Sougwen Chung is a New York–London based artist, researcher, and founder of Scilicet, a studio exploring the evolving relationship between humans and intelligent systems. Their practice centers on human–machine interaction across drawing, performance, and robotics. Chung considers artificial intelligence not as a tool but as a collaborator—an evolving partner in gesture, memory, and meditation. Their ongoing project, Drawing Operations Unit: Generation (2015–), translates biosignals and neural data into shared acts of mark-making between human and machine, questioning authorship and presence in the digital age. Chung’s work has brought them international acclaim, having been exhibited at the Victoria & Albert Museum, Haus der Kunst, Art Basel, and The Drawing Center, and collected by major institutions including the V&A—the first to acquire an AI-model. A former research fellow at MIT Media Lab and Bell Labs, Chung was recently honoured with the TIME100 Impact Award and named among TIME’s 100 Most Influential People in AI.

h: How did your practice start? What made you develop that first Drawing Operations system ten years ago?

Sougwen Chung: I consider myself a life-long practitioner—beginning with instruments and computers at a young age. The practice has turned into a devotion to drawing in all its forms—as performance, as movement data, and as an ecological, relational medium. These ideas were first rooted in the pursuit of the beauty of a non-human gesture, in my project Drawing Operations, when I was a research fellow at the Media Lab at MIT in Boston. We recently celebrated our 10-year retrospective in Germany: our artistic research of embodied collaboration.

h: How would you describe your creative relationship with D.O.U.G.?

SC: D.O.U.G. is an acronym for Drawing Operations Unit: Generations—indirectly borrowing from the acronymic nomenclature of projects like AARON by Harold Cohen. I think of my creative relationship with D.O.U.G. as an embodied collaboration—a co-aesthetic system in which human, machine, and environment are charged with generating open choreographies of sensing and meaning. For me, the collaborative premise is one of making with, becoming with, in a state of relation rather than reduction. Perhaps more simply put, collaboration is a relationship rooted in change and the awareness that our relationships with technology, our environments, and our sense of our own bodies are there to be shaped, and that we have agency over them. My work serves as a durational laboratory for investigating these relational modes through research on emerging technologies and bioscience, as well as critical theory and the philosophy of technology, and knowledge practices like qi gong and Vedic meditation.

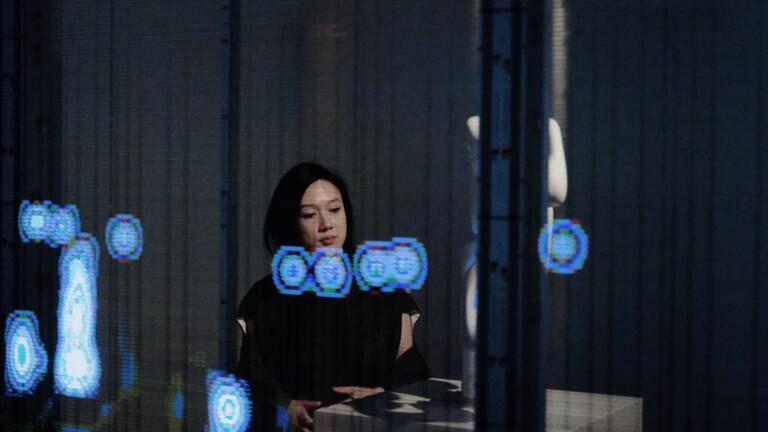

Ecologies of Becoming, 2025

Courtesy of SOUGWEN CHUNG

Ecologies of Becoming, 2025

Courtesy of SOUGWEN CHUNG