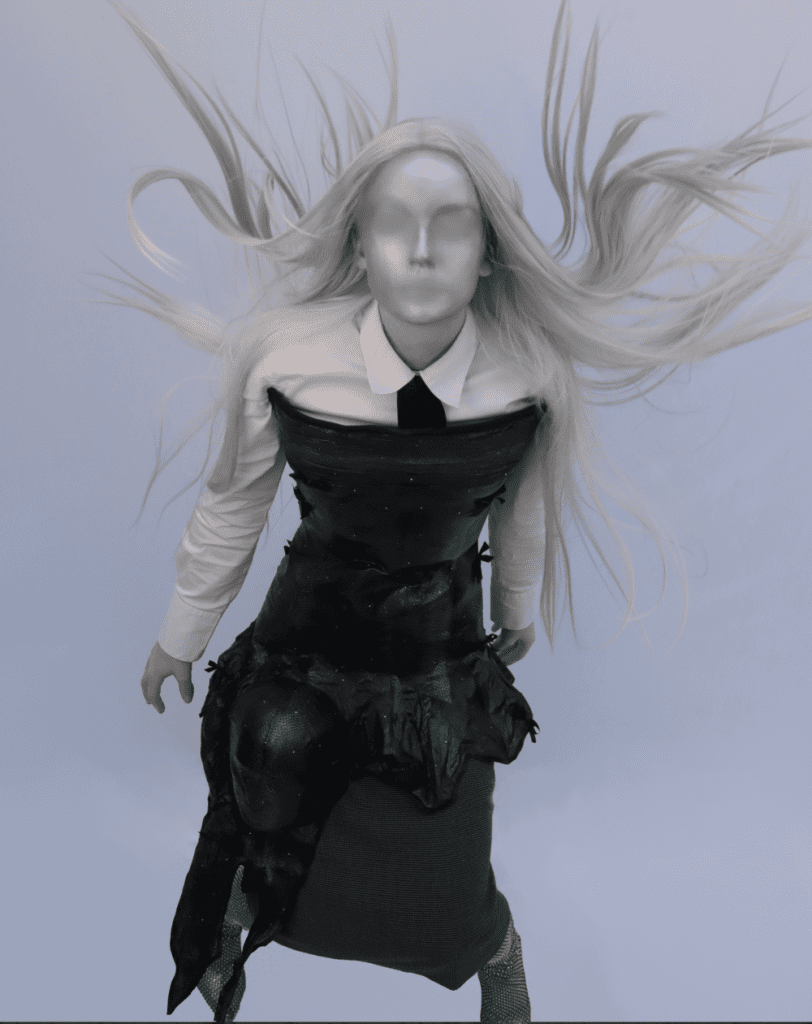

Isabelle Taylor, a pioneer in crafting embezzling garments from fish leather, is a young artist who combines environmental consciousness and artistic innovation in her pieces. From the depths of the ocean to the forefront of design, Isabelle’s creations not only captivate the eye but also echo a resounding call for more sustainable practices in fashion.

hube: Your garments seem to draw inspiration from the depths of the ocean. Could you share the moment or experience that initially inspired you to utilise fish skins in your art, and how has this connection with marine life and environmental consciousness influenced your creative process?

Isabelle Taylor: I had previously seen a few designers use fish leather in garments but I was still fascinated by how few people were exploring it as a textile for fashion and so I had to try it for myself to see why. I fell in love with the texture immediately and I love how it’s not only making really good use of waste, but it’s biodegradable, meaning I could pursue my love for fashion whilst feeling guilt-free about polluting the planet. I’m still confused as to why so few people are exploring it. After some experimenting, I realised my interest lay in sculpting the skins into garments, as opposed to making individual leather pieces to sew together. Seeing fish swimming in the ocean is one of my favourite things— the way their skin sparkles in the sunlight is incredibly beautiful. I try to capture the essence of this in my work — by adding subtle (high-quality) rhinestones to the surface of my garments to give them the same element of sparkle as they would have in the wild.

h: Fish skins bring a distinctive texture to your creations. How do you manipulate and sculpt this unconventional material to achieve the desired tactile and visual effects in your pieces?

IT: I drape the skins flat onto a mould. The mould is made from anything I can find like, for example, an old tablecloth I used to make a voluminous skirt. If I want something more organic that resembles creased fabric, I’ll drape the skins with more folds and creases. Alternatively, I use pegs or sew thread through the skins to pin them into surreal shapes. Once the skins have dried I can take them off the mould and have a garment entirely made from fish leather.

h: In an industry often criticised for its environmental impact, your use of fish skins is commendably sustainable. It is definitely a new and unique approach to fashion. How do you see your work contributing to a more eco-conscious approach in the world of art? What are you aspiring to invoke in others with such choices?

IT: I’m trying to introduce a new method of construction into fashion, to show that structures in garments that are usually made from plastics can be made from biodegradable materials instead. Not only that but also to be reducing waste in a different industry altogether — the seafood industry. I’m trying to show others that we can work together, cross-disciplinary, to benefit both parties instead of looking for the answers just within fashion. I also want people to be more open to change because that’s what we need. We need a radical change in the fashion industry; therefore, we need to expect to see something radically different. This is what my work resembles. People have mixed emotions about my work because it makes them uncomfortable to observe something they’ve never seen before. But I’m excited by it because it starts a conversation.

h: Could you give us a glimpse into the evolution of your artistic style and the specific innovations we can expect in these new pieces? Was there a moment during the creation of your latest pieces that required a particularly intricate or time-consuming technique?

IT: I’m currently working on improving my leather textile as opposed to new shapes because I need to prioritise that before anything else. It will take more experimentation, research, and critical analysis of my previous work. However, I plan to continue to explore surrealism in my work and to create sculptural pieces that both complement the shape of the human body and morph into shapes which are entirely separate from it — something more architectural or organic. Each stage of my process is equally time-consuming so I also need to work towards techniques that can help me cut back the production time!

h: How are your new garments different from the previous models? What do you think changed in your artistic practice and what stayed the same?

IT: I concentrated on improving the strength, finish, colour richness, and longevity of the garment for my latest model and I’m happy that I have successfully achieved all those things. However, it still needs improving before I’m happy to sell anything as I want the product to be of high quality. I also am concentrating on utilising more interesting, practical, and vintage fastenings. The draping method in which I constructed the latest garment remains the same as the first model though.