Scarf ISSEY MIYAKE

Balaclava MELITTA BAUMEISTER

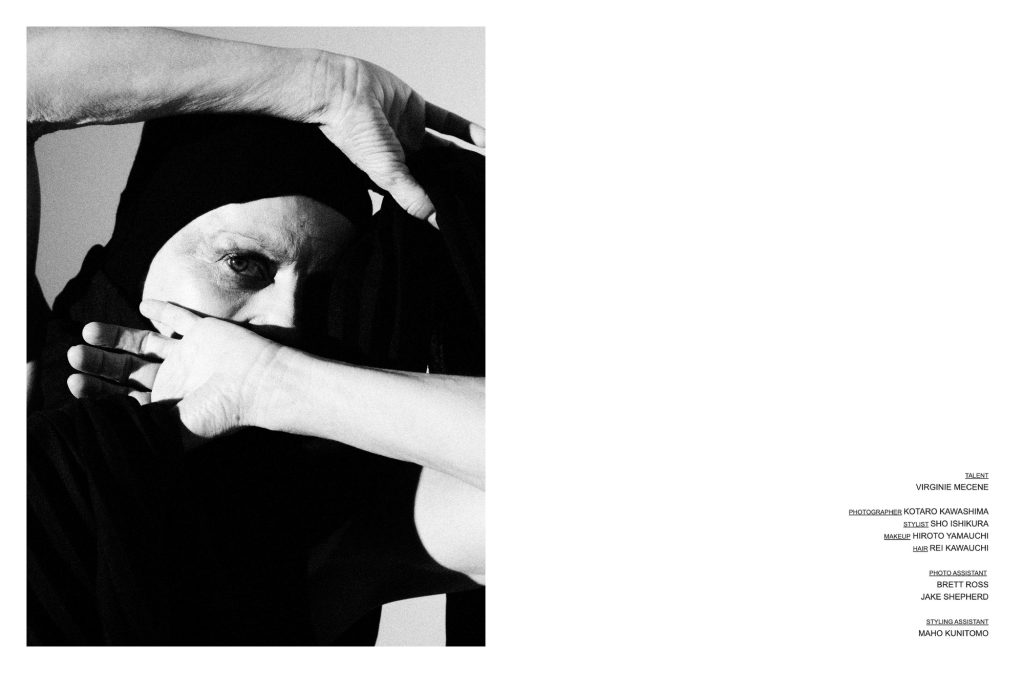

Virginie Mécène’s journey with the Martha Graham Dance Company is a testament to her dedication and passion for dance. With a career that spans decades, she has played pivotal roles as a dancer, choreographer, and educator, contributing significantly to the preservation and evolution of Graham’s legacy. Recently, her impact was highlighted in our new story, captured by photographer Kotaro Kawashima and styled by Sho Ishikura, further showcasing her enduring influence in the world of dance.

hube: Your journey with the Martha Graham Dance Company has been extensive. Can you share a pivotal moment that significantly shaped your career as a dancer and choreographer?

Virginie Mécène: I am not sure I had one specific pivotal point in my career, but certain times shaped it in different ways. The first was when I joined the Martha Graham Dance Company in 1994. This definitely validated the direction of my dance career. In the mid-nineties, I was dancing with two different dance companies simultaneously, resulting in an explosion of creativity. Not only was I learning and dancing historic roles in one, but I was also creating new roles in the other. I was dancing with the Martha Graham Dance Company in the afternoon and then with the Buglisi Dance Theatre (at the time called Buglisi/Foreman Dance) in the evening. I remember wearing an oversized jumper that I would put on over my dance clothes to go from one studio to the other, taking the New York City subway from downtown to uptown to jump from one rehearsal to the next. I was touring with both companies, so it was a hectic and demanding time but wonderfully creative. This is the dream of a dancer – to be in demand, and when you are young and eager to dance, the energy keeps renewing.

I was deeply involved with this community of dancers and choreographers, strengthening and magnifying my commitment to this artistic form. In 2000, when the Martha Graham Dance Company suspended all activities due to an internal lawsuit, I was cut off from my dance floor. During that time, I enrolled in acting and singing classes, which enhanced my dancing skills. I also picked up work with another dance company, the Battery Dance Company, with which I travelled extensively to India and around the Baltic Sea. This company was smaller and was performing in smaller venues, allowing for a more direct connection with the community. This enriching cultural experience allowed me to meet and interact with people close to their traditions. We danced on stages of all shapes and sizes, and this experience gave me a different view of the purpose of performing and its impact on the community. Meanwhile, the Martha Graham Dance Company resumed all activities after two years, and I was juggling three different dance companies. I travelled with the three companies all around the globe.

As a choreographer, my work was being put on hold as I was swamped dancing, but as soon as the opportunity arose, I continued to create. When I left the Martha Graham Dance Company in 2006, I became the Director of the Martha Graham School and the Artistic Director of Martha Graham’s second company, Graham 2, and I started choreographing again for the dancers.