For Olivier Saillard, the history of fashion is more than a subject of research, it is a constant source of inspiration and curiosity. Combining an extensive knowledge of fashion with a fascination for the intimate relationship we develop with clothes, he brings a new perspective to the industry through his work as the Director of Fondation Azzedine Alaïa; through the exhibitions he curates, amongst them, Yohji Yamamoto just clothes and Balenciaga, l’œuvre au noir; and through his performance art fashion work. With his long-time collaborator Tilda Swinton, he explores the “poetic vocation of performance” through the archives of fashion museums, couture-level craftsmanship, and sartorial worlds.

In this interview, Olivier Saillard shares his personal and poetic approach to fashion history, blending past and present in innovative curatorial work.

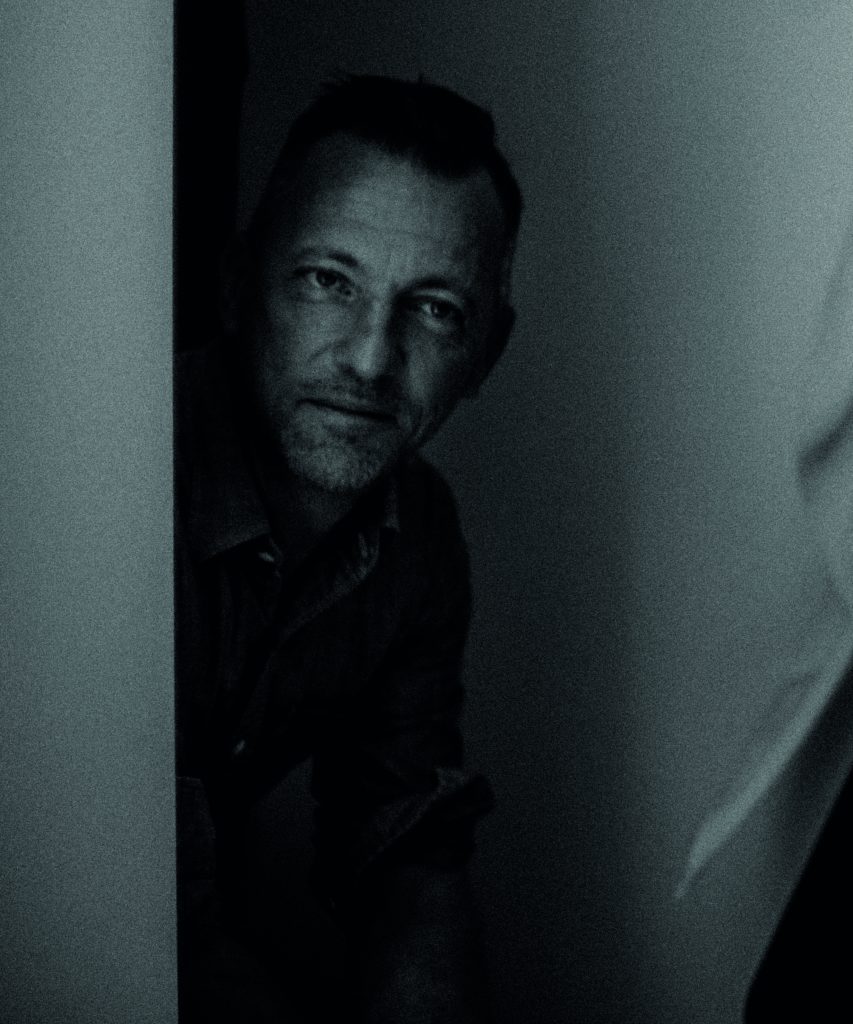

Photography by RUEDIGER GLATZ

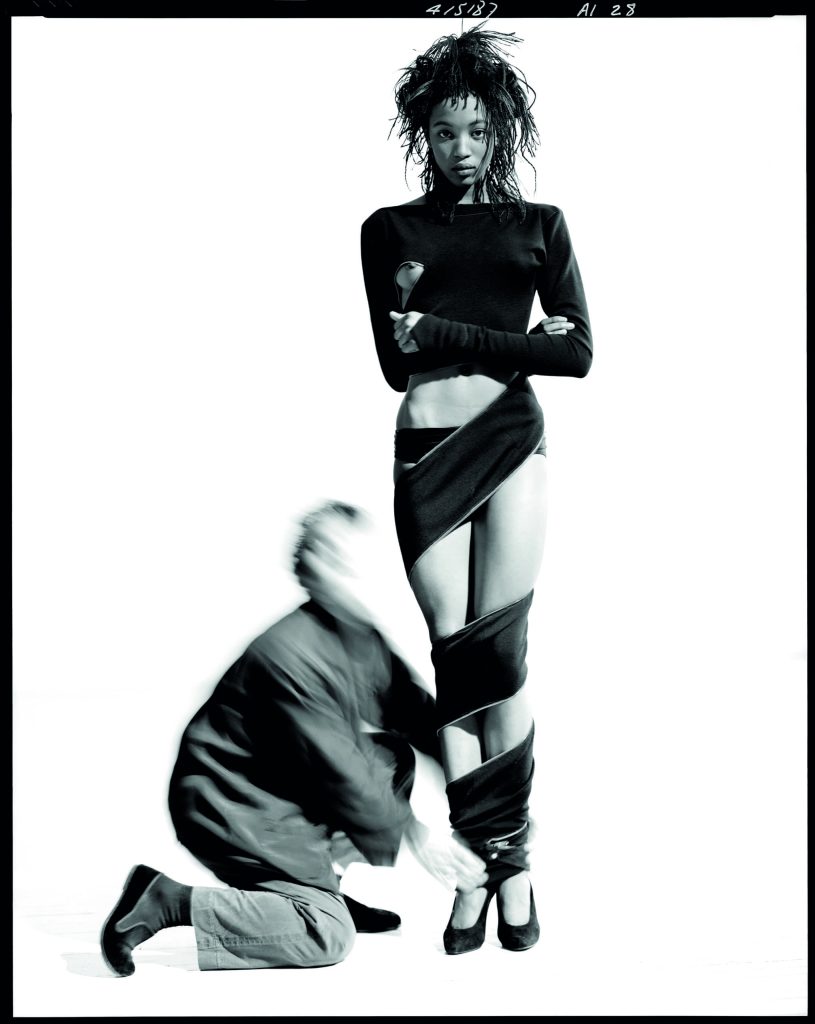

Photography by ARTHUR ELGORT

Courtesy of FONDATION AZZEDINE ALAÏA

hube: Harmony, inspiration, joy, worship, indifference, reconciliation. Each of us chooses our own way of interacting with and interpreting the artistic universe. Being inside this universe, you instead choose ways of interacting and interpreting the real world. Could you tell us a little about this?

Olivier Saillard: It’s difficult. I understand the sense of it, but as a person who has always worked in fashion, I don’t feel part of the real world. I’m not that interested in the present, I’m interested in the past. There is a gap between the real world and the world from the past that I definitely feel I belong more to. If I consider my work as a historian, an artistic director, a poet, or a performer, I think I’m trying to offer an analysis of the world through a poetic glance.

I don’t think things are worse than 30 years ago when I started, but I still believe we can invent a better world. I believe there are very poetic things in this world, different artistic lands. I believe in the power of the poet and the artist to define it this way. I’m quite afraid about the real world, especially with the rise of social media.

When I started as a curator and a performer I tried to invent my own world. It wasn’t very easy for a curator to do something so “alive.” But it was very fundamental and very necessary for me to invent something which would provide another way of presenting the history of fashion and gesture.

h: We believe that the history of fashion is not just a subject of research for you, but also a great source of inspiration. It also seems to us that your exhibitions and performances are deeply personal statements. Your curatorial work connects the viewer and the artist in a very intimate way. In your artistic practice you choose the angles and accents, creating a completely new narrative. Could you tell us about the ideas, subjects, and characters that you find inspiring at the moment?

OS: I started late in the ’80s, I did 250 exhibitions and in the middle of my career I was quite exhausted. My job was very interesting but also frustrating. I was trying to find new ways to analyse and share the history of fashion and not just through exhibitions only. It was mostly about reintroducing movement, souvenirs, memories, and models, to explain the history of fashion.

Let me tell you a story as an example: one day I was in Bologna, Italy. I visited a museum devoted to musical instruments. Something struck me, they were all showcased behind glass, as if they were in a museum of antiquities. It felt weird to see beautiful old guitars and clavecins [harpsichords] without any sound. When we left the museum, we came across a conservatory with music coming from the window. I told Gael, my partner: “You know what, I’ve been wrong for 20 years!” I always did exhibitions without sound, that is what was lacking. At that moment, fashion performances were invented, in order to give sound to history.

I have always felt very comfortable as an historian, but I didn’t feel that comfortable doing exhibitions with only costumes and nothing else. It was 20 years ago that I told my partner we had to do something else. Diana Vreeland and Nadine Gasc, who was a famous curator in Paris, did an excellent job in the ’70s, but it was up to us to innovate and invent a new way to explain fashion, to explain clothes.

I’m not a huge fan of the word fashion, by the way. The word clothes resonates more with me. The word clothes has a huge history. For example, I’d love to ask you why you chose that sweater today, how long you have had it for. I’m more interested in the relationship with clothes that anybody can identify with than I am in fashion. This doesn’t change the fact that I’ve been very inspired by fashion designers like Yohji Yamamoto, Azzedine Alaïa, and Martin Margiela, but I’m also very interested in the very intimate relationship we all have with our own wardrobe.

h: You have collaborated with some of the greatest couturiers in the world, what did you learn from such experiences?

OS: I was very passionate when I started as curator. I started as the Director of Musée de la Mode in Marseille. I was 27 years old, probably the youngest curator at this time. It wasn’t very easy, but it was very exciting. I was very happy at this time as fashion museums were far from the idea of contemporary fashion.

I had one idea, one wish: to invite contemporary fashion designers to the museum. They were all very afraid! I remember asking Jean Paul Gaultier to participate in a solo exhibition, he refused. Yohji Yamamoto refused as well. For them, being exhibited in a museum was like being dead. I had to push by drawing a comparison between fashion and contemporary art museums. In contemporary art, most artists are very comfortable being the subject of an exhibition. Being exhibited at the MoMA is actually the opposite of being dead.