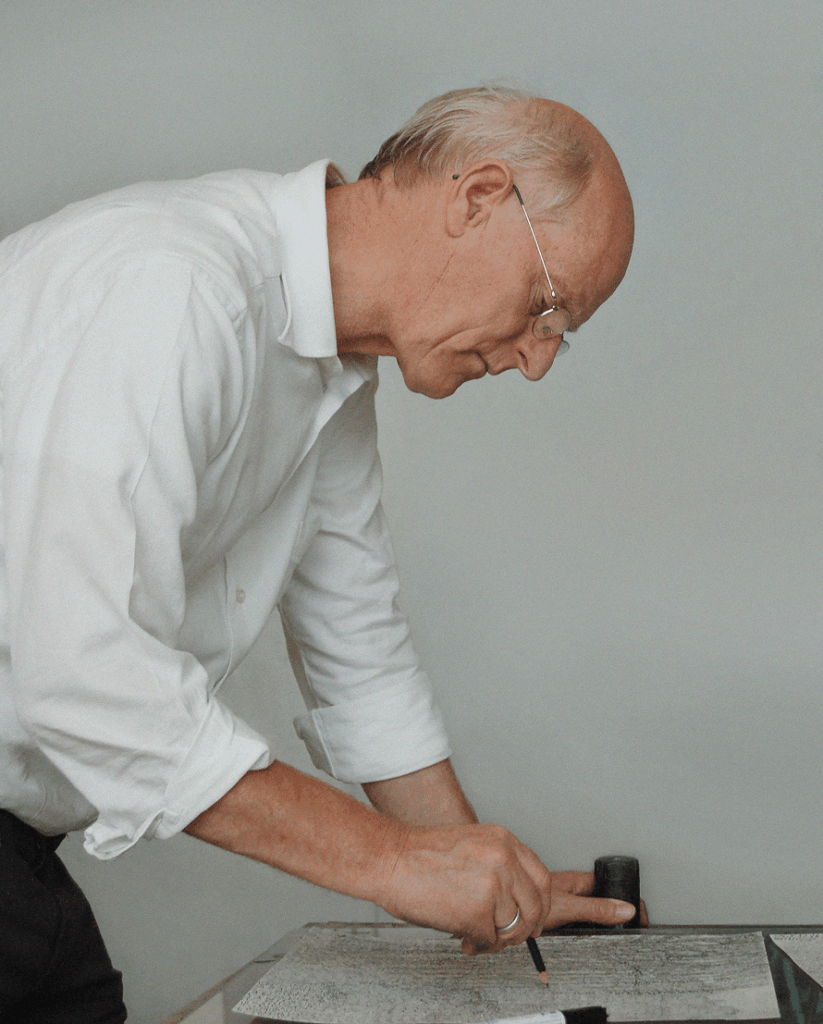

Photography by DAVID KALUZA, 2007

Courtesy the Artist and LISSON GALLERY

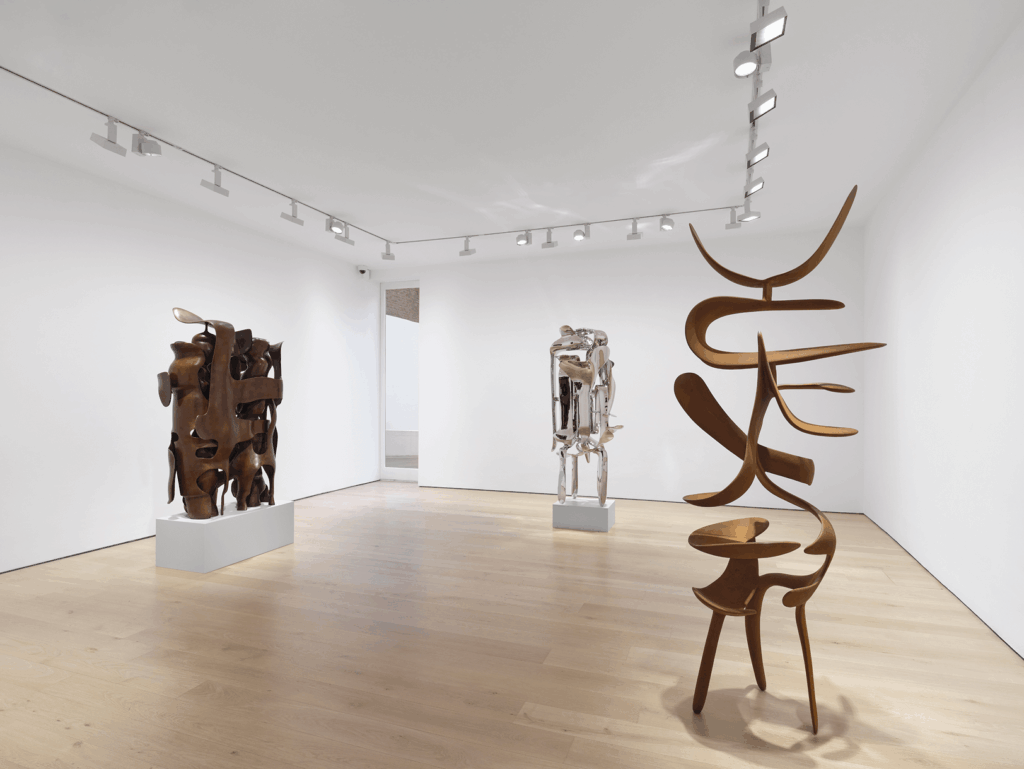

Incident (Vertical), 2022; Corten Steel; 230 x 84 x 94 cm; 90 1/2 x 33 1/8 x 37 in

© TONY CRAGG, Courtesy of LISSON GALLERY

Photography by MICHAEL RICHTER

Incident, 2023; Stainless steel; 185 x 84 x 87 cm; 72 7/8 x 33 1/8 x 34 1/4 in

© TONY CRAGG, Courtesy of LISSON GALLERY

© TONY CRAGG, Courtesy of LISSON GALLERY

1988 Turner prize winner Tony Cragg is a widely recognised name in the field of contemporary sculpture. Nearly 4 decades on, his love for the medium still resonates with each sentence he speaks. Although Cragg has largely remained private, the source of his deeply intuitive practice is clear: a profound reverence for nature. A naturalist in his own right, the evolution of his sculptures often mirrors the forms he observes on his morning walks through the forest. By 1981, Cragg had already participated in twelve exhibitions; today, his work continues to be shown across galleries and museums worldwide.

While Cragg’s work is appears almost idyllic, appearing to take on a life of its own, it is never purely spontaneous. Each piece is a response, rather than an impulsive creation. Moving like water droplets down a windowpane, his forms bend and fold, using materiality to create a dialogue between the outer world and the artist’s mind. As American naturalist Tom Brown Jr. writes, “this earth is a garden, this life a banquet,” Cragg’s work continuously captures the richness of textures, shapes, and delights all around, resisting any flattening of their complexity.

In this interview with hube, Cragg discusses walking away from Fluxus, listening to Jimi Hendrix in the studio, and whether materials might have a mind of their own.

hube: Sorry if I’m sounding a bit raspy, I’ve lost my voice.

Tony Cragg: It’s the Christmas carols and alcohol that does it [laughs].

h: So going back, when you look back at the earliest days of your practice, what do you feel has changed the most in the way that you approach work and move within your practice?

TC: You mean from 55 years ago to now?

h: Yeah.

TC: How much time do we have? So many things have changed. First of all, when I started, it was just a pure delight of making things. I had no technical abilities and didn’t know anything about sculpture. But in Britain, in ‘69, ‘70, there was Henry Moore in one generation and Anthony Caro in another. There was awareness of Richard Long and Gilbert and George. Being a young 20-year-old person at that time, I was influenced by what was going on in the art world: pop art and Arte Povera.

There were a lot of movements that centered on finding objects and bringing them into the context of art, like Andy Warhol’s Soup Cans and Joseph Beuys’s Pictures to a Dead Hare. Most of the art making was based on the ready-made principle. This was a very important thing for me to get to start with because I was just looking at the world and the different materials, forms, and shapes in it.

This provided me with an enormous vocabulary of objects and forms, which was what drove my work. But, by the ‘70s, other younger sculptors and myself felt that this ready-made principle was running out of steam — it got to the point where there were BMWs in a museum. And so, I started to carve and move materials around. The very first thing I did was a terrible sculpture. I took some found objects, and made their shadows. After, I took the found objects themselves away. It was just a black mess, but it was the beginning of making things physically for me.

h: Now you can see the way that you experiment with physicality across all of your body work. In your new exhibition at Lisson Gallery, your works unfurl in vertical gesture. What discoveries emerged for you during their making, and even after decades of exploring materials, do they still teach you something new?

TC: Of course. That’s the delight of the thing. I’m not a designer, and I’m not a sculptor that makes something that already exists in another material, so I don’t have a prescribed destination for my work. When I put pencil to paper, I watch where it’s going, respond accordingly, and see what feelings arise.

As with my new work, I was surprised about how it turned out, as I didn’t know what I was going to do. I don’t think good ideas are very good. They’re not helpful in making interesting things, so I end up following the material and my chain of thoughts while working.

h: Do the materials you work with carry different temperaments for you? Do they have personalities, almost like characters?

TC: I would argue they have qualities, but not personalities. Material on its own is just matter; the response comes entirely from the human mind. Objects can exist without ever being seen, but without perception they hold no meaning. It’s up to the sculptor, the musician, the writer, to give the material their personalities and meanings.

h: Where does nature’s tension find its way into your work? Are there elements of the natural world that still stop you in your tracks?

TC: Being alive is what amazes me, to be honest. I am in awe about having an existence. I’ve actually just come out of the forest, as I’ve been walking through it this morning. It’s a cold and windy, very typical autumn day, but it’s somehow just magnificent.

I’m not a religious person in the formal sense, but I am reverent about being alive. I’m astonished all the time. There’s very rarely an instant where I’m not in a state of wonderment.

h: I was looking through your archive, and the drawings in it are so delicate and beautiful. How often do you find yourself drawing today, and does that act still function as an origin point for your three-dimensional work?

TC: Many artists get to a point where they feel that their work just has to be made — there’s not even a conscious moment about it. For me, drawing is more or less like that. First of all, it’s a pleasure to draw, especially if I don’t have to make something specific, but it is also a good way to two-dimensionally short-cut something that would take ages to work out with real material.

Some of my drawings are just explanatory diagrams, and act as instructions or reminders. I also think life drawing, which I did as a student, was invaluable. It’s not just about drawing somebody, it’s about looking at something so subtle, trying to get the feelings and the forms out of it. It doesn’t matter how the drawing works out sometimes.

© TONY CRAGG, Courtesy of LISSON GALLERY

Path, 2025; Corten steel; 236 x 151 x 106 cm; 92 7/8 x 59 1/2 x 41 3/4 in

© TONY CRAGG, Courtesy of LISSON GALLERY. Photography by MICHAEL RICHTER

Contradiction, 2024; Bronze; 340 x 117 x 131 cm; 133 7/8 x 46 1/8 x 51 5/8 in

© TONY CRAGG, Courtesy of LISSON GALLERY

© TONY CRAGG, Courtesy of LISSON GALLERY

© TONY CRAGG, Courtesy of LISSON GALLERY

© TONY CRAGG, Courtesy of LISSON GALLERY

© TONY CRAGG, Courtesy of LISSON GALLERY

© TONY CRAGG, Courtesy of LISSON GALLERY

h: Which creatives are subtly shaping the way you approach your work, whether they’re artists, musicians, performers, or writers?

TC: I’m very enthusiastic about sculpture in general. It’s one of the only activities where we use materials without them being utilitarian — you don’t have to sit on it, or drive it. It’s about expanding material into space and seeing if it means anything.

There are lots of sculptors that I’m interested in. My wife’s a painter, and I keep telling her that painting’s just very thin sculpture, because for me, everything is sculptural, even music. It’s still somebody vibrating the air, and then the ears. I also listen to music a lot: I can listen to anything from Bach to Jimi Hendrix. It’s the quality of the music that I found interesting, not the genre. I also read a lot and walk in the forest every day.

h: You’ve placed your work in so many remarkable settings around the world. Is there a moment that felt dreamlike to witness? And after showing work both outdoors and within walls, do you feel more at home in one space than the other?

TC: After the Second World War, we knew that all materials and objects could be subjects of art. When making work indoors, you can create things out of sugar or chocolate. Making things outside is very different, because there’re climate and human concerns. You go into a building of your own volition, whereas a sculpture in a public setting is subject to so many people seeing it involuntarily.

Every time you put a sculpture out there, it’s like you’ve put an alien down in the back garden, and everybody gets a little bit aerated about it. After a while though, they usually say it’s nice, and that it’s their sculpture now. You can’t have it back.

h: Has there ever been an instance where one of your publicly installed works did get damaged?

TC: Strangely enough, nobody’s ever done any damage to my work. That’s quite surprising in some ways.

We did an exhibition recently in a museum in Dusseldorf called Please Touch where visitors could touch all the big works. 135,000 people came for that show in a period of two months. They all touched every single work and we were amazed about how little damage was done. People were very respectful of it.

h: Are there ideas or works that have remained unresolved over time, pieces that resist finality? How do you stay with that uncertainty without losing patience?

TC: I have a little list of work I’m involved in at the moment — there are 34 projects on it, which I’m doing simultaneously. It sounds grand, but it’s simply because I’ve been working on some of them for five or six years, and they don’t seem to be going anywhere. I don’t want to give up on them.

h: Do you feel that the connection between the work and a grander idea or concept is necessary, or it’s more about evoking emotion?

TC: We live on a planet we are impoverishing and destroying. We’ve created a world driven by the simple parameters of industrial production. Its geometries are highly repetitive, and this destroys forests that are full of fantastic forms.

First, we need a meadow, so we take the forest down and plant it with corn. Then, after a while, we need a car park — we’re dumbing things down. But sculpture is about discovering new forms. When you create new forms, you gain new ideas, emotions, and concepts that never existed before.

Art is the most human thing possible. When I was a student, there was a big conflict between form and content. One position was that content is not very interesting, and what’s really important is the form. On the other hand, people that just were interested in content couldn’t make reasonable drawings, paintings, or sculpture. Everything is a composite of both form and content.

h: If you had to describe the future in three words, what would they be?

TC: A lot of words I could do, but not three.

h: That’s okay too. It was a big ask.

TC: Okay, then I’d say: A future is possible, but we have to think and behave differently.

All Shook Up, 2025; Bronze; 226 x 151 x 118 cm; 89 x 59 1/2 x 46 1/2 in

© TONY CRAGG, Courtesy of LISSON GALLERY

Untitled, 2025; Bronze; 177 x 109 x 66 cm; 69 5/8 x 42 7/8 x 26 in

© TONY CRAGG, Courtesy of LISSON GALLERY

Words: JULIA SILVERBERG