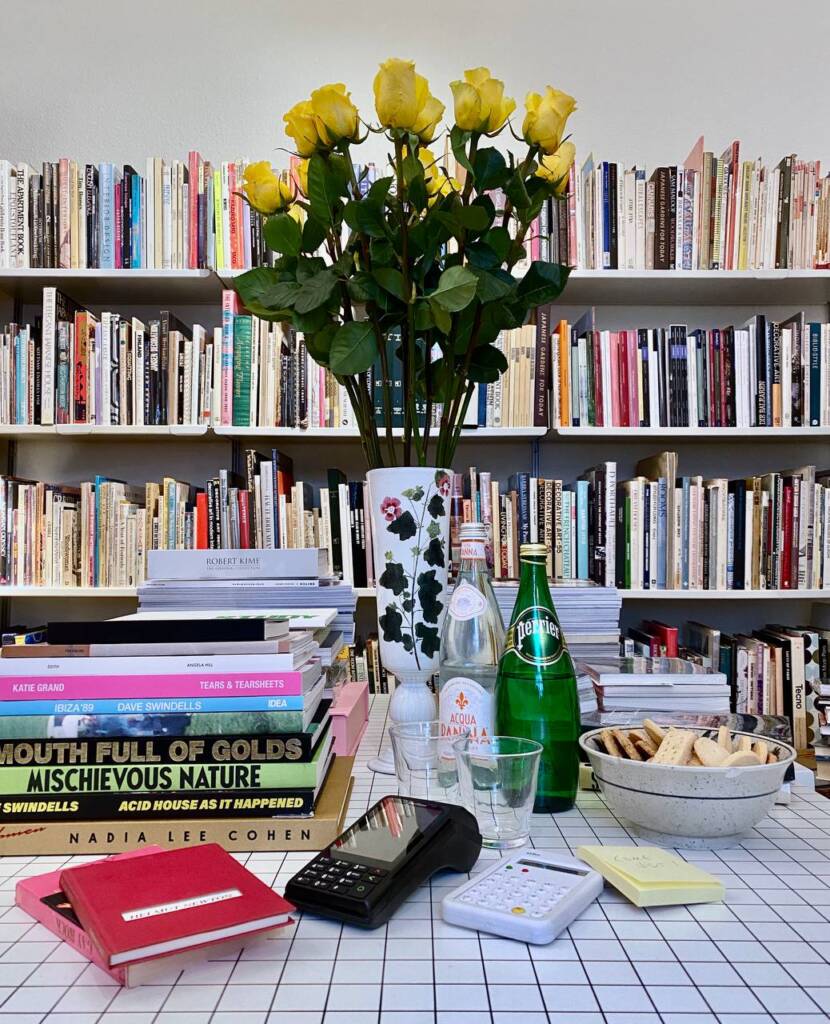

Angela Hill’s IDEA Books is tucked upstairs in Soho, shelving a hidden collection of rare and vintage publications. From the street, it could pass as just another flat, but two flights up, the space opens like a mirage: a gallery disguised as a bookstore, or maybe the other way around. On rotation: rare monographs, bootleg zines, and a hyperreal wax figure of Martin Parr holding vigil by the vinyl. If you’re lucky, Hill is there too—offering tea, straightening prints, pointing toward something buried in the stacks. She’s the A in IDEA, the quiet current running through the shop, but before books, there were photographs.

Hill spent ten years documenting Sylvia, a muse discovered through a chance tip from her husband, who encountered her at the dentist. Lately, she’s turned the lens on Edith, her daughter, bringing the same attentiveness to light, stillness, and time. Angela’s eye isn’t fixed—it drifts between publishing, archiving, and collecting, but always with the same sense of care. In this conversation, we talk to Hill about patience, practice, and what it means to live with the things you keep.

hube: How did books first enter the frame for you?

Angela Hill: I have been reading since I was three or four years old. The earliest thing I remember was little picture books given out at the dentist—they were to teach children how to brush their teeth. I was always surrounded by books as a child and I still have my childhood books now.

h: Do you think the landscape of book collecting and publishing has changed since you started?

AH: Not really, if you want to buy a book you will; there have always been other ways to read and if you prefer those (computers, phones, kindle, listening books) then you won’t buy the books.

h: Bookshops like Reference Point in London, OFR in Paris, and Climax are also carving out strong voices in the scene.

AH: OFR certainly have been there forever and we were buying from them from the 90s before we had a store.

h: How did opening the Soho shop shift the way people engage with your work? Did having a physical space change the energy of the project?

AH: Yes, it did, in a good way. Once they find us and come in, they already think they have achieved something! The front door is quite anonymous and then you have to come up to the second floor. I think IDEA is appreciated for being a bit of a hidden cache and people are genuinely pleased to have made the effort, and then they tell their friends. So many now are regulars who are very good friends.

h: You move between collecting and publishing with ease—how do those two rhythms inform each other? Do they ever clash?

AH: No, they do not clash. They totally complement each other. If we publish a book by one artist who has produced other books previously, we make sure we carry all of them. We collect the catalogues, rare out of print books, and any ephemera relating to them so that we can present a spectrum of work.